- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Art of the pitcher

#Shortstops: Art of the pitcher

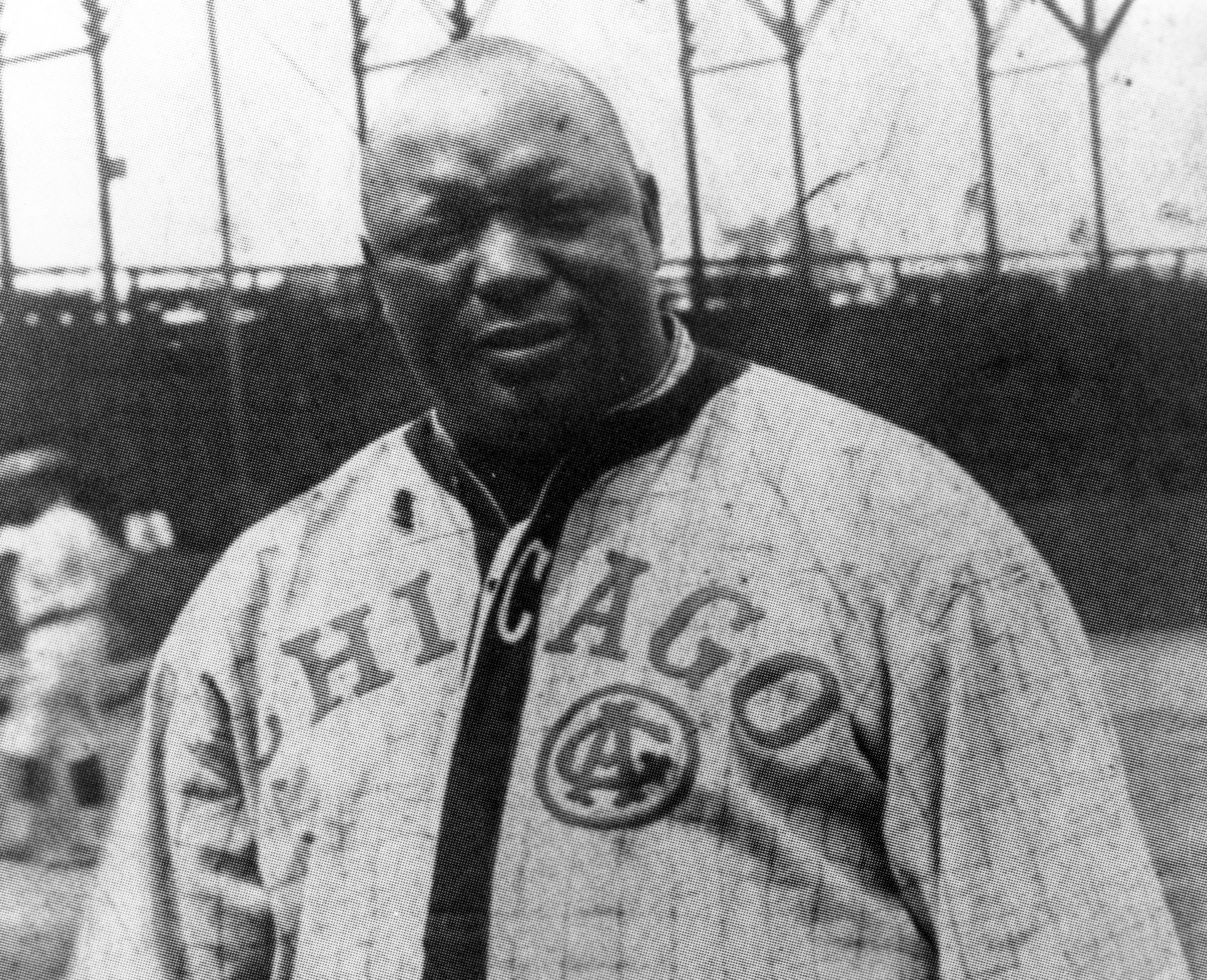

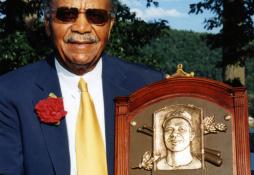

In the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Steele Art Gallery hangs Deryl Daniel Mackie's astonishing, 73 1/8” by 62 3/4" portrait of “Smokey Joe Williams''” from 1985. This imposing, life-sized composition includes the highly stylized and colorful markings of Mackie’s brushwork.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Mackie was known for his small-scale stylized portraitures of musicians, chefs, laborers and dancers, not of sports figures, so it's unknown why he chose to paint Williams. This portrait calls the viewer’s attention to Williams's physique and his legendary career as an athlete who made major strides for Black baseball players.

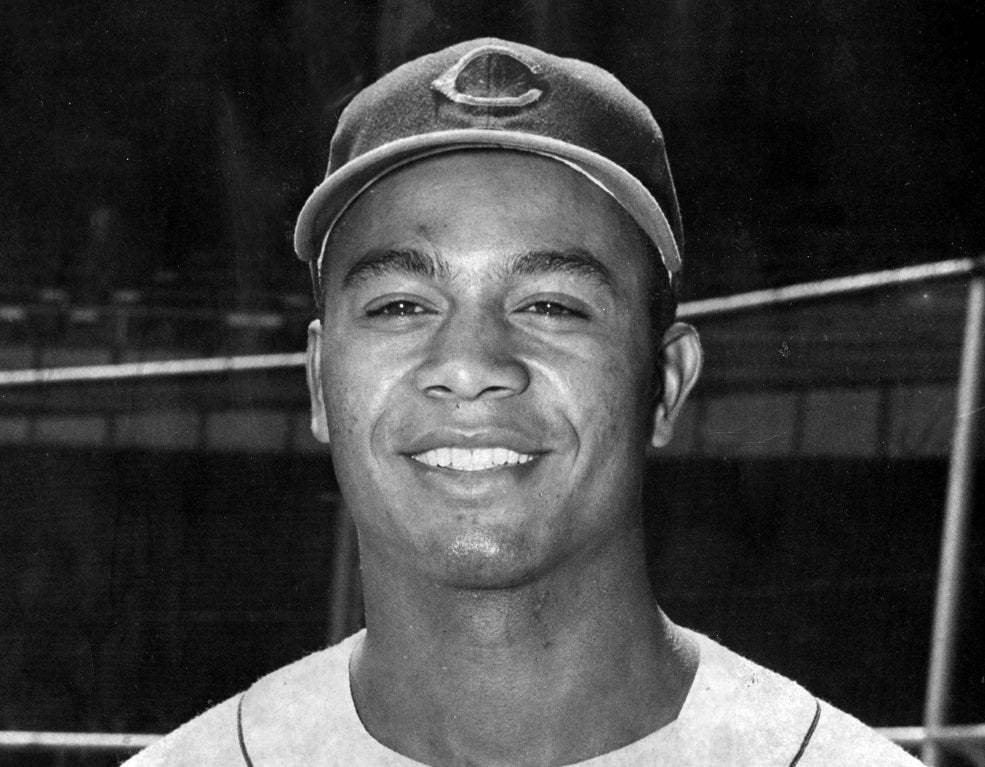

Williams was born in Seguin, Texas in the late 1880s and had Black as well as Comanche Indian ancestors. He was known for his fastball, which earned him the nicknames “Cyclone” and “Smokey Joe.” In his 27-year pitching career from 1905 to 1932, some sources attribute him with 125 wins and 56 losses, while others suggest a 107-57 record. Some state he played in a total of 111 games, including 104 complete games and seven shutouts.

Most sources agree, however, that Williams had nine wins (including four shutouts), two losses and one tie against white major league teams.

As a Black player in that era, he was never given a chance to play in the (white) major leagues, but Ty Cobb considered Williams a “sure 30-game winner” if he had ever been given the chance.

Williams faced extreme oppression and segregation. In 1950, a year before he passed away and three years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, Williams stated, “The important thing is that the long fight against the ban has been lifted. I just praise the Lord I’ve lived to see the day.”

Bill James ranked Williams, a 1999 Hall of Fame inductee, as the 12th greatest pitcher in baseball history, just behind Sandy Koufax and just ahead of Bob Feller.

Born in 1949, Deryl Daniel Mackie grew up in Philadelphia, Pa. and studied at Temple’s Tyler School of Fine Arts. He worked as a curator for Philadelphia’s Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum and was a founding member of the Painted Bride Art Center, which served as a venue for emerging visual and performing arts in the greater Philadelphia region. Mackie was an accomplished artist within the gay community, with his work appearing in New Gay Life, as well as on the cover of “In the Life.” Mackie died of complications from AIDS in 2007 at the age of 58.

Art, literature, music and even legendary sports moments can live on past their creator and affect people for centuries to come. No one may ever know precisely why Mackie painted Williams, but collectively, Williams and Mackie remind us that baseball is a sport which touches all communities and can spark important conversations regarding inclusivity.

Emma Haring is a 2023 public programming intern in the Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Leadership Development