- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1998 Topps Brian Jordan

#CardCorner: 1998 Topps Brian Jordan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Over its first 45 years of producing baseball cards, the Topps Company almost exclusively photographed players and managers at the ballpark, either in big league cities or at Spring Training sites. The ballpark, of course, has its limits; there are a finite number of places to take photographs at a typical stadium. Foul territory often provides the site for posed shots. Then there’s the batting cage, the dugout, or the bullpen. Action shots, which involve players in the actual field of play, can be snapped from the camera wells beyond the dugouts. Or a baseball card photographer can pose a player in the stands, at least when there are no fans in the ballpark.

By the 1990s, Topps decided to do something a bit creative with its cards. The 1991 set saw Topps introduce photos taken from unusual angles. For example, a memorable photo of Benito Santiago is taken from directly above home plate and shows him staring into the camera, as if he is trying to track a pop up. The card of Roger Clemens shows him leaning against the Fenway Park scoreboard, with the words “STRIKE OUT” fully evident behind him.

In 1998, Topps took creativity to another level. Rather than rely solely on the ambiance of Spring Training and the various major league ballparks, the artistic folks at Topps began to experiment with doing some of their photography inside of a studio, or other indoor locations, while using offbeat props. Topps included several cards that had been snapped in studio locations, including one for a young Bobby Abreu and another for veteran closer Jeff Montgomery, the latter holding a fire extinguisher.

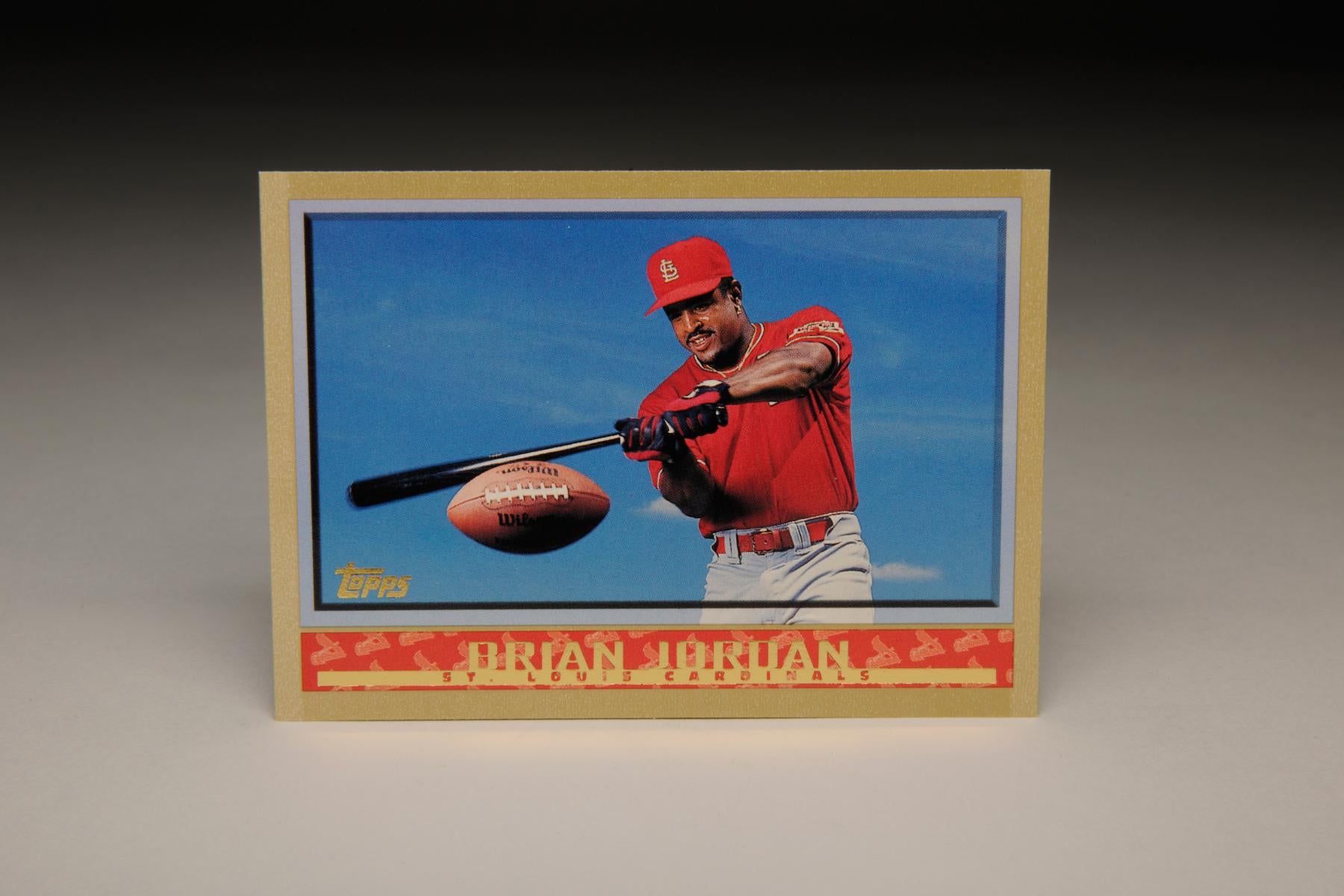

Perhaps the most effective example of studio background can be found in Brian Jordan’s card. In order to maximize the effectiveness of the photo, Topps uses a landscape arrangement for the card, instead of the usual portrait layout. Set against a studio backdrop featuring a bright blue sky, Jordan is seen taking a practice swing, not at a baseball, but at a football. We can only assume that the football is suspended from an imperceptibly thin piece of wire. This was not the first time that a baseball card displayed a football; Nolan Ryan can be seen throwing one on his 1989 Upper Deck card. But it was the first card in which a player can be seen taking a bat to the football. In this case, the reference is clear: At one time, Jordan starred as a Pro Bowl safety for the National Football League’s Atlanta Falcons.

By the time that Topps issued his 1998 card, the burly, well-built Jordan had voluntarily ended his NFL career, but the connection to the gridiron game remained pertinent. After starring for the Falcons from 1989 to 1991, Jordan decided to quit football and concentrate his efforts on playing baseball. Perhaps there is something symbolic about the Topps card, with Jordan figuratively swatting away his football career with the help of the baseball bat.

It was the kind of career move that Jordan’s friend, Deion Sanders, had never been willing to make, but it made Jordan the better guy from this biased baseball fan’s perspective. Jordan was willing to make the full commitment to one sport - and one team. Meanwhile, Sanders was splitting time between the Falcons and Atlanta Braves, even missing parts of important playoff games with the Braves in 1992 because of his desire to be a two-sport star. That desire drew the criticism of CBS broadcaster Tim McCarver, who called Sanders onto the carpet for his failure to commit fully to the Braves’ postseason run. Sanders responded by dumping three buckets of ice water onto McCarver in the Atlanta clubhouse.

Although Sanders was a more dominant football player (a Pro Football Hall of Famer, in fact), Jordan was by far the better baseball player. That’s not to say that Sanders lacked baseball talent - he had incredible footspeed and a lightning quick bat - but he also had weaknesses in his game. He hit with little power, showed virtually no patience to draw walks and struggled with a poor throwing arm from the outfield. He also showed little willingness to put in the kind of time commitment that is needed to develop one’s baseball skills. By comparison, Jordan had a stronger baseball work ethic, much more power and a more potent throwing arm. He played seven seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals, emerging as a solid right fielder and offensive contributor.

Jordan’s baseball odyssey began in 1988 when the Cardinals made him their first pick in the amateur draft and assigned him to Hamilton, Ontario, of the New York-Penn League. Slowly working his way through the Redbirds’ farm system, Jordan showed little power but hit for high averages and displayed range and athleticism in the outfield.

By 1992, Jordan made it to St. Louis, though he hit only .207 in 55 games. He showed more promise the next two seasons, and finally moved into the Cardinals’ starting lineup in 1995. With 22 home runs and 24 stolen bases, Jordan gave the Cardinals a double dose of speed and power, while filling out a terrific young outfield that also included Bernard Gilkey and Ray Lankford. All that Jordan really lacked was patience at the plate; he drew only 22 walks in 131 games.

Jordan put together his finest season in 1998, the year that this card was issued to the public. He achieved a career-high OPS of .902, hit 25 home runs, stole 17 bases, and increased his walk total to 40. His defensive play in right field bordered on the spectacular, as he used his skills as a safety in football to chase down fly balls. With that season serving as a springboard, Jordan cashed in on free agency. The New York Yankees, among other teams, pursued him aggressively, but Jordan opted for a five-year, $35 million deal with the Braves. The contract not only made Jordan a rich man, but it gave him a chance to play for the same franchise as his idol, Hank Aaron.

Jordan soon found himself taking on an unexpectedly greater role with the Braves. When a diagnosis of cancer left Atlanta without cleanup man Andres Galarraga, Jordan stepped into the lineup breach, reached the century mark in both RBI and runs scored, and slugged a respectable .465. At midseason, Jordan earned selection to the National League’s All-Star team.

Jordan saved some of his finest play for that postseason. Playing in the 1999 Division Series against the Houston Astros, Jordan batted .471 and collected seven RBI, accounting for more than one-third of Atlanta’s run total for the series. Jordan then hit two home runs against the New York Mets in the Championship Series before slumping in his first and only World Series appearance.

Remaining with the Braves through the 2001 season, Jordan continued to play well in Atlanta. He posted an impressive OPS of .830 and received some MVP votes in 2001, but the Braves saw a chance to acquire a superstar who was available in a trade. So in January of 2002, the Braves sent Jordan and left-handed pitcher Odalis Perez to the Los Angeles Dodgers for All-Star outfielder Gary Sheffield.

Jordan played productively in his first season with Los Angeles, hitting .285 with 18 home runs, but injuries began to cut into his effectiveness the following summer. That winter, Jordan became a free agent and signed a one-year contract with the Texas Rangers. During Spring Training, he made an immediate impression on his new manager, Buck Showalter. “You can tell already the weight that Brian’s words carry,” Showalter told the Associated Press. “What I love about him, he’s very selective about when he uses [those words]… The other day when he spoke up, every head there jerked around to see what he had to say.”

Unfortunately, a series of injuries once again stifled Jordan’s on-field performance, limiting him to 61 games with the Rangers and a meager .222 batting average. The Rangers opted not to re-sign him. So he returned to the Braves, putting in time as a part-time corner outfielder and backup first baseman for two seasons before retiring at the end of 2006.

So what is Brian Jordan’s legacy? His pro football career spanned only two-and-a-half years, so there’s no way that he will be remembered in the same way as a Sanders or a Bo Jackson. His legacy must be found in baseball, where he lasted longer than either Sanders or the man who spurred the “Bo Knows” campaign. Injuries prevented Jordan from becoming a great player, but he was still a good one. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

But Jordan’s talents don’t stop with his athletic feats. Even in retirement, he remains active. He now writes children’s books, where he emphasizes themes like teamwork and his dislike of bullying.

It seems there isn’t much that Brian Jordan can’t do.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

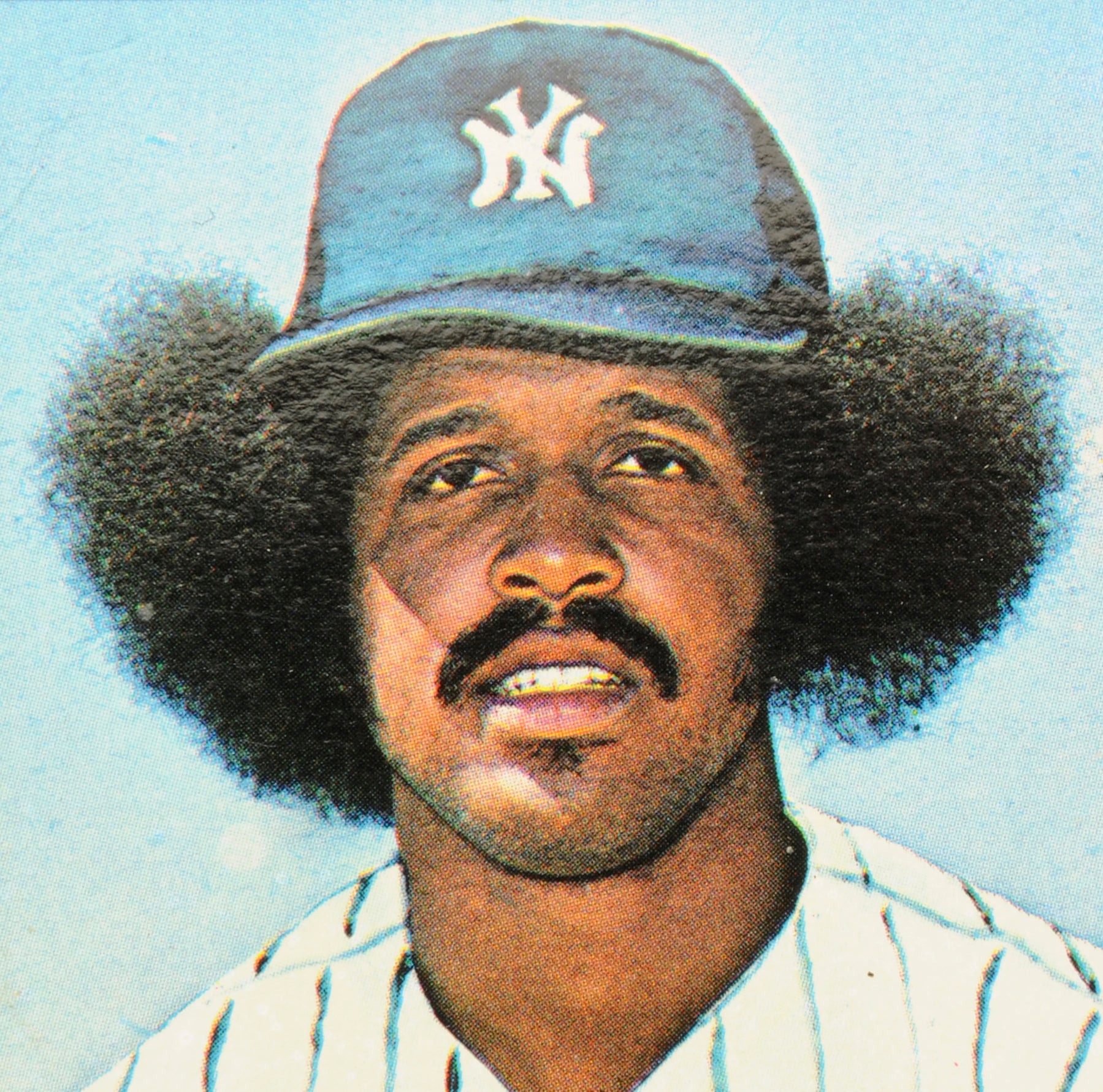

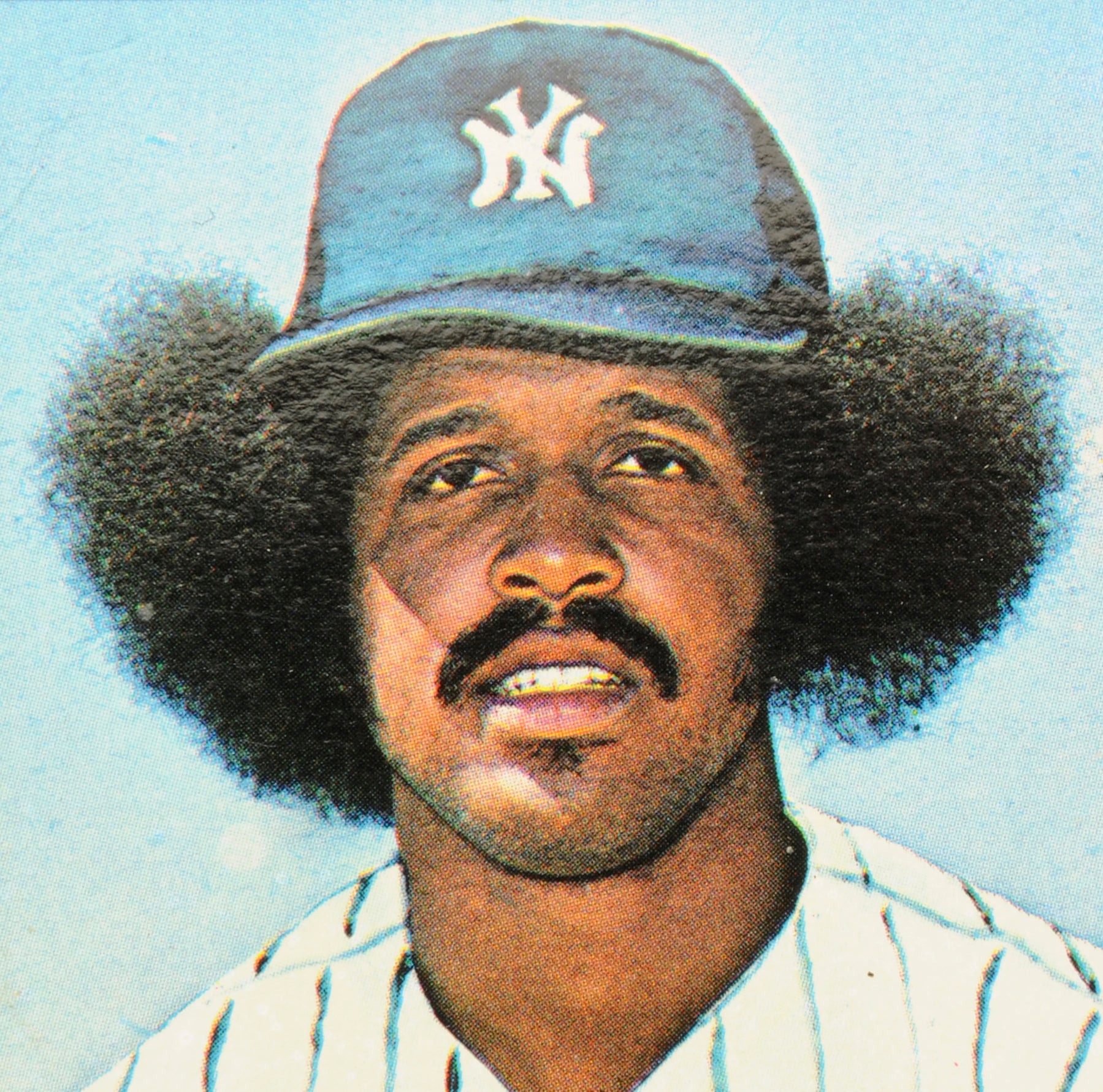

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

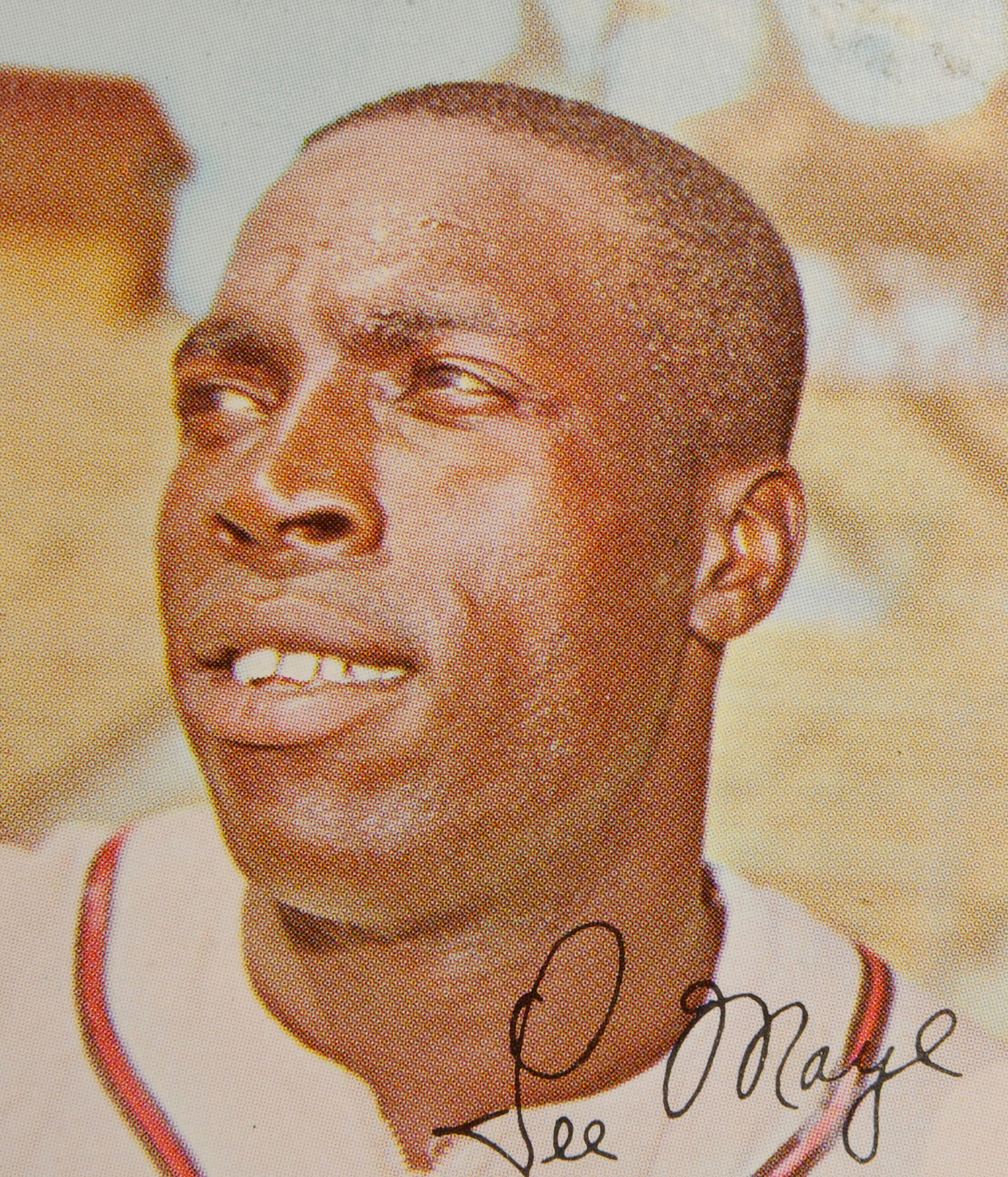

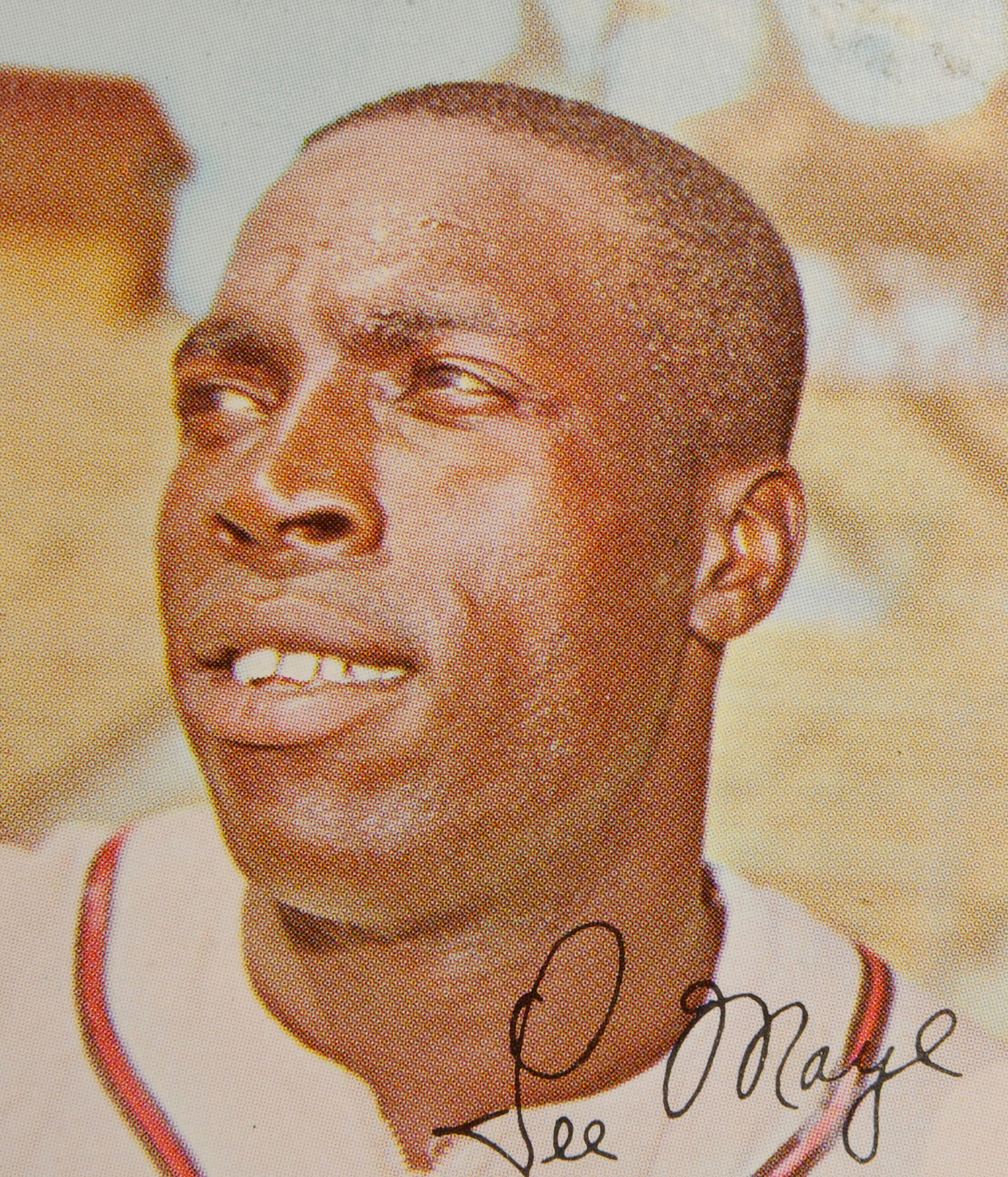

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Steele Interns experience MiLB excellence with ValleyCats

The Voice of Babe Ruth

A Classic to Remember

The Ultimate Loving Cups

#CardCorner: 2015 Topps Mike Trout

Chip off the Block

Opening Day, the Baseball Holiday

Class of 2015 Humbled, Honored at Sunday’s Hall of Fame Induction

Griffey, Piazza reflect the day before induction

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr_1972_08_14a

01.01.2023

Fan Favorite Ozzie Smith Hosts 14th Edition of Hall of Fame Weekend Tradition PLAY Ball

01.01.2023

Pastime Presents: Museum’s 75th Anniversary Offers Fans Unique Gift Opportunities

01.01.2023