- Home

- Our Stories

- Recalling Roberto

Recalling Roberto

Even a diehard fan would struggle in coming up with the name of the pitcher who gave up Willie Mays’ 3000th hit. (It was a right-hander named Mike Wegener, who was pitching for the Montreal Expos.) Similarly, most fans probably don’t remember the identity of the pitcher who surrendered Hank Aaron’s 3,000th. (It was Wayne Simpson, a onetime phenom with the Cincinnati Reds who soon ran into arm problems, short-circuiting his promising career.)

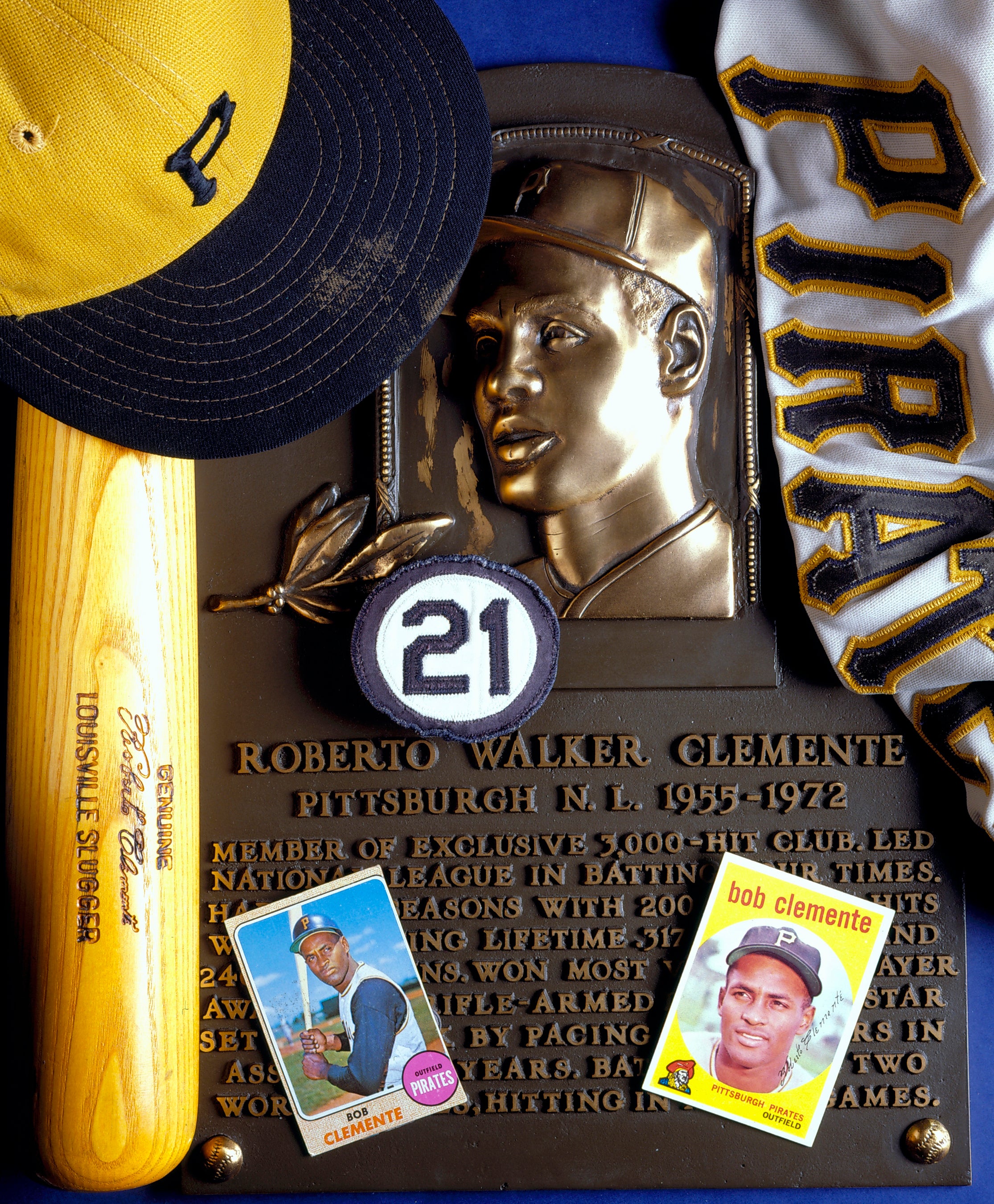

In the case of Roberto Clemente’s 3,000th hit, the man who would become linked with the Hall of Famer’s milestone is far better known than Wegener or Simpson. His name is Jonathan Trumpbour Matlack, better known as Jon Matlack, a pitcher who developed his own identity and reputation during the 1970s. A Rookie of the Year Award, three All-Star Game selections, and an All-Star Game MVP will make you memorable, particularly to fans of the New York Mets.

Now 65 and at least momentarily retired from baseball, Matlack visited the Hall of Fame in September to take part in a special program titled “Ya’ Gotta Believe.” Speaking in front of an enthusiastic crowd of loyal Clemente supporters and rabid Mets fans, a thoughtful Matlack discussed his own career, the fortunes of the surprising 1973 Mets, the influence of managers Gil Hodges and Yogi Berra, and the circumstances surrounding the milestone hit collected by Clemente 43 years ago.

At home in Pennsylvania

Growing up in Pennsylvania and attending Henderson High School in the 1960s, Matlack already had some familiarity with Clemente, who was well known to fans throughout the state. As a youngster, Matlack did not see Clemente play in person at Forbes Field, but that would change after the left-hander turned professional.

“I didn’t see him play before I was drafted, but coincidentally I went to the University of Pittsburgh,” said the well-spoken Matlack, speaking in front of a crowd of 170 fans in the Grandstand Theater. “After I was signed [in 1967], I saw him play at Forbes Field. This was after I had signed with the Mets. He was just a phenomenal ballplayer. He had all the tools that you could want.”

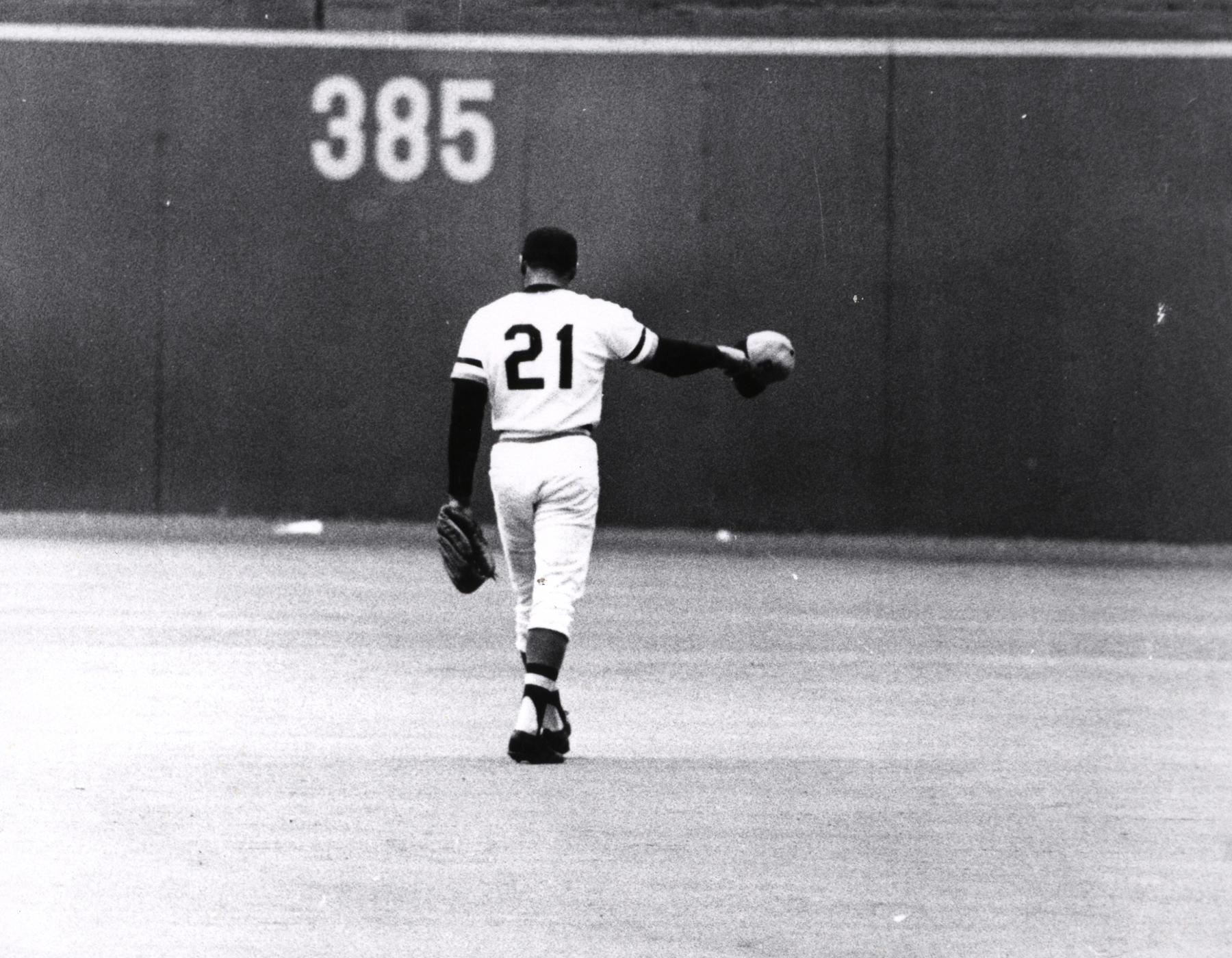

Even by his final season in 1972, those tools had not faded. Clemente could still run, hit, and hit with power, and remained a strong defensive presence in right field. He hit .312, posted an OPS of .835, and won his 12th Gold Glove Award. Perhaps the only skill that Clemente had lost was his ability to play every day; due to a variety of nagging injuries, Clemente appeared in only 102 games that season.

Yet, Clemente played enough to draw within range of his 3,000th hit. With the regular season coming to a close and the Pittsburgh Pirates playing in their 152nd game (out of a total of 154 during the strike-shortened season), Clemente stood just one hit short. After striking out badly in his first at-bat against Matlack, Clemente came to bat in the bottom of the fourth inning at Three Rivers Stadium.

Matlack recalls the pitch that resulted in No. 3,000.

“I don’t specifically remember the sequence of pitches,” Matlack said. “But I do remember the pitch that he hit. When it left my hand, it was a breaking ball, and I was trying to throw the ball low and away toward the outside corner. It was going to be outside. I thought it was going to be called a little ball. And I was a little disappointed that he was able to hit it and it ended up being a double.”

As the ball was retrieved and returned to the Pirates’ dugout, Clemente doffed his helmet to the smallish crowd of just over 13,000 fans. At first, Matlack did not understand the reason for the gesture or the retrieval of the ball. “I had no idea that it was his 3,000th hit. None,” Matlack told a near capacity crowd of 170 fans in the Hall of Fame’s Grandstand Theater in September. “He hit a ball into left field for a double and then was standing at second base, tipping his helmet to the crowd. I had no idea until I looked up and saw it flashing on the scoreboard that he had just hit his 3,000th hit.”

A moment in history

In stark contrast to today’s game, in which milestone moments are often marked by game-stopping ceremonies, there was less attention paid to a 3,000th hit in 1972. Yes, it was noted and discussed, but without the same fervor attached to similar moments in the modern day. As such, Matlack and other members of the Mets were oblivious to the achievement – at least initially.

Once Matlack understood that history had been made by Clemente, he realized that he had more work to do.

There was not a whole lot of thought other than, ‘It has happened.’ I’m going to be in the history books somewhere for allowing hit No. 3,000.”

On another level, none of the players knew that Clemente would never again register a hit in regular season play, due to the tragic circumstances that would befall him that winter.

“At that point we didn’t know that was going to be his last hit,” said Matlack, “so that makes it a little bit more poignant. But I was a rookie, losing a ballgame at the tail-end of the season, doing my best to get through the game. That hit was just what it was, a double, and I had to go on to the next hitter and try to figure out how to get him out.”

Matlack felt that he had made a good pitch to Clemente, low and outside, but as with many offerings delivered to the Pirates great, he found a way to convert it into a line drive.

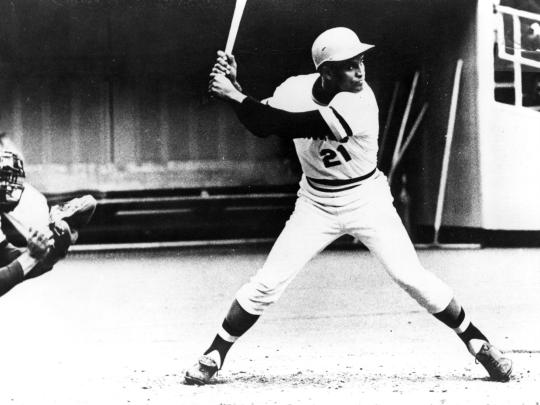

“I think the key to his his success as a hitter was this: his hands never committed [until the last moment],” said Matlack. “He would take a big stride, but his hands always stayed back, in a cocked position. He would keep his hands back. His timing was such that he was still able to get to the pitch.

“Being a bad ball hitter, a good pitch down in the zone off the plate was probably the best way to go. You’d hope he would hit a ground ball to short, a ground ball to second, something like that. A mistake with an off-speed pitch where he’s have a chance to adjust, keep his hands back, see the ball and realize that he could get to it, was a pitch that he was more apt to hit. Make quality pitches down in the zone and stay ahead in the count was the best rule of thumb with Clemente.”

When asked if a pitcher might be advised to throw Clemente an inside fastball as a way of intimidating him, Matlack offered a quick response, followed by a laugh. “Backing him off the plate with a fastball was one of the things you didn’t want to do with him. That might make his focus just that more sharp. There were a few guys in the league that obviously you could intimidate with inside pitches. But he was not one of them.”

Tragedy at sea

Clemente’s death that New Year’s Eve, as part of a mission of mercy to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua 43 years ago, prevented him from ever facing Matlack again. The two men never talked at the ballpark, either at Three Rivers Stadium or at Shea Stadium, but Matlack did meet Clemente under far more social (and special) circumstances.

“I did have a chance to talk to him when I played winter ball the winter before [the 3,000th hit], when I went down to winter ball in San Juan.” Matlack recalled. “He invited the American players over to his home for a meal and some conversation. It was quite a lot of fun. He seemed like an extremely nice, very personable kind of guy.”

After dinner, Matlack and the other players congregated in Clemente’s trophy room, where “The Great One” held court with some of his guests. That led to a memorable discovery for Matlack.

“I was just in awe, being there with him [and his family]. We went into his trophy room, if you will, which was unbelievable,” Matlack said. “The thing that impressed me most was when he was talking to a couple of hitters, it had something to do with hitting. It was not something I was particularly interested in. So I was looking at the stuff on his wall, listening only half-heartedly.

“He picked up a maximum dimension bat that he had in the corner. He was showing the guys what he was talking about. I don’t know if anybody knows what a maximum dimension bat is, but it’s the biggest bat that you’re legally allowed to take to home plate. It’s about the size of a grapefruit [at the barrel]. It is monstrous. He picked it up and was waving it around like it was a toothpick. So when they were all done, I thought, ‘Let’s see what this is all about.’ I walked over to the corner and grabbed ahold of the bat. I could barely pick it up. The fact that he was strong enough to wave it around like a toothpick was somewhat astonishing.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Content

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Henry Aaron hits home run No. 715

MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

Bill Veeck, Eddie Gaedel and the Birth of Legend

1974 Hall of Fame Game

Piazza jersey from first game after 9/11 continues to inspire

Hoop Hall legend Dan Issel visits Cooperstown

Frank Robinson Traded to Orioles

Wendell Smith Chronology

Open and shut down

Hall of Fame Weekend 2017 to Feature Inductions of Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez, John Schuerholz, Bud Selig, July 28-31 in Cooperstown

01.01.2023

Robin Yount and Dave Winfield were picked No. 3 and No. 4 overall in the MLB Draft

01.01.2023

Hall of Fame Celebrates Baseball’s Love of Bubble Gum by Teaming Up with Big League Chew

01.01.2023