- Home

- Our Stories

- A Number of Changes

A Number of Changes

Since the earliest days of professional baseball, fans have had a fascination with numbers. And few games produce the amount of numbers – and implement ways to record them – like baseball.

As a result, fans and historians have inherited a treasure trove of numbers from the generations before them. Those numbers – and the records they represent – are preserved in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s One for the Books exhibit.

But the story of the numbers themselves is not as simple as putting pencil to paper. And the numbers themselves – once thought to be absolute – are constantly evolving in the light of new research.

Newspapers carried box scores starting in the middle of the 19th Century, and by the 1880s there were annual baseball guides with summaries of the previous year. The first comprehensive encyclopedia of baseball records was “Balldom,” published by George Moreland in 1914. This volume of 300 pages contained historical summaries of the teams, career totals for star players as well as a listing of notable achievements, such as Rube Waddell’s record strikeout total of 349 in 1904. Many other encyclopedias and record books have appeared since then, some of which are now available online.

For the past half century or so, there has been a widespread, nearly fanatical, belief in the accuracy of the published totals. There has also been a huge increase in high quality, detailed baseball research in this time, some of which has demonstrated clearly that many of the widely accepted records are incorrect.

For example Waddell’s 1904 strikeout total was once thought to be 343. As research continues, even more significant records have cast into doubt. Perhaps the most famous case of a revised record involves the 1910 American League batting race in which baseball historian and statistician par excellence, Pete Palmer, discovered a serious error in the official daily records for Ty Cobb. One game had been entered into the totals twice. The ultimate results were that the winner of the 1910 AL batting title was Napoleon Lajoie, not Cobb, and also that Ty Cobb’s career hit total was wrong. The Sporting News, the most important baseball publication of the time, agreed and publically announced these changes in 1981.

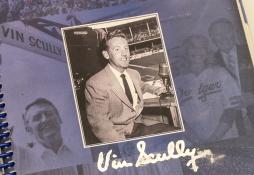

One of the more thoughtful analyses came from the late Leonard Koppett, a long-time sportswriter and author of excellent baseball books who in 1992 was the recipient of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Koppett acknowledged the uncertainty and unreliability of many records, but urged that great caution be exercised in making changes. In doing so, he emphasized the need for an “official” version of important records since he saw the alternative as “dueling statistics” with the result of chaos and disrespect for records in general.

Koppett eloquently pointed out that “official” means “from the office”, not “accurate”. That is, the designation carries with it authority and credibility, but the records may or may not reflect what actually happened.

Although Koppett’s concern is a serious one, historians continue to delve into old records and many more discrepancies have been discovered. It is hard to rank the differences that have been found as to their relative importance since one could argue that it is appropriate to get ALL records to be accurate, no matter the category or the player.

A watershed in the visibility of these issues was the 1969 publication of the first edition of the MacMillan “Baseball Encyclopedia.” This volume represented thousands of hours of work by researchers combing through old record books and newspapers and was a gigantic advancement in the presentation of baseball statistics. It was warmly received by baseball fans, but generated its own storm of controversy as it presented career totals for several prominent players that differed from the previously accepted values.

Perhaps the two that drew the biggest attention were the totals hits for Cap Anson and the number of games won by Christy Mathewson. Anson’s hits were lowered from 3,081 to 2,995 and Mathewson’s wins from 373 to 367 as a result of the detailed reviews conducted by the MacMillan researchers. Major League Baseball got formally involved so that subsequent editions of this encyclopedia had altered numbers, many of which were inspired by the politics of the records.

Other encyclopedias, notably Pete Palmer’s “Total Baseball,” filled the gaps and provided data that were based on empirical evidence. But the numbers continue to change. Anson’s hit total, for instance, has been listed as no fewer than seven different totals in encyclopedias over the years.

The story of Mathewson’s win total has a bit of irony to it. When he retired in 1916, Mathewson was credited with 372 wins. In 1929 Grover Cleveland Alexander won his 373rd game to apparently set the record for wins by a National League pitcher. However, an early historical review in the 1940s discovered that Mathewson actually had one more win, so these two Hall of Fame right-handers are now both officially credited with 373 wins.

Part of the issue is basic rules changes. The MacMillan researchers proposed a change for the first edition of the book – one that was nixed as the book was undergoing final reviews before publication – to alter Babe Ruth’s home run total from 714 to 715. The reasoning was that Ruth had been penalized by a rule that was in place in 1918, but has since been changed: The rule determining the value of game-ending hits. Ruth hit a ball over the fence to end the game of July 8, 1918 and give the Red Sox a win. Under the rules of the day, he was not credited with a home run, but only a triple, since the man who scored the winning run had advanced three bases on the play. In modern times, of course, the hit would be a home run.

In an effort to apply rules in an even-handed way and thereby improve the validity of inter-era comparisons, the decision was made to change all of those hits to homers, effectively applying the modern rule retroactively. There are a lot of “sacred” numbers in baseball history and 714 has been one of them for a long time. That proposal was rejected, and all of those newly credited homers were changed back to their previous values. Of course, none of the others was nearly as dramatic as making a change on Ruth.

How did these problems arise and how have they been discovered? The two most common issues are clerical/mathematical mistakes and decisions by the official scorer that contradict the rules.

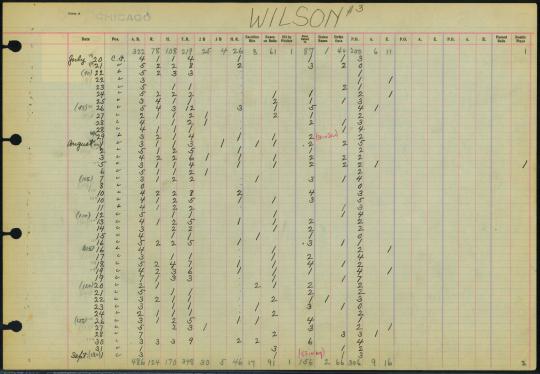

The clerical issues are the easiest to understand and to identify. Prior to the 1970s, all the daily records for each player were recorded by hand in magnificent ledgers – many of which are now preserved in the Hall of Fame Library. The process was for the official scorer to prepare a statistical summary after each game and submit it to the league office, where the totals were transcribed to the individual ledger pages for all the players in the game. At the end of the season, the totals were compiled by hand. I have examined thousands of these ledger pages and have always been extremely impressed with the level of accuracy. Frankly, I know of no other enterprise in which there are so many numbers recorded – millions of data items over the course of Major League history – that has a comparable record of consistency and reliability.

Nonetheless, there are inevitable instances in which numbers were transcribed or added incorrectly. An example of a common issue that has been found is that the total strikeouts charged to the batters on one team must equal the number of strikeouts credited to the pitchers on the other team. Hundreds of cases of these logically impossible mismatches have been identified, and it is not always easy to discern which part is incorrect.

The other category of problems relates to official scorers. These issues are less common, but can be very difficult to unravel. For example, the official daily ledgers for the 1920s reveal that one official scorer in St. Louis did not credit batters with an RBI on a home run, apparently under the mistaken impression that an RBI was only to be credited for driving in someone else, not himself. If the homer in question came with no one on base, then the problem in the ledger is obvious: 1 homer and 0 RBI for a game. However, if there were runners on base when the homer was hit or the batter had RBI from other plays, then properly crediting the RBI requires at a minimum the checking of RBI of all the players for the team in each game.

The statistical record of baseball has always been a key part of the enjoyment of the game and the amount of data available is extraordinary and increasing. Recent decades have seen much greater scrutiny of the underlying information and some problems have indeed been discovered. But the basic reliability of the data has been resoundingly supported while at the same it has become clear that baseball analysis works with a dynamic set of numbers.

The numbers change. The stories, however, remain forever for fans of the National Pastime.

Dave Smith is the founder of Retrosheet