- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Unless you’re a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals, thoughts of baseball in 1967 tend to gravitate toward the “Impossible Dream.” Those improbable Boston Red Sox, even though they did not win the World Series, continue to captivate us as one of the great Cinderella teams of the expansion era. When we recall those Red Sox, we probably don’t think too much about a player like Joe Foy. No, we remember Carl Yastrzemski, and George Scott, and Reggie Smith, and Jim Lonborg, and the manager, Dick Williams. But Foy was a fairly important part of that team, which captured the country's attention during a thrilling four-way pennant race in the American League.

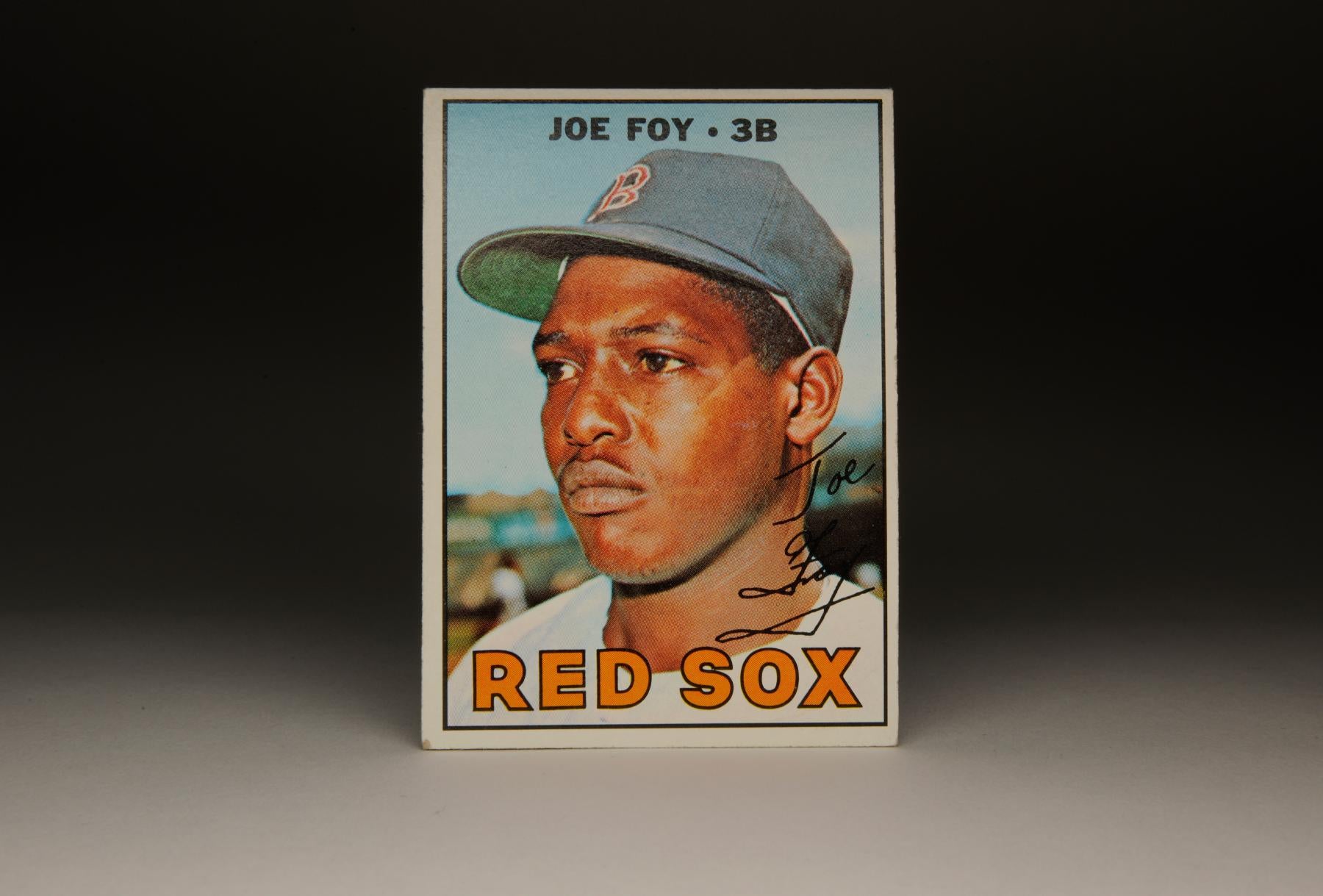

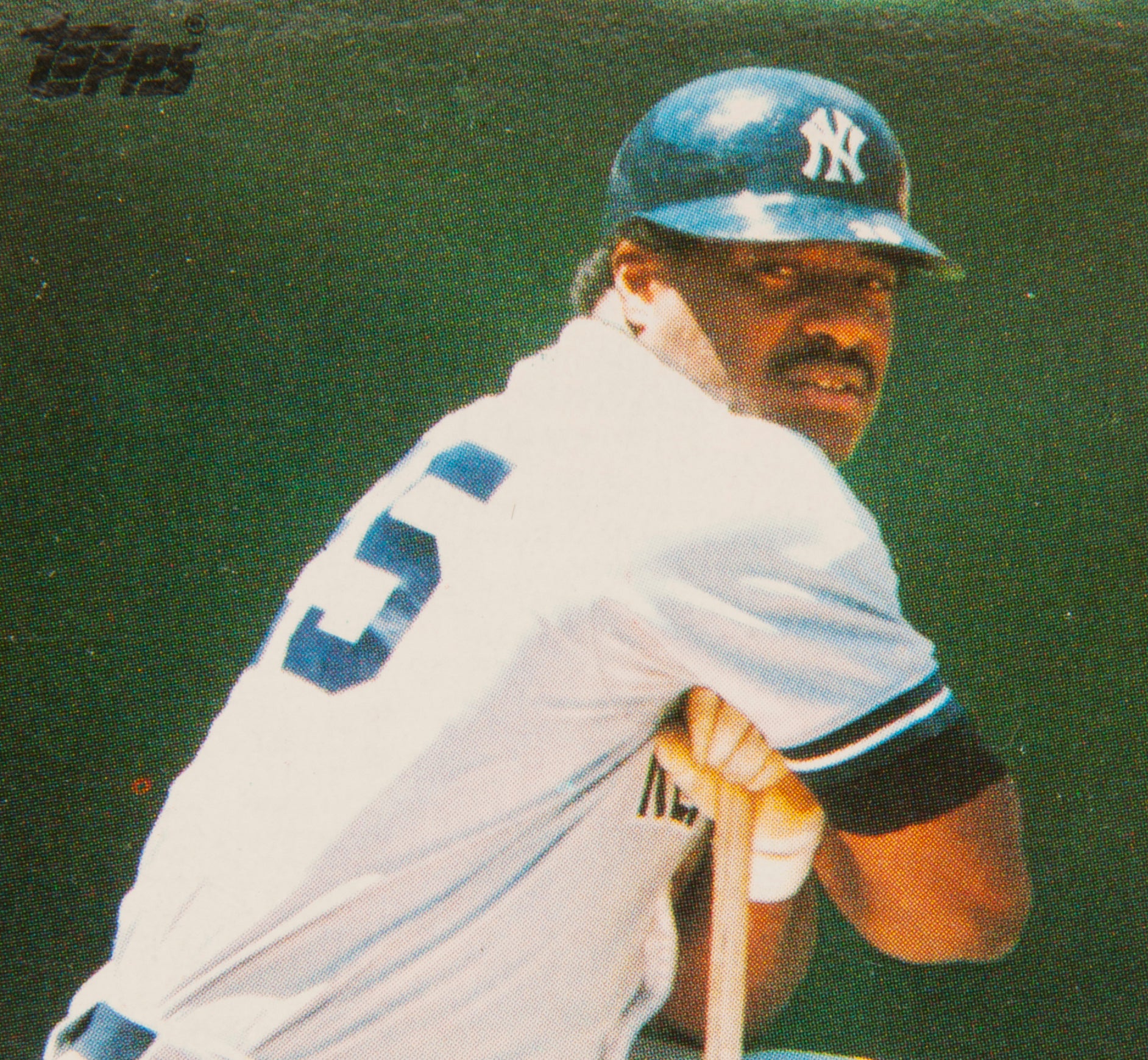

Foy’s 1967 Topps card provides us with an extreme close-up of his face. This was a common way for Topps to photograph ballplayers in the 1960s. Not only do such photographs give us a good look at a player’s facial features, but they also let us examine his expression. In this case, there’s a feeling of uneasiness on his face. That’s understandable. The photograph was almost certainly taken during Spring Training in 1966, when Foy was still a minor leaguer and unsure of his immediate future in the game. He had yet to even make his major league debut. Foy would not completely take over the third base position until later in the season, after the Red Sox decided to rearrange their infield and move George Scott from third base to first base.

Additionally, Foy looks like a fresh-faced rookie on his 1967 Topps card. He appears young and innocent, without wear and tear on his face, just the way that many first and second-year players do. There is no sense of the problems that Foy would face in the later years of his career, when off the field issues cut down the promise of those early seasons in Boston.

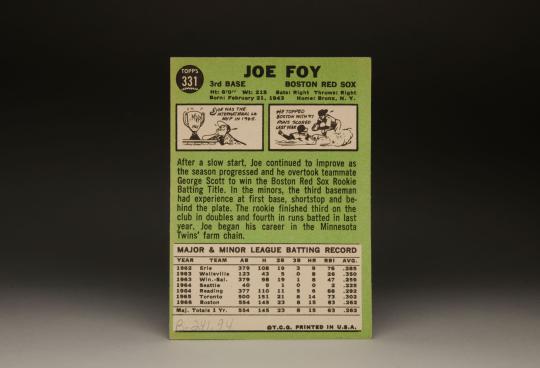

Born and bred in the Bronx, where he emerged as a standout stickball player as a youth, Foy signed originally with the Minnesota Twins in 1962, agreeing to a small bonus as part of his first contract. Foy had what some observers would describe as a roly-poly build, which explains why the Twins tried to make him into a catcher. But they soon realized the switch wouldn’t work and moved him to first base. Playing in the New York-Penn League with Erie in 1962, he showed a discerning eye, drawing an incredible 109 walks in only 113 games. (That’s a rate that would have made Ted Williams proud.) But based on the rules of the day, Foy was eligible for a minor league draft after just one season. The Boston Red Sox pounced, selecting Foy and removing a legitimate prospect from the Twins’ system.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Foy was barely 20 years old and hardly ready for the major leagues, so the Red Sox assigned him to full season Class A ball. The Red Sox also tried to play him as a catcher, but when that failed, moved him back to first base. Eventually, Foy made his way to shortstop, as he continued an unusual career trajectory. In 1964, he moved to third base, where he would settle in. By 1965, he had worked his way up to Triple A. That summer, he hit .302 with 64 walks and 14 home runs for the Maple Leafs. His performance earned him Minor League Player of the Year honors from the Sporting News.

In November, the Red Sox announced that Foy would succeed Frank Malzone as their starting third baseman in 1966. In the spring, Foy played well enough to make the Red Sox’ Opening Day roster, but began the season as a backup infielder. In his place, Scott (a fellow rookie) started the season at third base. That arrangement didn’t last long. Within a week, the Sox moved Scott to first base in place of the slumping Tony Horton and tried veteran Eddie Kasko at the hot corner. When Kasko proved lacking, Foy moved into the starting lineup. Before the month of April was out, Foy was playing every day at the hot corner for the Red Sox.

Foy’s first-year numbers were impressive. Although his .262 batting average looked pedestrian, he drew 91 walks, which raised his on-base percentage into the .360s. He also hit 15 home runs. The only detriment to his game was his fielding, which was erratic at times. Still only 23 years old, and in possession of both above-average power and speed, Foy appeared to have the third base job locked down for years in Beantown.

Foy did not play as well in 1967, but remained a positive contributor on balance, filling a role as an effective No. 2 hitter in the lineup. Early in the season, Foy made a brilliant defensive play to temporarily preserve Bill Rohr’s no-hit effort. The season did bring difficulty to Foy, however. In June, his family’s home in the East Bronx burned down. No one was hurt, but Foy lost most of his possessions and keepsakes.

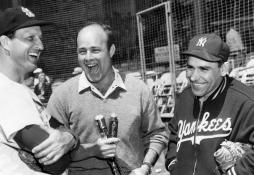

That month brought controversy, too. In a June 21st game at Yankee Stadium, Foy became the center of one of the most memorable brawls in the long rivalry between the Red Sox and the New York Yankees. In the first inning, Tony Conigliaro gave the Red Sox an early lead with a three-run homer. The following inning, Thad Tillotson, a right-hander, threw a fastball up and in against Foy, who had homered the previous game. Somehow Foy managed to duck out of the way of the errant pitch. Apparently not satisfied with his first beanball attempt, Tillotson uncorked another high fastball, this time hitting Foy squarely in the helmet. Though momentarily staggered, Foy bravely remained in the game and took his place at first base, making no effort to incite Tillotson.

When Tillotson took his turn at-bat in the bottom half of the inning, Red Sox starter Jim Lonborg made sure to exact immediate revenge for his teammate, nailing Tillotson with one of his fastballs. As Tillotson made his way toward first base, he hurled a few angry words toward Lonborg. Foy felt it was time to intervene. Walking over from his position at third base, Foy crossed the field and delivered his own message to Tillotson. “If you want to fight, why not fight me?” Foy asked the Yankee pitcher. “I’m the guy you hit to start all this trouble.”

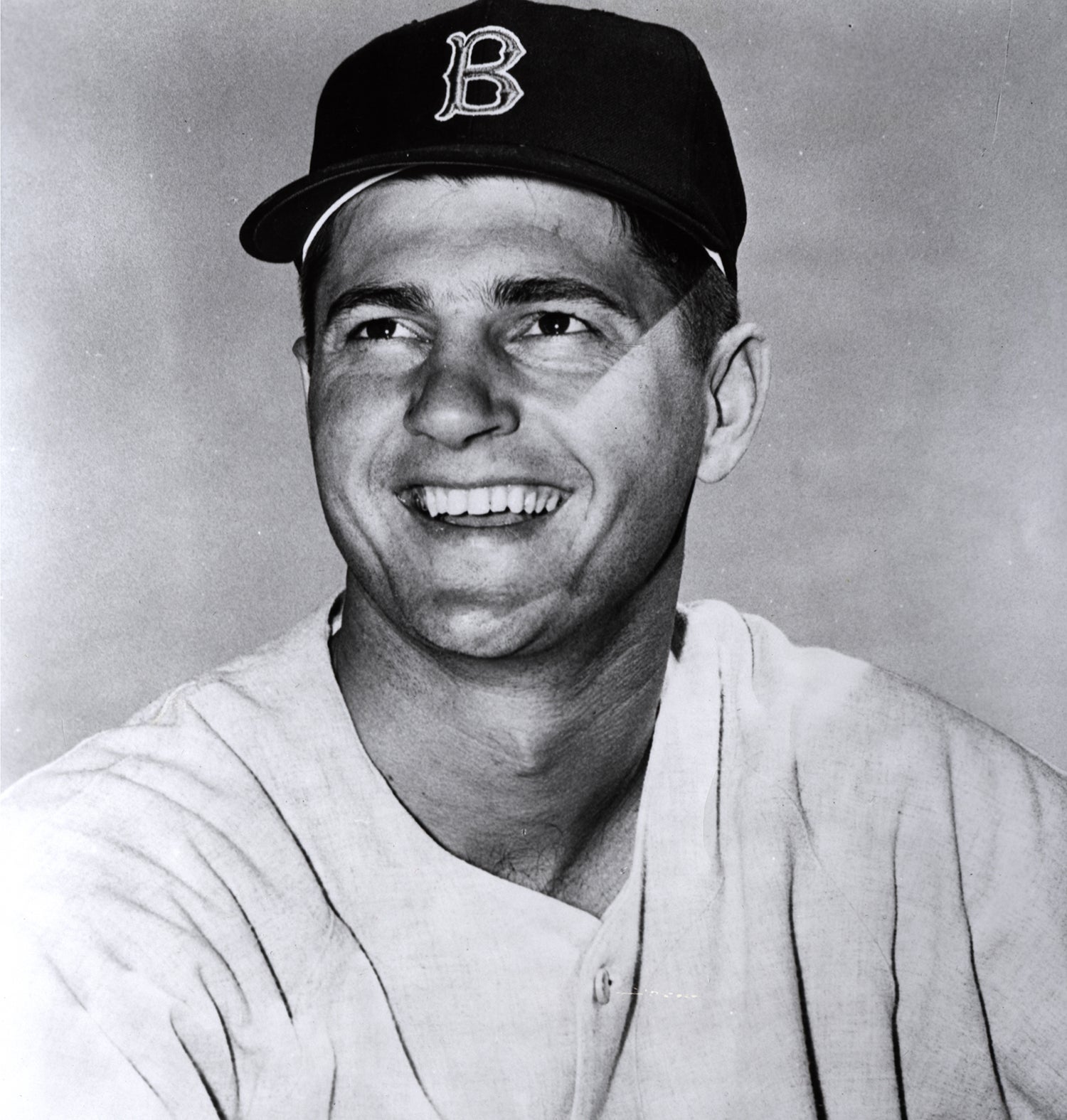

Though it triggered a “pier six” brawl between the teams, Foy’s gesture was the kind that made him popular with his teammates, especially Yastrzemski and second baseman Mike Andrews, who became his closest friends on the team. Generally a positive sort, Foy drew praise throughout the Red Sox clubhouse. When problems with race came up, as they often did in the 1960s, Foy usually tried to provide a solution. Foy knew about racial indignity, mostly through his experiences with Jim Crow segregation in Florida during spring training. As Andrews once said, “If ever there were a black-white problem that needed to be solved, Joe was the bridge.”

As much as his teammates liked him, Foy’s lack of conditioning hurt his standing with management. The team’s new manager, Dick Williams, felt that the six-foot, 225-pound Foy was overweight and out of shape. His level of play proved more erratic in 1967, too. Over the second half of the season, Foy slumped, prompting Williams to begin platooning him with Dalton Jones, a left-handed hitter, and Jerry Adair, who batted right-handed. Foy’s batting average and walk totals fell, but he did hit with more power, connecting on 16 home runs. As a team, the Red Sox surprised all observers, taking over the league lead in August and holding on for dear life, winning a wild American League pennant race in a season that was expected to be little more than a rebuild in Boston.

The 1967 World Series proved frustrating for the Red Sox, who lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games. Foy was benched for the first four games, but when he did play, he delivered only two hits in 15 at-bats, striking out five times against a tough Redbirds pitching staff.

In 1968, Foy reported to the Red Sox at 195 pounds, the lowest weight of his major league career. But both his batting average and power plummeted. Then again, so did everyone’s offense, in a season that became known as the “Year of the Pitcher.” In the context of the era, Foy remained an above-average offensive player, but his fielding became a major concern. Always an iffy defender, Foy committed a whopping 30 errors, the highest total of any American League third baseman.

An off-the-field incident that season also clouted Foy’s future. Foy was driving a car, with teammate Juan Pizarro riding along as a passenger, when the vehicle slammed into a taxi. Boston police arrested both Foy and Pizarro, charging them with being intoxicated in public. The Red Sox were not pleased. They fined both players for breaking curfew, and suspended both for a doubleheader - without pay.

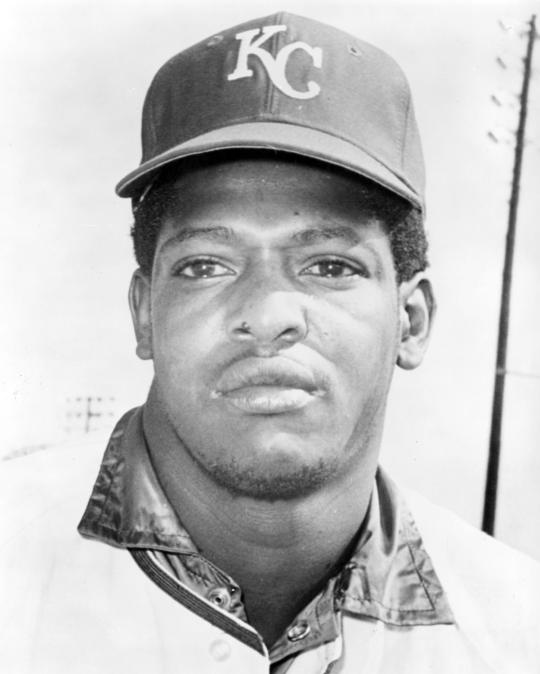

The drunk driving incident convinced the Red Sox that it was time to cut ties with Foy. They chose not to protect him from the upcoming expansion draft. The Kansas City Royals, leaping at the chance to acquire a brand-name third baseman, selected the veteran infielder with the fourth overall pick. The move was difficult for Foy, who felt betrayed by Williams. To make matters worse, Foy’s close friend, Yastrzemski, was now an ex-teammate.

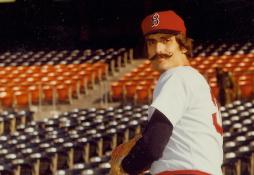

A fresh start in Kansas City helped Foy. He cut his errors down from 30 to 12 and also raised his batting average into the .260s. Given more freedom in running the bases, he stole a career high 37 bases. He also showed versatility by playing five positions for the Royals. Foy did such good work that he drew interest on the trade market. The New York Mets, who had been searching for a long-term answer at third base ever since their 1962 inception, pursued Foy hotly. They agreed to surrender two of their top prospects: outfielder Amos Otis, who had struggled in trying to make the transition to third base, and hard-throwing right-hander Bob Johnson. The Royals simply could not turn down such a hefty offer for a player who been selected in the expansion draft only one year earlier.

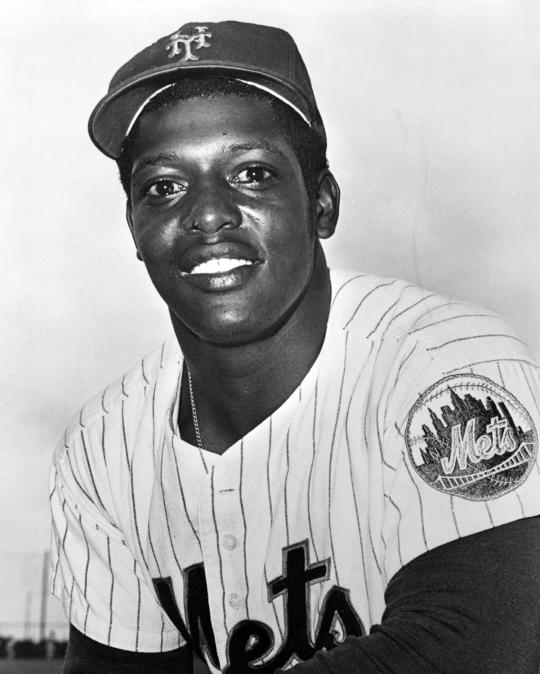

Foy was thrilled to be heading home, playing games in Queens, just a short drive from his birthplace in the Bronx. The Mets believed that Foy, an improved fielder with line-drive power and a patient eye, would settle third base for years to come. It didn’t happen. Foy allegedly became involved with drugs, particularly marijuana. There were also reports of substantial drinking.

During the first game of a doubleheader in 1970, Foy tested the patience of Mets manager Gil Hodges. While in the dugout, Foy walked in front of Hodges during a pitch, stood there, and began cheering. In blocking Hodges’ view during the game, Foy had done something that was simply not done in the Mets’ dugout. Later that day, in the second game of the doubleheader, Hodges started Foy at third base. A batter grounded a ball right near Foy, but he didn’t react, as if he didn’t even see the ball. Even after the ball passed him and rolled into the outfield, he began to punch his hand into his glove, yelling “Hit it to me. Hit it to me.” The other Mets players (and Hodges) looked on in amazement.

Based on his strange behavior in the dugout and on the field, it was suspected that Foy was under the influence of drugs. Mets players wanted Foy removed from the game immediately, but Hodges decided to teach Foy a lesson by keeping him in the game longer.

The incident pretty much sealed Foy’s fate with his teammates and Hodges, the latter having no tolerance for either drug use or a lack of professionalism. On September 12, a few eyebrows were raised when the Mets pulled Foy from their starting lineup at the last minute. That October, the Mets dropped Foy from their roster, demoting him to Triple-A. “We didn’t get a nibble,” a Mets club official told sportswriter Dick Young about the team’s efforts to trade Foy. “His value has become nil.” Later that offseason, the Mets watched the Washington Senators select Foy in the Rule 5 draft.

In 1971, Foy played mediocre ball at the start of the season with the Senators. While with Washington, he commented on the rumors of his drug use. “How many young people in New York do you know who haven’t smoked grass?” Foy told a reporter. That was probably not the answer that the Senators wanted to hear.

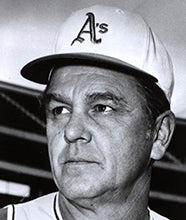

Foy’s manager, the great Ted Williams, soon realized that Foy was out of shape and asked the front office to send him back to Triple-A ball in an effort to lose weight. In 15 minor league games at Denver, Foy batted only .191. One day, Foy argued with Denver’s general manager. Only two hours later, the Senators released Foy. Rather remarkably, at the age of 28, Foy was done playing professional baseball. His major league career, despite his enormous talent, had lasted only six seasons.

Foy’s problems with drugs and alcohol lingered a bit into his post-playing days. He eventually owned and operated a liquor store.

To his credit, Foy overcame his demons. He stopped using drugs. Clean and sober, he lived out his life for the better part of the next two decades. Sadly, his body betrayed him. In October of 1989, he suffered a fatal heart attack at his home in New York City. He was only 46 years old.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

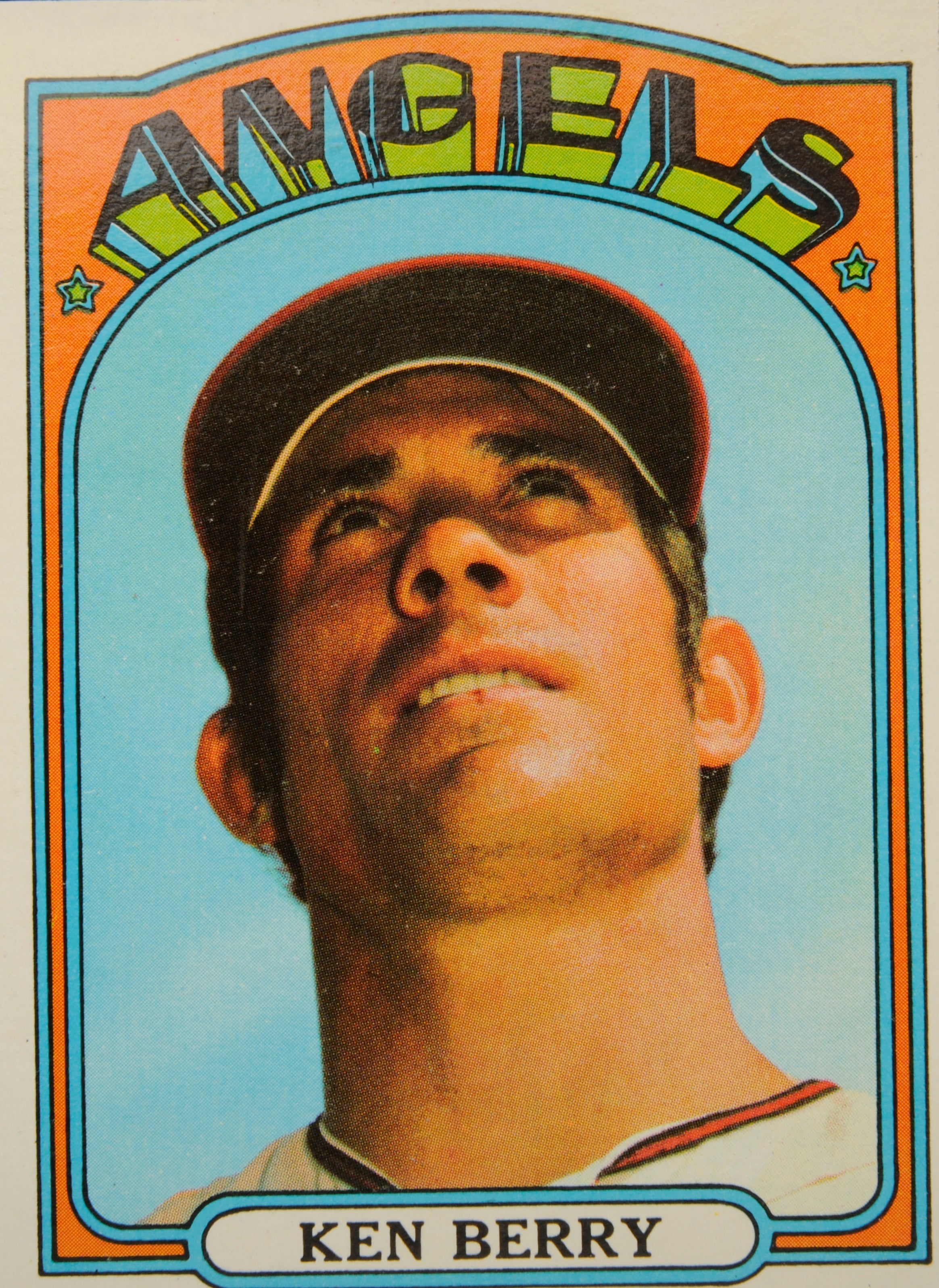

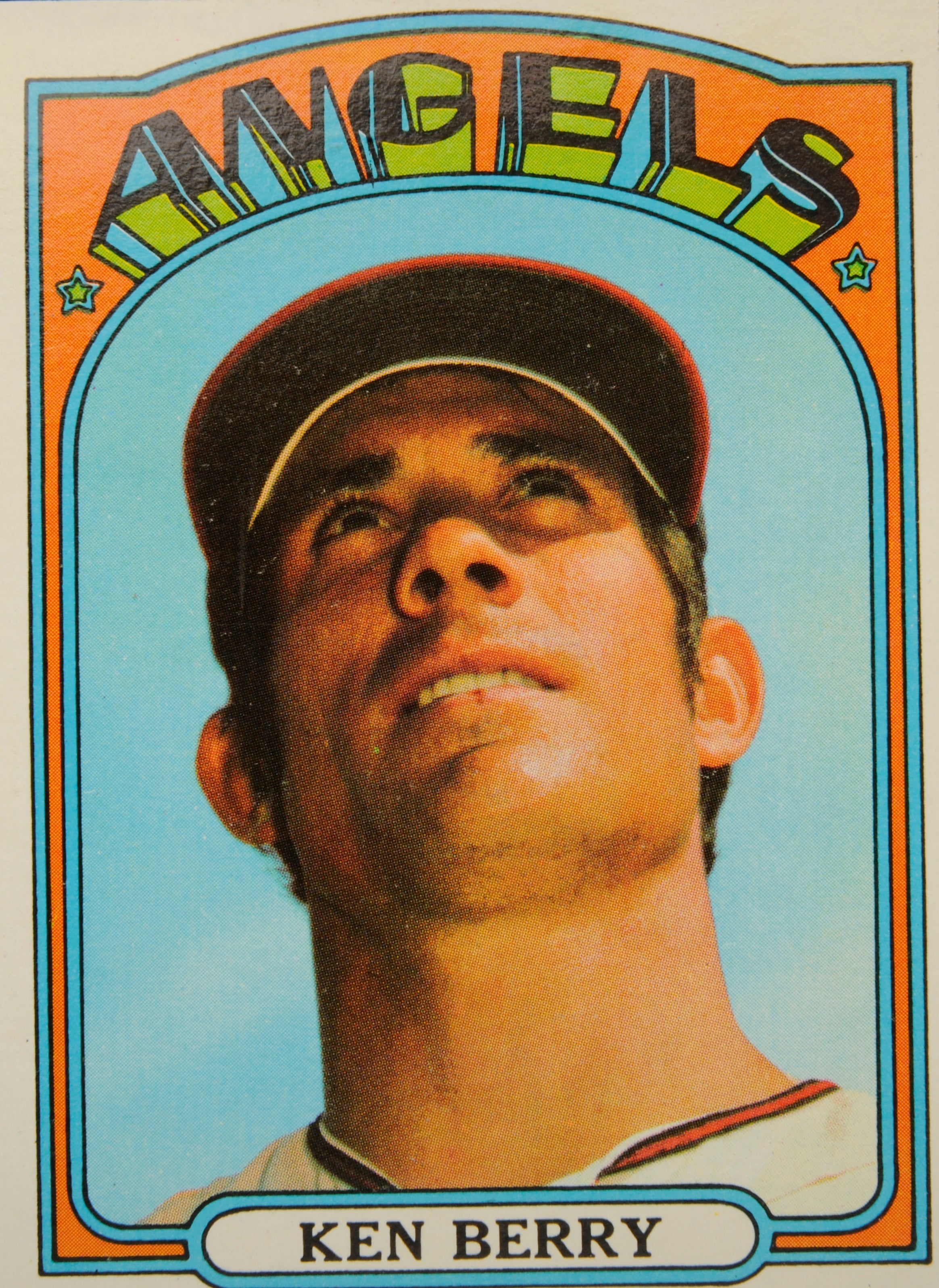

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

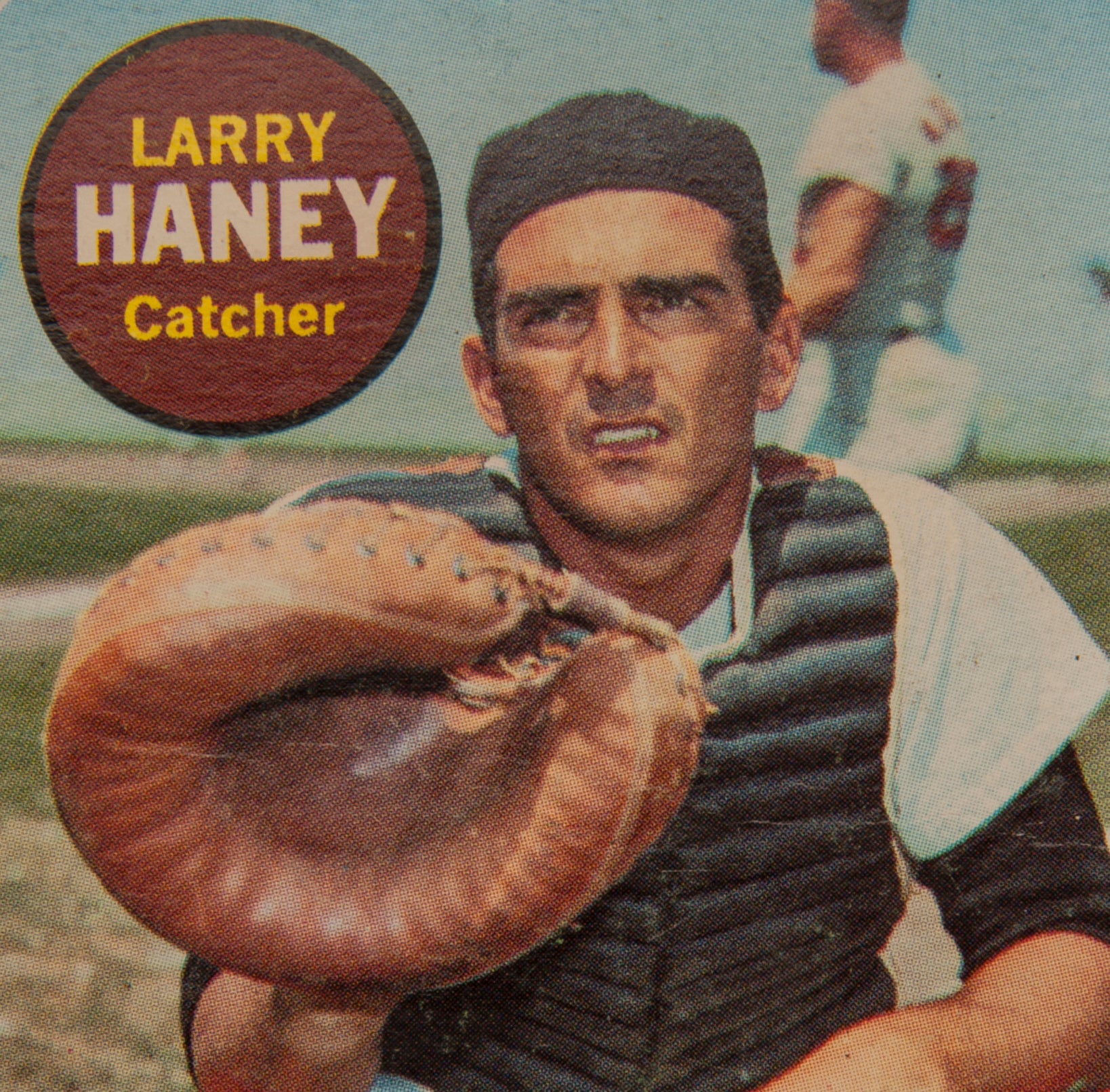

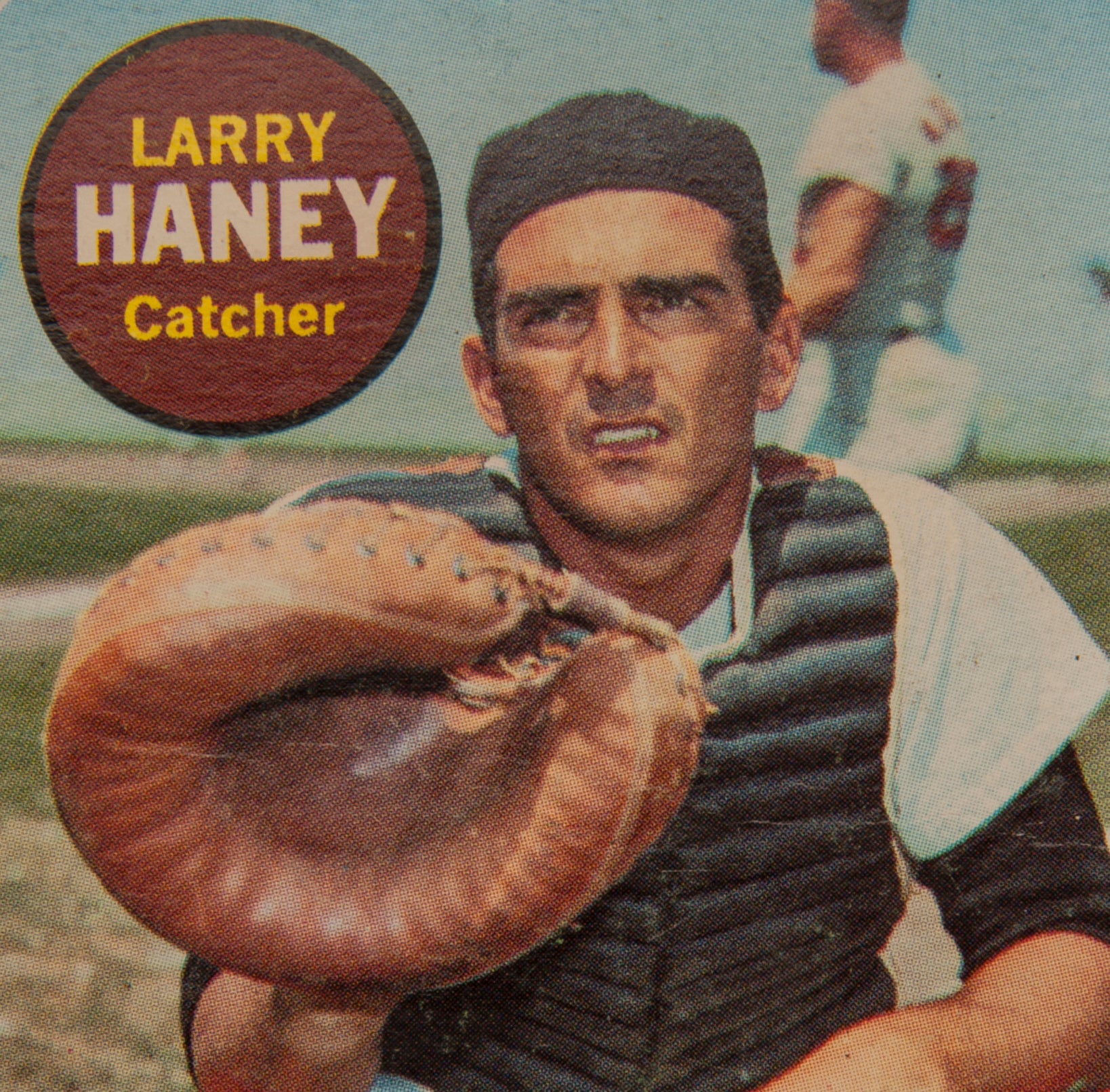

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Satch's Swan Song

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

Blind sportswriter Ed Lucas reflects on remarkable career

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

History Book

#Shortstops: Heroes, Hall of Famers and Sept. 11

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Bob Moose

Tom Seaver Announces His Retirement