- Home

- Our Stories

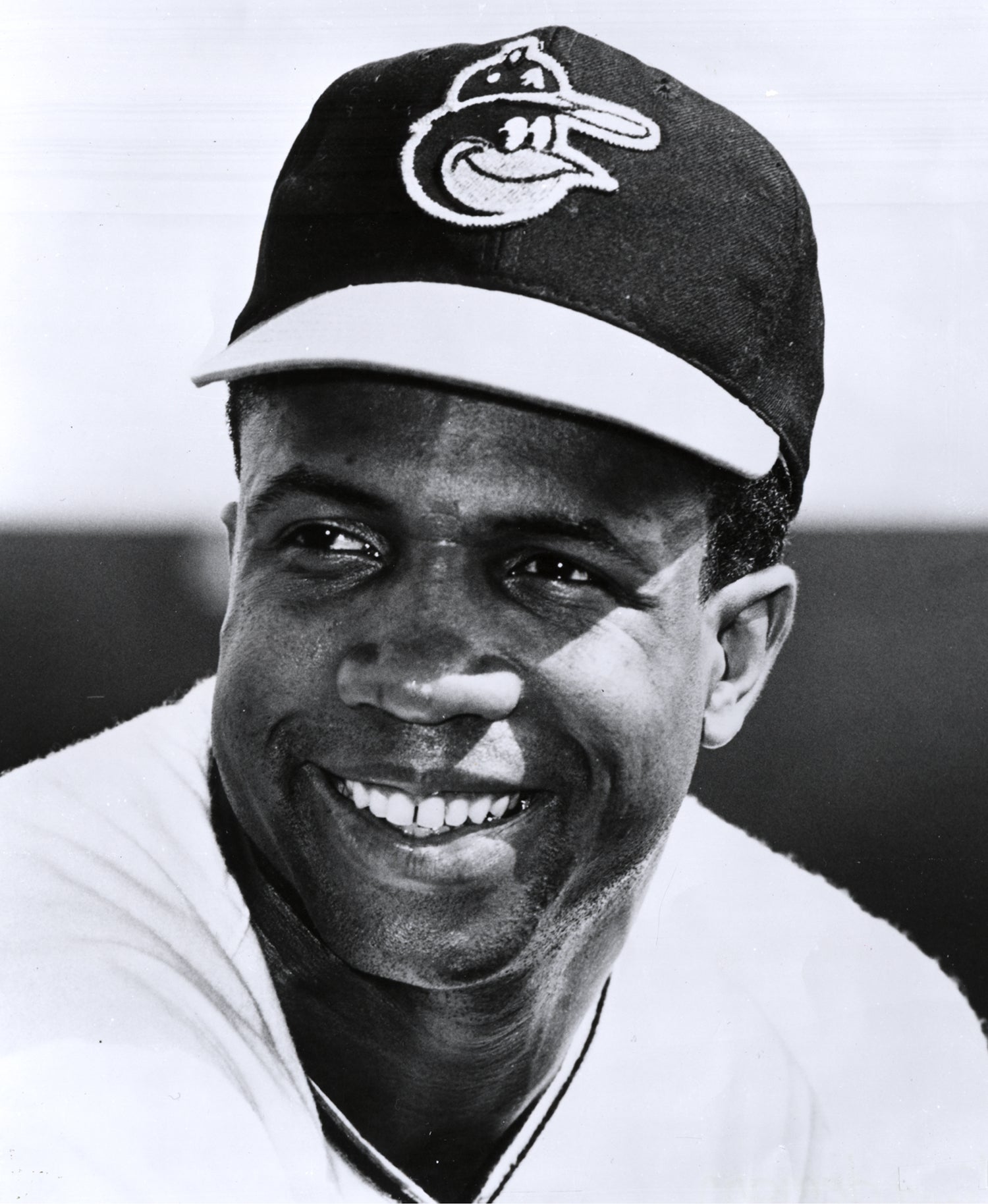

- Frank Robinson made history in AL and NL

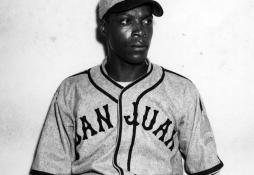

Frank Robinson made history in AL and NL

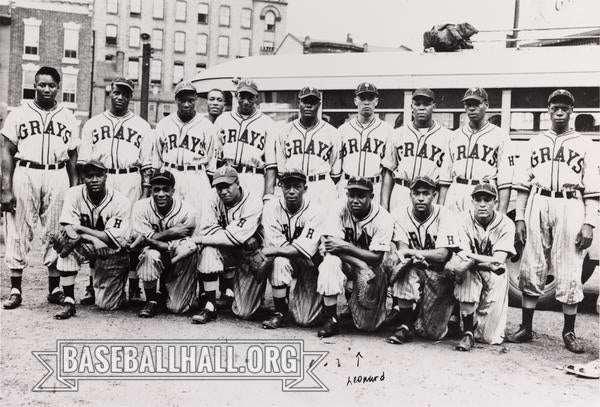

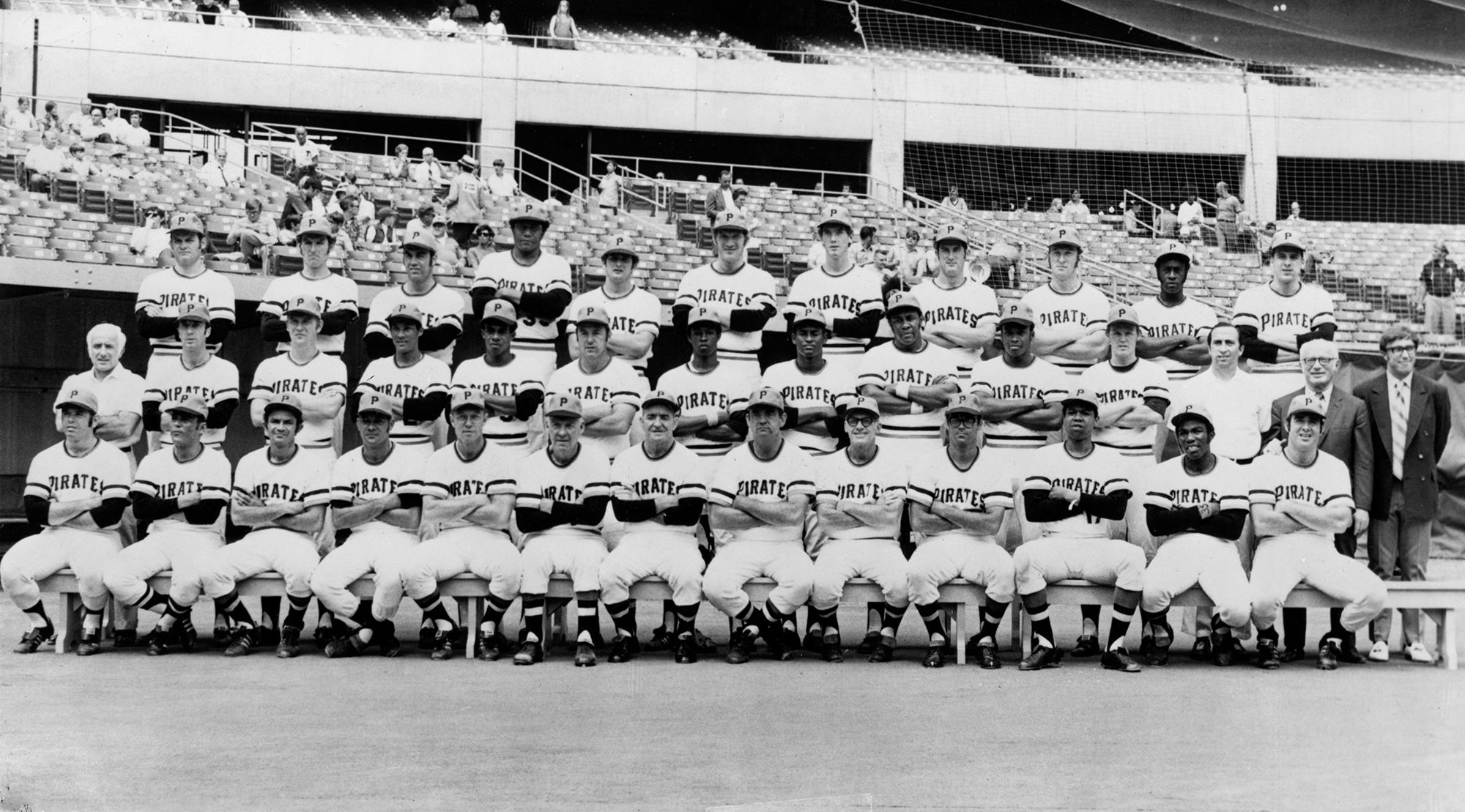

By the summer of 1974, baseball had already achieved several racial milestones: Jackie Robinson emerging as the first modern day Black player in the National League in 1947, Buck O’Neil becoming the first Black coach in 1963, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ fielding the first all-Black lineup of 1971, and the 1974 crowning of a new home run king in Hank Aaron. But other goalposts remained elusive, perhaps most prominently the lack of a Black manager in either the American or National League.

In the years leading up to that summer, rumors had swirled about a few potential candidates. They included Maury Wills, who had retired as a player after the 1972 season, and Satchel Paige, who last pitched in 1965 and was already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There had also been conversation surrounding Roberto Clemente, who was planning to retire after the 1973 season and had long been rumored as a managerial candidate, only to lose his life in a horrific plane crash at the end of 1972.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

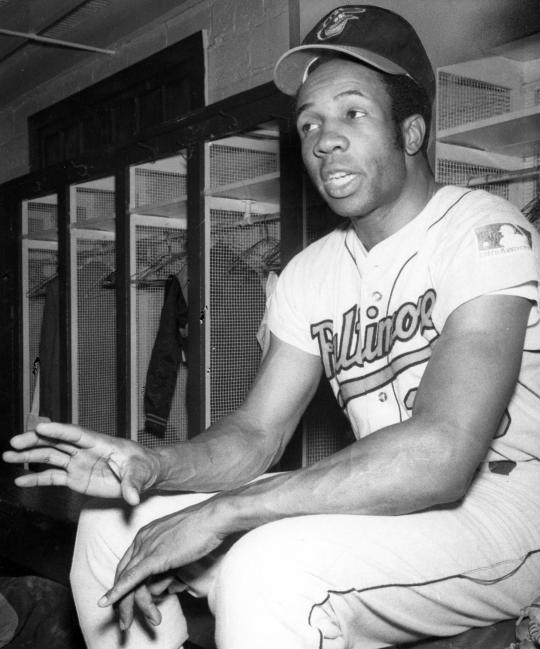

Another candidate loomed as a strong possibility, even though he remained an active player. Frank Robinson, one of the lynchpins of the great Baltimore Orioles teams of the late 1960s and early 70s, seemed like a logical choice, based on his status as the team’s emotional leader. Fiery and hard-charging, Robinson played the game as intensely as anyone, particularly in the way that he took out middle infielders on potential double plays.

Off the field, Robinson garnered respect from all corners of the clubhouse. For example, Robinson ran the Orioles’ “Kangaroo Kourt,” a mock form of justice employed by several major league teams. Meant to keep the Orioles players relaxed and loose, The Kourt assessed players small fines for anything from baserunning mistakes to wearing their uniforms improperly to maintaining a slovenly appearance in their street clothes. Appointed “The Judge” of The Kourt, Robinson wore a large white mop atop his head during “trials” and ruled with a combination of humor and toughness (with an emphasis on the humor). The comedic setting of The Kourt gave Orioles players an enjoyable way to blow off steam during the long grind of the season.

Even more importantly, Robinson had accrued real experience as a manager. By 1974, Robinson had put in several seasons as a manager in the Winter League, where he oversaw teams that featured a mix of veterans and younger prospects. Robinson drew praise for his tough but fair approach, and his ability to teach the game to the younger generation.

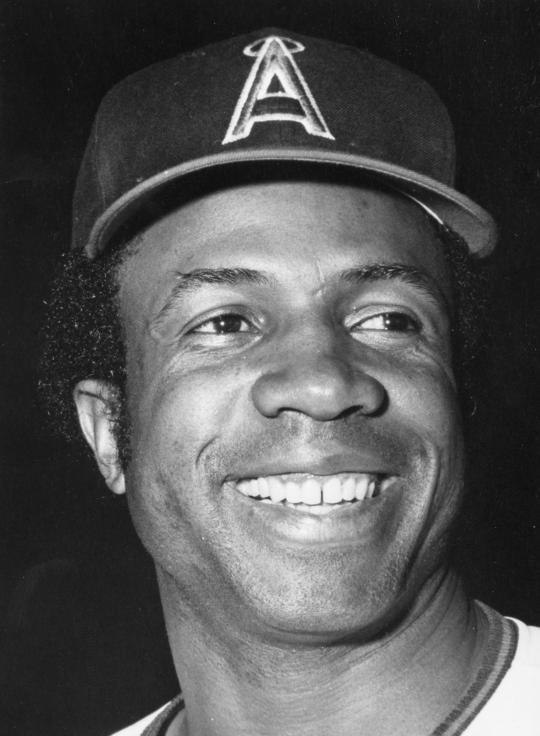

At one point, Robinson seemed destined to make history by becoming the manager of the Oakland A’s. In the aftermath of the A’s winning the 1973 World Series, Dick Williams resigned, leaving the position vacant for the entire winter. One of the persistent wintertime rumors had the A’s making a trade to acquire Robinson, the ex-Oriole who has since been traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers and California Angels. Robinson would become the Athletics’ player/manager, filling two roles as the team’s skipper and primary designated hitter. He still hit with power, even at the age of 37, and would strengthen a position that had been a source of instability for the A’s in 1973.

Assuming that the A’s could adequately compensate the Angels, the addition of Robinson made perfect sense for Oakland. His combination of smarts, work ethic and on-field fire made for a superior managerial resume. And as an added bonus, Robinson had grown up in the Bay Area, becoming a star player at McClymonds High School in Oakland.

On another front, the hiring of Robinson as baseball’s first Black manager would have represented a public relations coup for Charlie Finley. The Oakland owner’s meddling during the World Series drove Williams to depart, upsetting the A’s players and their fan base. At least one of the A’s players – as a matter of fact, their most famous player – seemed to believe that the hiring of Robinson could happen.

“Knowing Charlie Finley, it’s possible that Frank Robinson could be hired,” said Reggie Jackson in an interview with Black Sports Magazine. “Finley wants to be first in everything and the fact that he likes the publicity wouldn’t hurt either.”

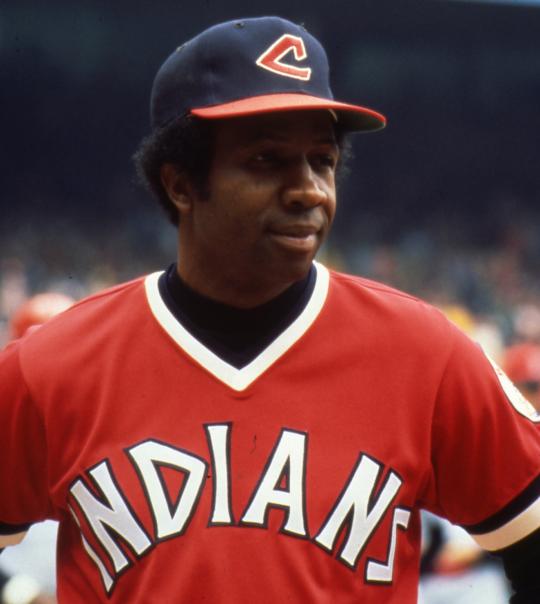

On April 8, 1975, Robinson officially made his debut. On a cold, snowy afternoon, the Indians hosted the Yankees at Municipal Stadium, playing before a crowd of over 56,000 fans. To add to the atmosphere, Major League Baseball invited Rachel Robinson, the widow of Jackie Robinson, to throw out the first pitch. As per Opening Day custom, the Indians’ PA announcer introduced all of the players, along with the managers and coaches. As Robinson wrote in his book, Frank: The First Year, the fans received him royally. “I hurried up out of the dugout and jogged toward home plate. I couldn’t believe the ovation. I’ve had a few big ovations in my career but this was the biggest and best.”

To make the day even more eventful, Robinson inserted himself into the lineup as the Opening Day DH. That prompted his general manager, Phil Seghi, to pull Robinson aside that morning and jokingly suggest that he hit a home run in his first time at-bat. Reacting with mock anger, Robinson responded, “You’ve got to be kidding!”

Remarkably, Seghi’s challenge would turn prophetic. In the first inning, after a pop-out by Oscar Gamble, Robinson stepped in against Yankees right-hander George “Doc” Medich. With the count at 2-and-2, Medich threw a low fastball, which Robinson promptly walloped into the left field stands. As Robinson rounded the bases, the fans at Municipal Stadium treated him to a standing ovation. The Indians went on to win the game, 5-3, capping off a storybook start to the managerial career of the 39-year-old Robinson.

Opening Day represented one of the highlights to Robinson’s first season in the dugout. Another came on May 21, when he blasted two home runs to lead the Indians to a victory over the California Angels. But it was a season that featured a cascade of tumultuous moments, marred by frequent confrontations with umpires. A fiery player, Robinson brought the same intensity to managing, resulting in numerous arguments and three ejections in 1975. Robinson believed that racism played at least a part in his difficult relationship with the American League umpires, all of whom were white. Some umpires bristled at that charge, claiming that Robinson was overly combative and too quick to seek confrontation over controversial calls.

One of Robinson’s low points with the umpires occurred on May 17, when veteran umpire Jerry Neudecker failed to call fan interference on a ball hit to right field. Robinson came onto the field, argued the decision and gave Neudecker a shove. The umpire ejected Robinson from the game. American League President Lee MacPhail later hit Robinson with a three-game suspension.

The Indians’ players came to Robinson’s defense. They circulated a petition, signed by all of the players, which stated they too would sit out all three of the games. Relief pitcher Dave LaRoche showed Robinson the petition. Robinson was flattered by the support but suggested to LaRoche that the players reconsider their decision.

Robinson also had to deal with difficult forces within the front office. Robinson’s boss, Seghi, had a penchant for second-guessing his manager, a trait that rubbed the old-school Robinson the wrong way. Seghi also pushed for Robinson to put himself in the lineup more often, given his track record as a productive power hitter. But Robinson preferred to play only sparingly, appearing in just 49 games, while deferring to Rico Carty as the Indians’ DH. That decision also allowed Robinson to concentrate more of his efforts on the demands of managing.

Robinson also encountered problems with some of his veteran players, including staff ace Gaylord Perry. The relationship had started poorly the previous September, when Robinson first joined the team. Perry went to the media and expressed his desire to be paid $1 more than what Robinson was making. Not surprisingly, that public plea did not sit well with Robinson, with the hard feelings carrying over to the 1975 season.

Another player, Blue Moon Odom, threatened to jump the team, but not over any objection with Robinson. Odom was upset about his contract and wanted a raise of $8,000. Robinson repeatedly talked to Odom about his situation, convincing him to stay with the team.

In spite of the series of obstacles, Robinson guided the Indians to a very decent record of 79-80, an improvement of three and a half games over Cleveland’s 1974 performance. For a team that received little power from three positions – catcher, second base and shortstop – had aging players at first base and DH and received only 15 starts from Perry before he was traded to the Texas Rangers, that win/loss record was more than respectable.

As with most first-year managers, Robinson endured his share of growing pains. But it was also obvious that his intelligence, his intensity, and the experience gained from 21 years as a player made him an above-average manager. And he would only get better over time.

After often losing his temper that first summer, Robinson learned to select his fights more judiciously. In 1976, he returned to the Indians as their player/manager, this time leading the club to an-above .500 record of 81-78. He did earn four more ejections, but his relations with umpires did improve over his first summer.

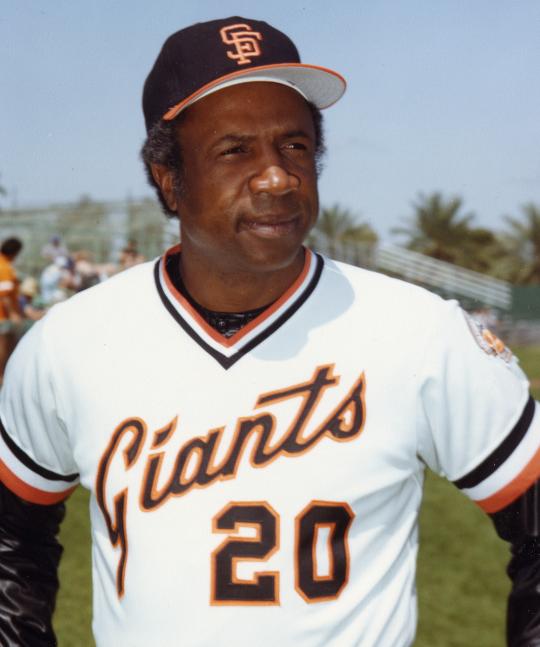

Robinson returned to the Indians for a third season in 1977, but a subpar start of 26-31 resulted in his firing. He would receive a second shot at managing prior to 1981, when the San Francisco Giants hired him as a replacement for Dave Bristol – and in so doing made Robinson the first Black manager in National League history. In 1982, Robinson led the Giants to a respectable third-place finish in 1982. Later on, he would lead a rebuilding effort with his former team, the Orioles. He won a “Manager of the Year” Award in Baltimore, and that, coupled with his work in helping the Montreal Expos and Washington Nationals become perennial overachievers, cemented his reputation as one of the game’s more accomplished managers.

As with his playing legacy, Robinson the manager may remain underrated, especially given the pressure he had to overcome in becoming the first Black skipper in the history of the American and National leagues. Bolstered by his old-school approach and work ethic, along with his deep-seated knowledge of the game, Robinson’s managerial work only enhanced his reputation as one of the game’s wisest and toughest men.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum