- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The Legend of Jim Thorpe

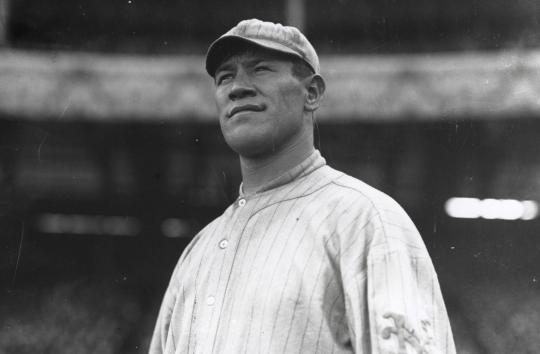

#GoingDeep: The Legend of Jim Thorpe

Arguably the greatest athlete of all time was bedeviled by the curveball, a not uncommon lament for those trying to succeed at the national pastime.

But Jim Thorpe was different. While he played the sport at the big league level with uneven results for a half-dozen seasons, his overall athletic prowess a century ago before embarking on a professional baseball career was already legendary.

David Maraniss, who has written acclaimed biographies on Roberto Clemente, Barack Obama, Vince Lombardi and Bill Clinton, visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in August 2022 for an event surrounding his recently released “Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe” – his 13th book. An associate editor at The Washington Post, Maraniss has won two Pulitzer Prizes for journalism and was a finalist three other times.

“In a sense it's kind of like the third book in the trilogy, starting with Lombardi, Clemente and now Thorpe," Maraniss said. "And in each case, what I look for is both just a hell of a story, the drama of sports, told through this person's life, but also a way to illuminate American history and sociology through that life story. So with Lombardi it was not just about a great coach, but about leadership and competition, success in American life, what it takes and what it costs.”

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

“With Clemente, it’s not just this beautiful ballplayer, but also so many athletes are called heroes and he really was," Maraniss said. "So it was a chance to write about his life and what it meant, in a larger sense, in terms of Latinos in baseball and in the mainland. And with Thorpe, it’s not just this incredible all-around athlete who was unparalleled in what he did. Nobody else before or since has been a gold medal decathlete and pentathlete, all-American football player, a great professional football player, first president of what became the NFL and a Major League Baseball player. But it was also my chance to write about the Native American experience through his life.”

Thorpe won gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, was an All-American football player at the Carlisle (Pa.) Indian School and played in the major leagues for John McGraw’s New York Giants. In spite of this prowess on the field, the member of the Sac and Fox Nation struggled mightily to overcome prejudice and bigotry throughout his life.

Maraniss’ preface to “Path Lit by Lightning” ends with a brief synopsis of his subject’s trials and tribulations, successes and failures:

“Thorpe’s unparalleled athletic accomplishments did not make his life triumphant. His days were marked by loss. The loss of tribal lands. The loss of his twin brother in childhood. The loss of his namesake son at age three. The loss of his Olympic medals and records. His loss of money and security and equilibrium. There is a temptation, then, to view his story as tragedy, but I emerged from my study of his life with a different interpretation. It is also a story of perseverance against the odds. For all his troubles, whether caused by outside forces or of his own doing, Jim Thorpe did not succumb. He did not vanish into whiteness. The man survived, complications and all, and so did the myth.”

In 1950, Thorpe, in an Associated Press poll of 391 sportswriters and broadcasters, was voted the greatest football star of the first half of the 20th century, easily outdistancing such gridiron legends as Red Grange, Bronko Nagurski, Ernie Nevers and Sammy Baugh.

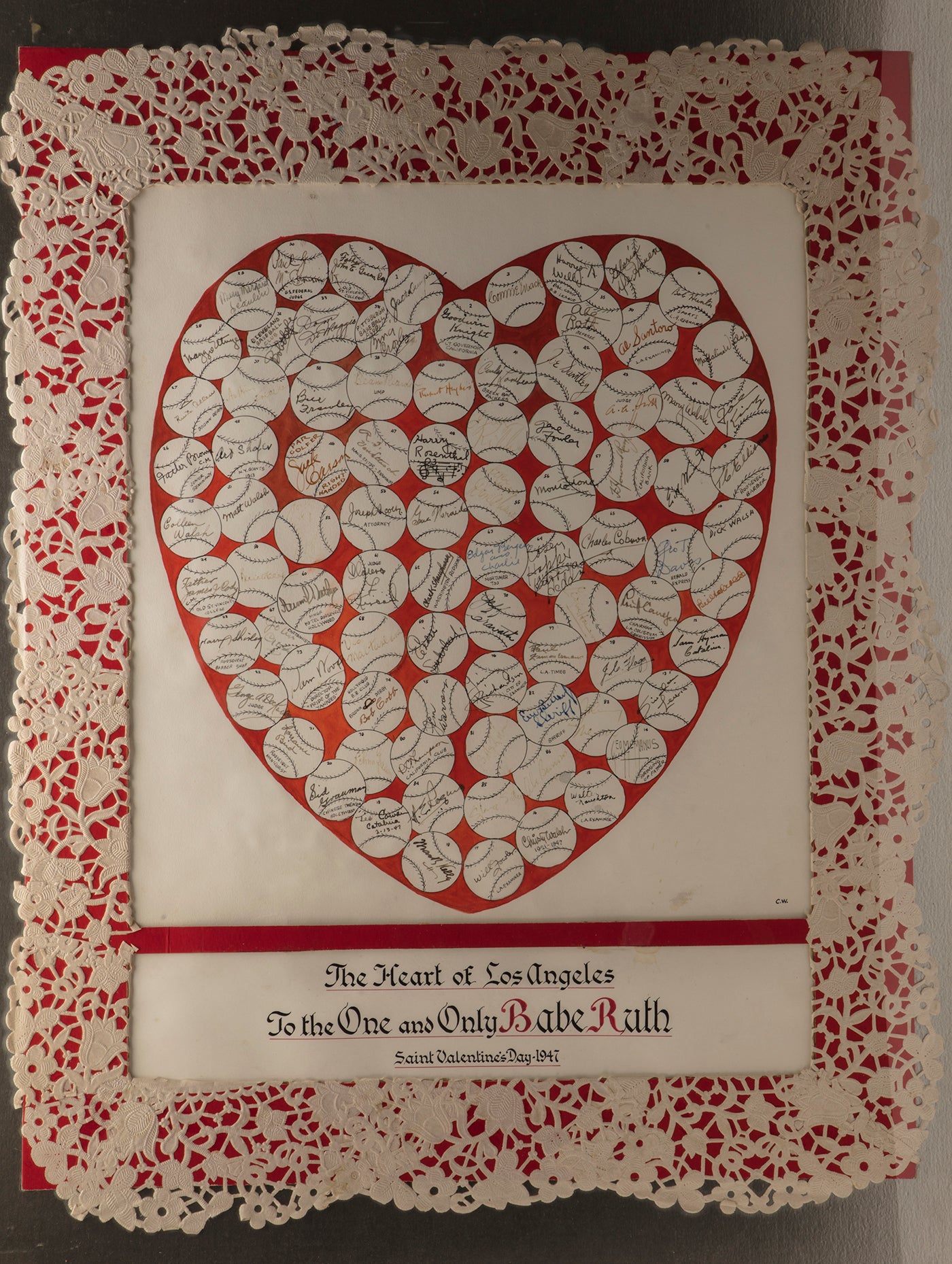

That same year, in an AP poll of the greatest male athlete of the half-century, Thorpe collected 252 of the 393 first-place votes from sportswriters and broadcasters. Babe Ruth, the runner-up, came in second with 86 first-place votes, boxer Jack Dempsey placed third, Ty Cobb fourth, golfer Bobby Jones was fifth and boxer Joe Louis sixth.

“What he did in Stockholm was stunning. Not only did he compete in the 15 events – five in the pentathlon and 10 in the decathlon – he also competed in the long jump and high jump. Think about competing in 17 different events over two weeks. For the decathlon he competed in those 10 events in three days,” Maraniss said.

Reportedly, Sweden’s King Gustav said to Thorpe, “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Soon afterwards, though, Thorpe was forced to return his gold medals when the Amateur Athletic Union discovered that he had played minor league baseball.

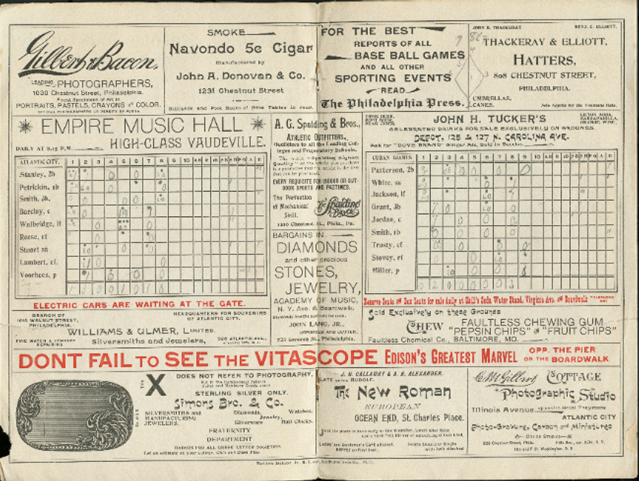

“He played two seasons in the Eastern Carolina League for the Rocky Mount (NC) Railroaders and the Fayetteville (NC) Highlanders in 1909 and 1910,” he said. “But there were scores of college athletes who were playing aliases. It was just common. There was so many aliases in the Eastern Carolina League someone joked they called it the Pocahontas League because everyone was named John Smith. Thorpe played under the name Jim Thorpe. He never tried to hide it. His name was in the papers for two seasons.

“Then after he won the gold medals, the Worcester (Mass.) Telegram ‘broke the story’ by interviewing one of his former managers. The key thing in my book is that Pop Warner, who was his coach at Carlisle, Moses Friedman, who was the superintendent of Carlisle, and James E. Sullivan, who was the head of the Amateur Athletic Union and the American Olympic Committee, all knew and they lied to save their own reputations. Of course, amateurism, in and of itself, was kind of a sham. But he was an easy one to throw under the bus and they did to save themselves.”

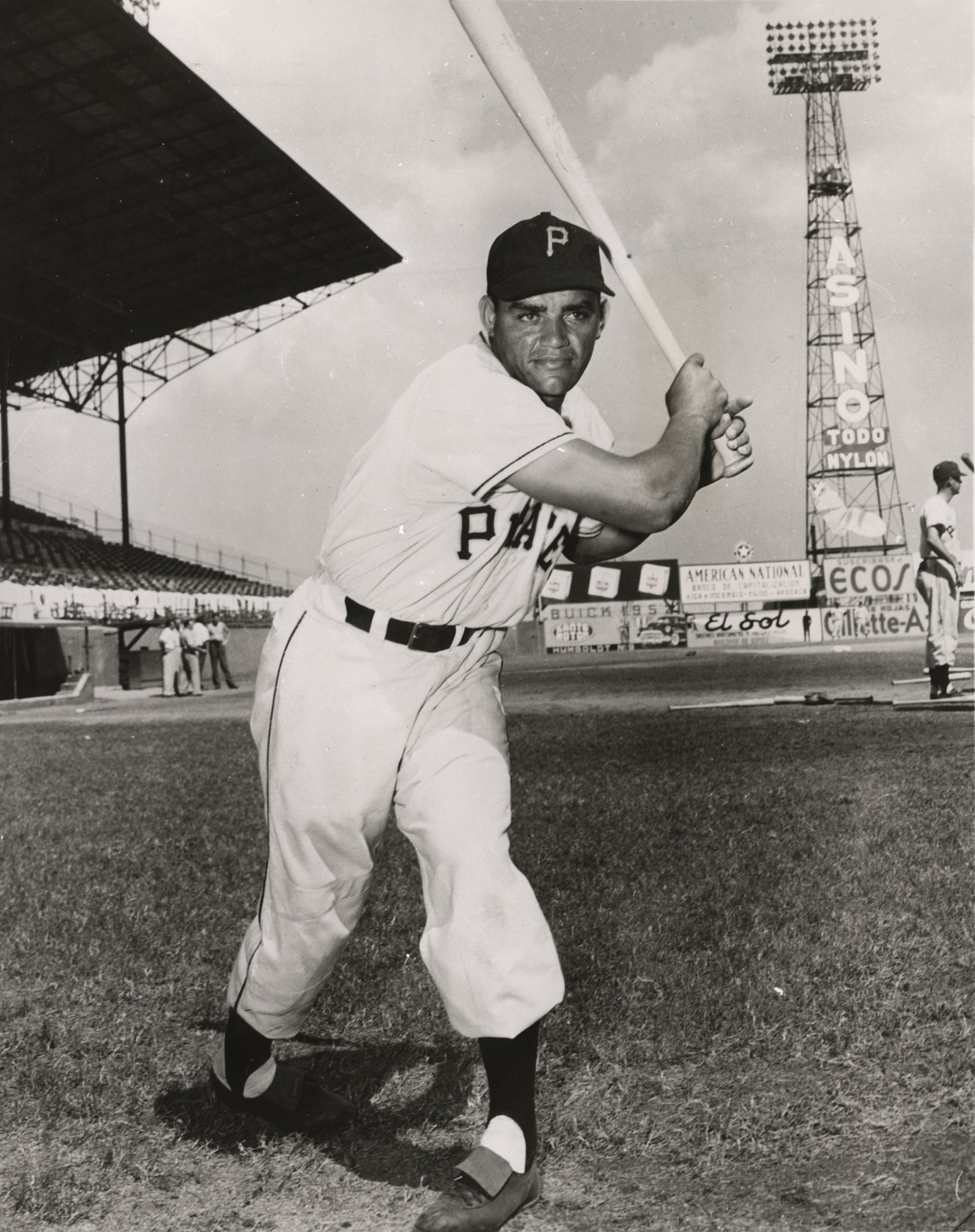

The multi-sport athlete, upon returning to America, turned to a baseball career because athletically that’s where the money was at that time. After signing with the New York Giants, Thorpe embarked on a six-year major league career. Playing mostly outfield, the right-handed batter received sporadic playing time under skipper John McGraw, ultimately playing only 289 games while batting .252 (176-for-698) with seven homers and 29 stolen bases.

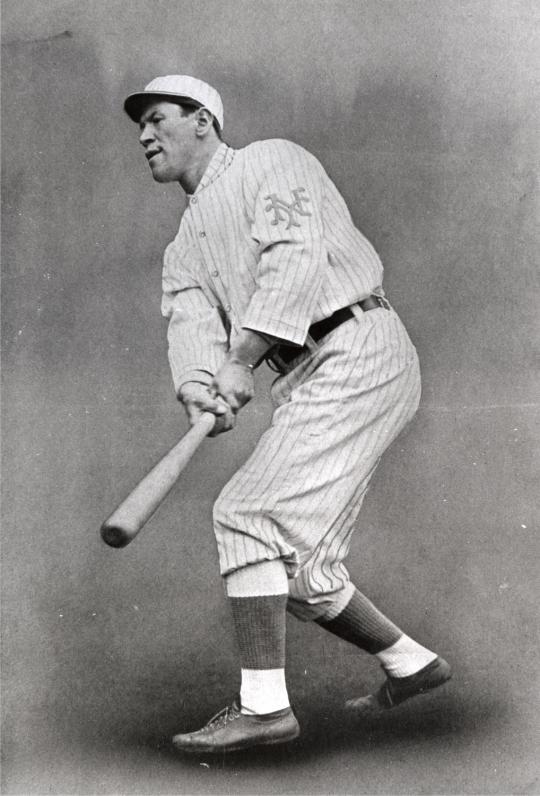

Despite his otherworldly athletic talent, Thorpe had one major obstacle on the diamond: “I can’t seem to hit curves. I believe I could hit .300 otherwise.”

Maraniss’ unofficial scouting report on Thorpe’s baseball prowess?

“It would be that he was fast. He was good at stealing bases. He had some trouble with the curveball. And he had power. But he was mishandled. That's my basic conclusion,” Maraniss said. “He was mostly signed because he was famous.”

John McGraw knew that at the end of that 1913 season, the Giants were going on a world tour with the Chicago White Sox. The teams went to Japan, China, Australia, Philippines, Egypt and Europe.

“There were famous people on that trip from the perspective of the U.S., including McGraw himself and Charles Comiskey, the owner of the White Sox, and future Hall of Famers Tris Speaker and Sam Crawford. But nobody in the world had ever heard of any of them. They knew Jim Thorpe. He was the one that everybody wanted to see on this trip,” Maraniss said. “And similarly, even in the U.S., part of it was to have Jim Thorpe on your team gave it a certain status. But McGraw really didn't give him a chance. He would play in Spring Training and then they'd come up north and he'd sit on the bench. The Giants played in the 1913 World Series against the Philadelphia A’s and Thorpe didn't even get it any games.

“Baseball wasn't his best sport, but he got better the more he got to play. He was never as good in baseball as football, but he was a major leaguer and he proved that he was good enough.”

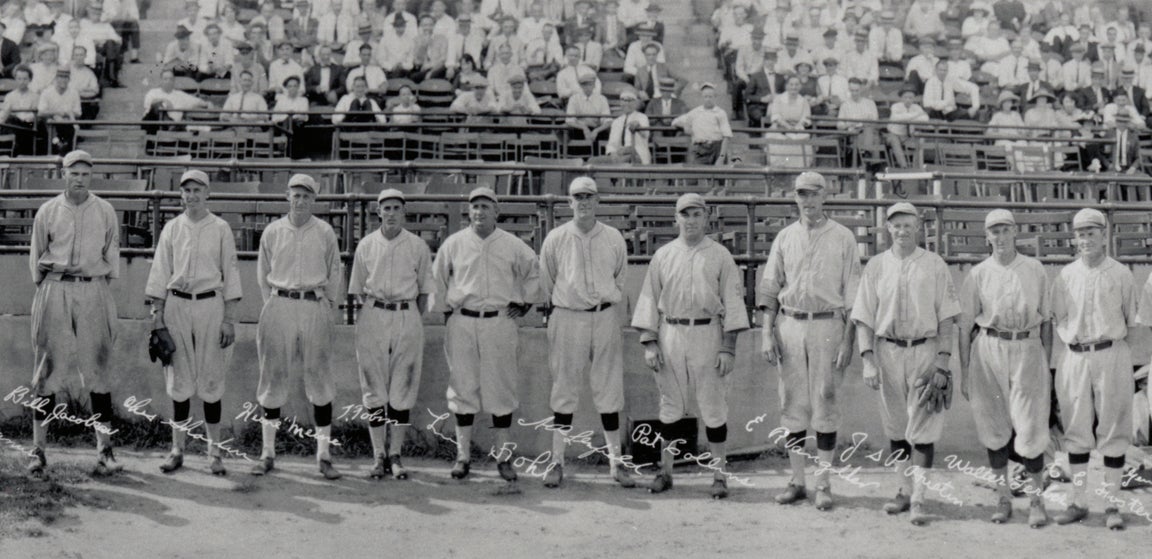

During Thorpe’s time with the Giants his teammates included future Hall of Famers Christy Mathewson, Rube Marquard, George Kelly and Ross Youngs.

“Christy Mathewson took a liking to Jim Thorpe and tried to teach him to play golf, telling him that would help his hand-eye coordination. And Christy Mathewson actually was the manager of the Reds when Thorpe was sent out there,” Maraniss said. “Mathewson and McGraw and many of the famous baseball people of that era had newspaper columns with ghostwriters. Mathewson had one and he wrote a lot about Thorpe during that period.

“Thorpe was kind of a little bit of a wild card in the dugout. He liked to wrestle and McGraw was afraid he'd hurt somebody. But whether he was more of a roustabout than most of the other ballplayers I’m not sure Christy Mathewson, of course, was a teetotaler, but most of them were just like Thorpe.”

The second half of Thorpe’s life was “difficult” according to Maraniss, the once famous athlete living in approximately 20 states seeking some sort of stability.

“He had jobs ranging from digging ditches during the Depression in Los Angeles to being a merchant marine at age 57 during World War II, to being a greeter at various bars at different periods,” Maraniss said. “And the most interesting jobs he had were in Hollywood. We ended up in Los Angeles and he was on the fringes of his studio system. He acted in about 70 different movies and got to know all the Hollywood stars for that period. But he was an extra in most of the movies.

“But what I conclude is you can look at those last 30 years of his life and think it’s a tragedy. This was the best athlete in the world and what happened? A lot of athletes have unfortunate afterlives. That’s just sadly the case. Their best moments of their life come often before age 30. But, more than that, when I was writing those last chapters, I was thinking is this a tragedy or not? And I started to think about why I wrote the book in the first place, which was to illuminate the Native American experience through his life. The number of Native Americans in this country in 1915 was under 300,000, but it's grown ever since as has that self-identity. And so I started to look at that perseverance as a way of looking at Jim Thorpe's life. Yes, he had all of these obstacles, including the ones he made himself, but he just kept trying and growing and persevering.”

Thorpe passed away in 1953 at the age of 65.

In 1983, Juan Antonio Samaranch, then the president of the International Olympic Committee, gave Thorpe’s children replicas of the medals but didn't make him the sole winner of the decathlon and pentathlon. But in July 2022, the IOC made a revision that Thorpe would be reinstated in Olympic records as the standalone winner of the 1912 decathlon and pentathlon.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum