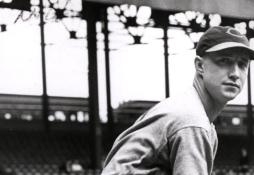

The Fordham Thrush with the .400 larynx.

- Home

- Our Stories

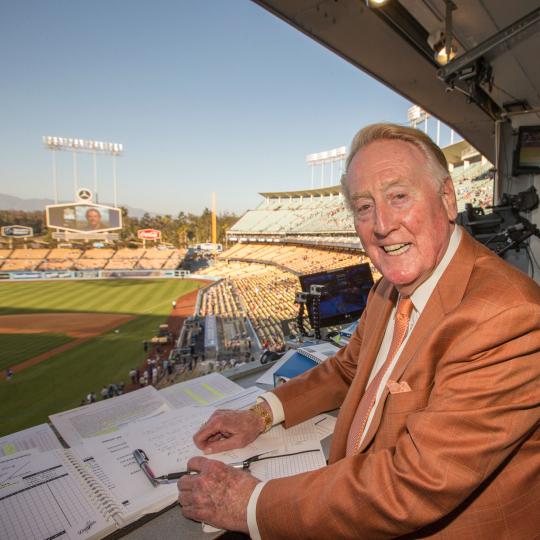

- Vin Scully came to Cooperstown in 1951

Vin Scully came to Cooperstown in 1951

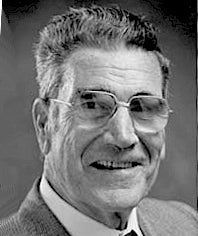

In his 1982 Ford C. Frick Award acceptance speech, Vin Scully related to the crowd that he had climbed to the top of his proverbial mountain and saw the sea.

If Scully had ascended to the summit of his field’s Mount Everest then, he has surely reached the mythical peak of broadcasting’s Mount Olympus 34 years later.

When it’s time for Dodger baseball on Sunday afternoon as they and the Giants meet at AT&T Park in San Francisco, Scully will call the game and then call it quits, ending a 67-season run as play-by-play broadcaster for the Dodgers franchise, first in Brooklyn, then in Los Angeles.

Not too bad for a “red-haired kid with a hole in his pants and his shirt-tail hangin’ out,” who played “stickball in the streets of New York,” as Scully described himself in 1982.

In 67 seasons, consider:

• Scully’s broadcasting career has gone from predating the transistor radio to the days of digital broadcasts and team-owned television networks.

• In the time there has been one Scully broadcasting major league games, there have been three generations of Carays and two generations each of Bucks and Brennamans.

• When he started alongside Red Barber and Connie Desmond in 1950, MLB’s footprint was 16 teams in 10 cities, almost all in the northeastern quadrant of the United States. Now there are 30 teams across North America.

Suffice it to say, Scully has seen a lot of changes over the past 67 seasons. Now Dodgers fans and baseball fans across the world will endure a change everyone knew would come sooner or later, but one which no one looked forward to.

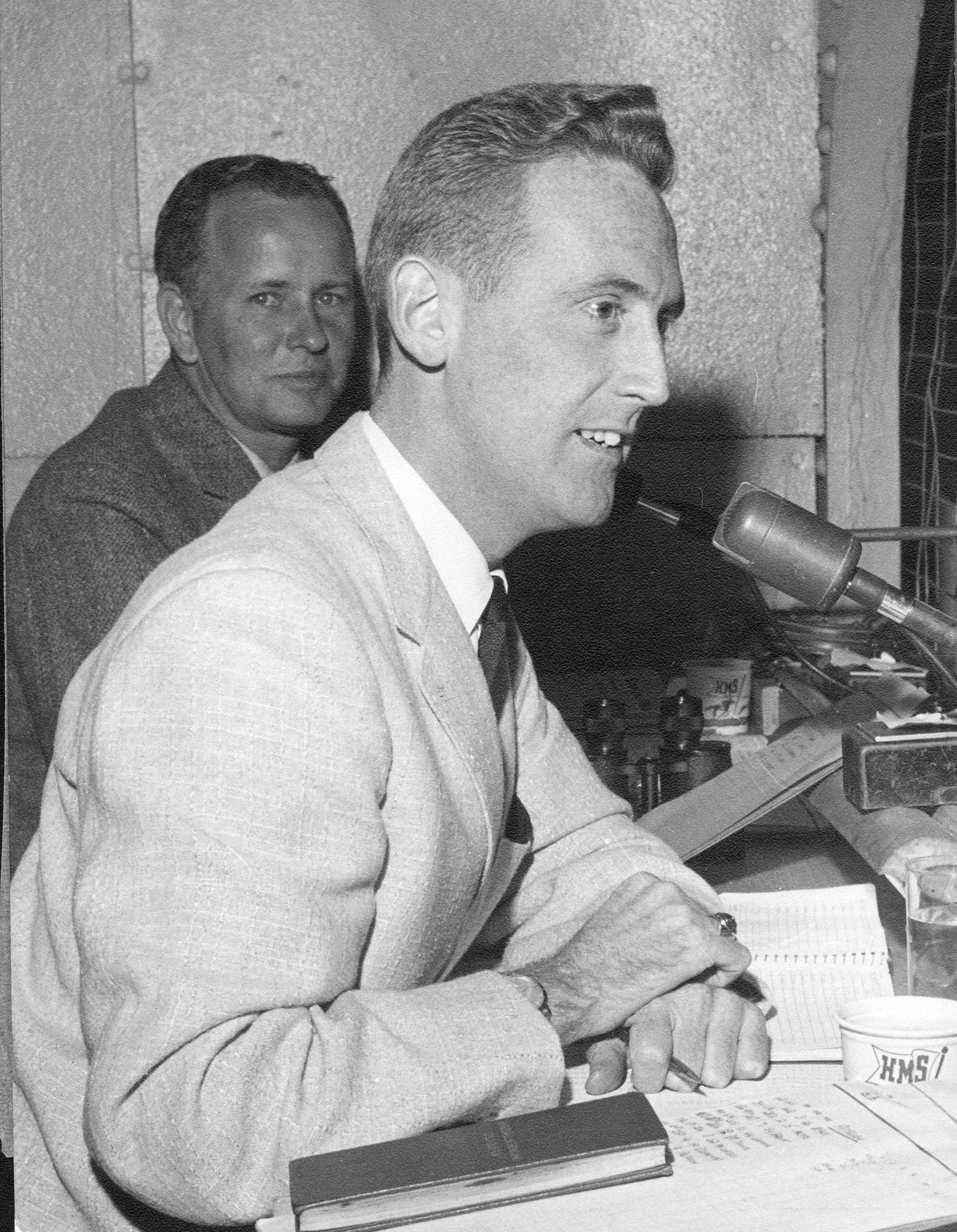

Scully grew up in New York City and graduated from Fordham University, where he had played baseball in addition to broadcasting it, basketball, and football games for the school’s now-famed WFUV radio station. Shortly thereafter, he joined Barber and Desmond on WMGM’s Brooklyn Dodgers broadcasts, beginning his long tenure with the franchise.

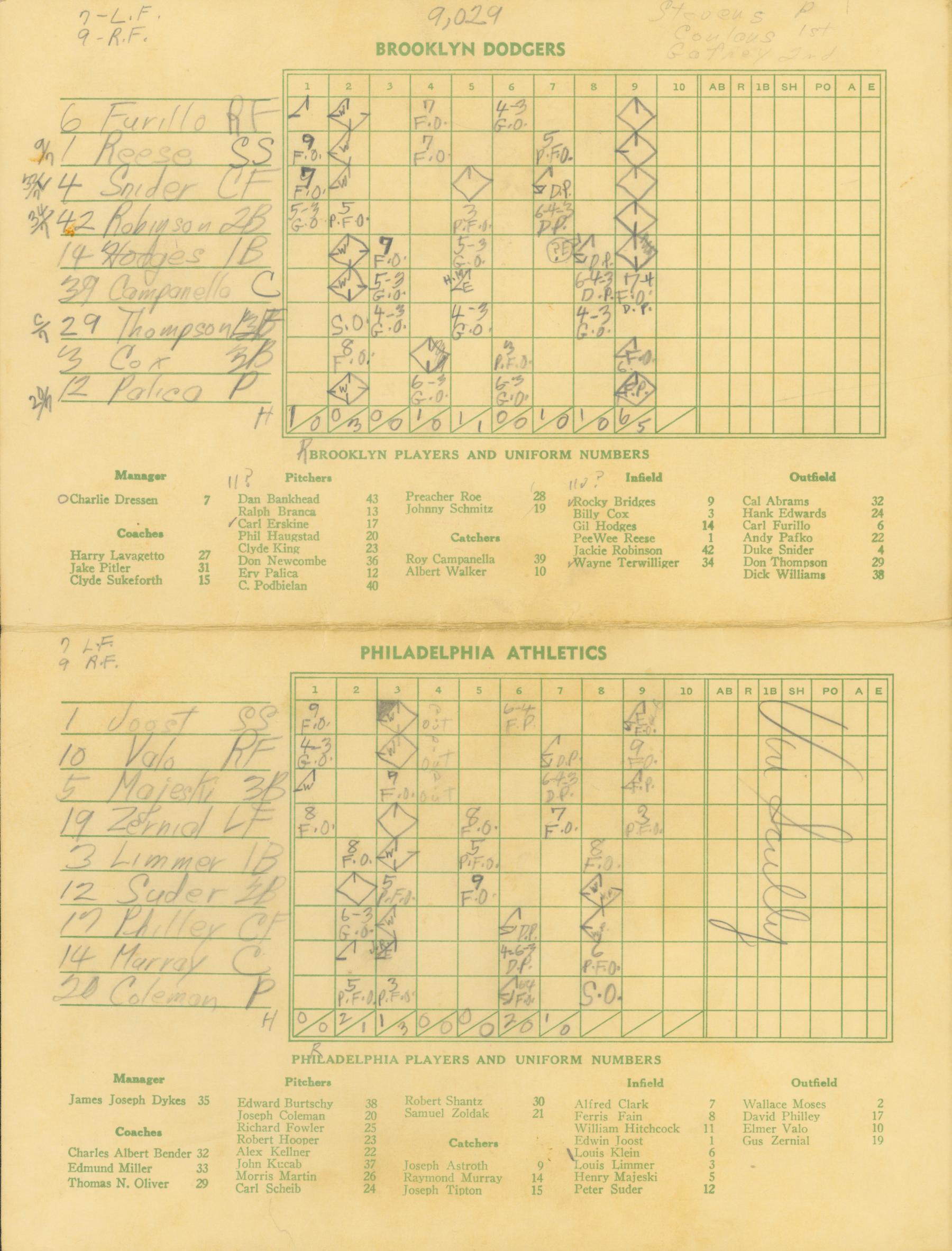

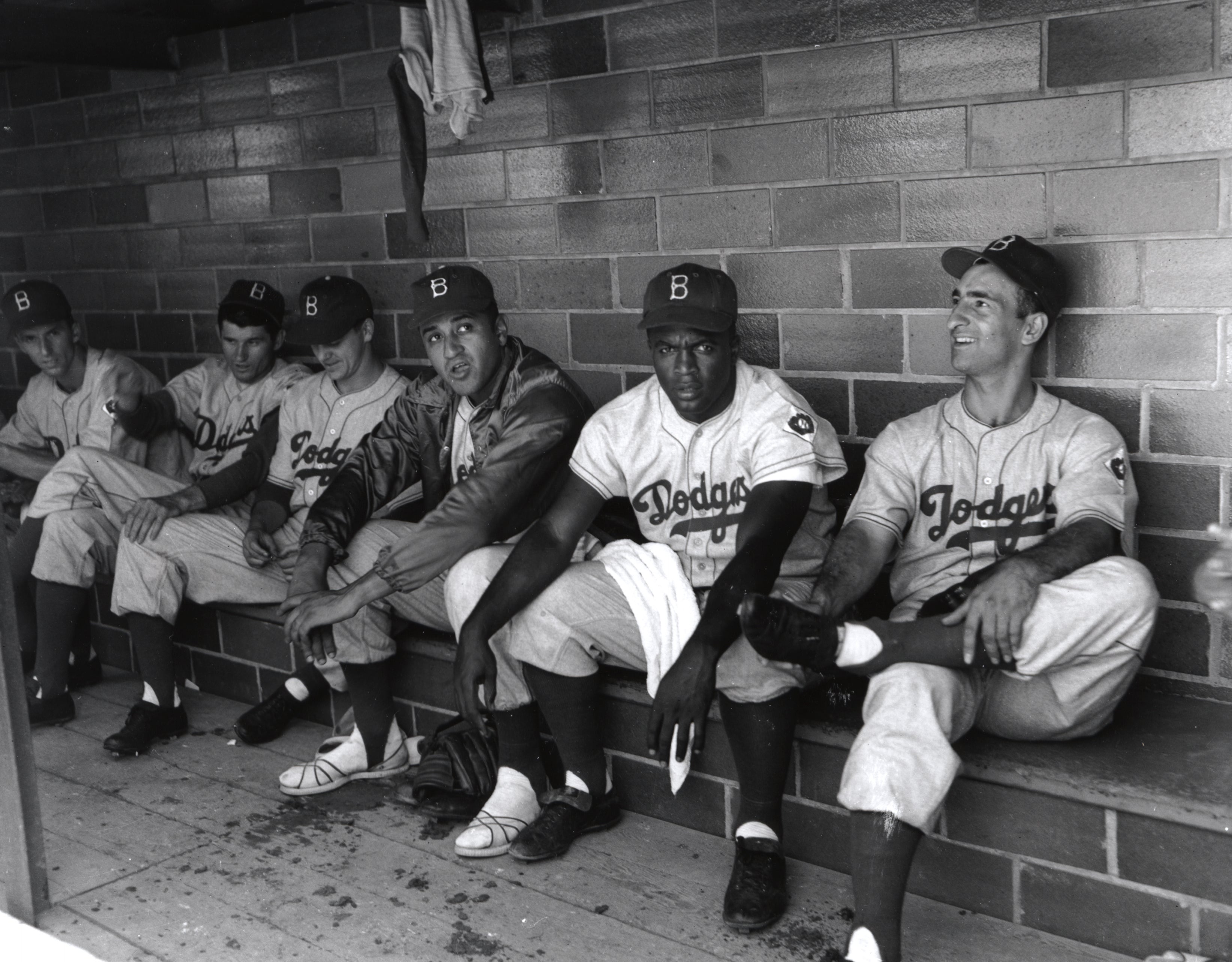

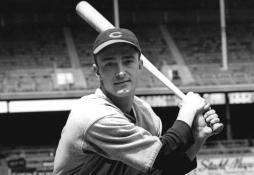

Just a year into his major league broadcasting career, Scully stopped in Cooperstown on July 23, 1951, with the rest of the Dodgers, who were to face the Philadelphia Athletics in the annual Hall of Fame Game at Doubleday Field. WMGM decided to broadcast the game in the New York City area, with Scully behind the microphone. His scorecard from that game, now held within the walls of the Baseball Hall of Fame, details the five-run ninth inning the Dodgers used to vault over the A’s 9-4.

In 1982, Scully returned to Cooperstown to pick up the Frick Award, which described him as “entertaining, precise, proficient, charming, friendly, outgoing, smooth, relaxed, warm, knowledgeable, intelligent, literate, concise, well-prepared, (and) colorful.”

He was, as Los Angeles sportswriter and J.G. Taylor Spink Award winner Jim Murray once said, “The Fordham Thrush with the .400 larynx.”

Interestingly enough, Scully has spent more years broadcasting since he won the Frick Award than he did prior to winning it. But it would not be the only honor he would receive. He has received several honorary degrees and even received the Vin Scully Lifetime Achievement Award in Sports Broadcasting from Fordham.

In addition to his Dodgers broadcasts, Scully has done play-by-play for over two dozen World Series and a dozen All-Star Games. Over the years he has also broadcast college basketball, professional football and golf. He has called no-hitters, perfect games, and various other triumphs and milestone performances.

Yet despite all the honors and all the praise, Scully remains humble and understated about his accomplishments.

“I’m not a military general, a business guru, not a philosopher or author,” Scully told Fordham’s class of 2000 at its commencement exercises. “It’s only me.”

Upon receiving the Frick Award, he wished to “pray with humility and with great thanksgiving” because he had “a lot of thanks to give.”

Even during the festivities honoring Scully, held prior to the Dodgers game on Sept. 23, he responded to the crowd by opening his speech with “Aw, c’mon. It’s only me.”

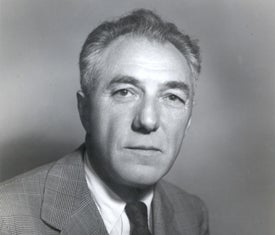

Perhaps this humility comes from working with Barber, a broadcasting great in his own right and fellow Frick Award recipient. Scully’s predecessor as “Voice of the Dodgers,” Barber’s habits quickly rubbed off on his protégé.

“His work ethics were so strong that he imbued me with that spirit,” Scully once mentioned to a Cincinnati radio station. “Get to the ballpark early. Check, check, recheck. Talk to players, managers constantly.”

Scully would later say, “Nobody was going to get a big head working for Red Barber.”

As the sun sets on Scully’s broadcasting career, he will be long remembered for the steady tone of his voice along with his great knowledge of baseball. But his best attribute might be knowing when not to speak, such as following Kirk Gibson’s game-winning home run in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series. Scully and his partner, Joe Garagiola, let the scene at Dodger Stadium speak for itself for about a minute after the ball landed in the right-field bleachers.

To put it more succinctly, as the Chicago Tribune’s TV and radio columnist Anton Remenih wrote in 1953 regarding the World Series television coverage, Scully – and his partner, Mel Allen – knew just “when to shut up and let the camera talk.”

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum