- Home

- Our Stories

- Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

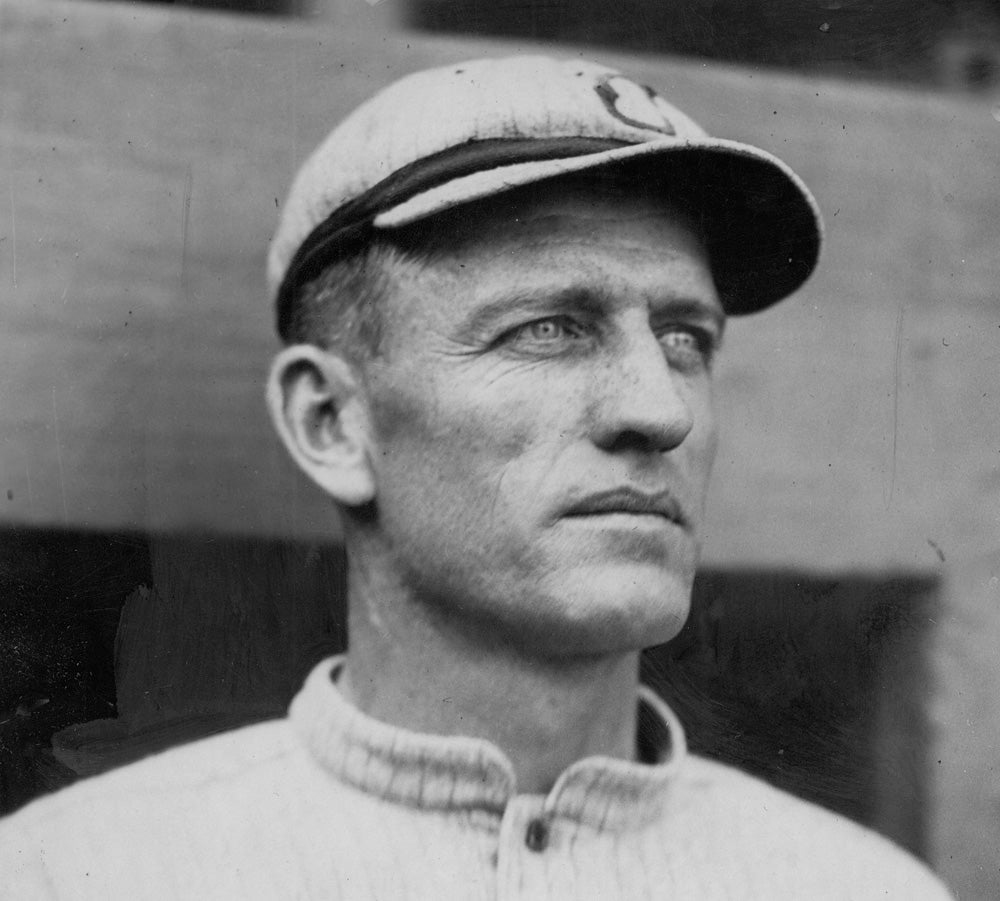

Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

In the early spring of 2015, after Derek Jeter retired, MLB.com ran a social media campaign to anoint the new “Face of Baseball.” It’s a relatively new concept that has been applied to players from Nomar Garciaparra to Mike Trout, and assigned retroactively to Jackie Robinson and Babe Ruth, among others.

But if there ever was a first “Face of Baseball,” it was Christy Mathewson.

Baseball in the beginning of the 20th century was considered an undignified game, played by ruffians for the pleasure of gamblers. In fact, many players did come from tough backgrounds, swinging out of coal mines and pitching out of farmlands to eke out a living at baseball. Few had college educations. Even fewer were seen as virtuous. Mothers (Mathewson’s included) did not want their sons to grow up to be baseball players.

Christy Mathewson changed all that. And the combination of his talent on the field and charisma off it helped him become one of the first five members of the Hall of Fame in 1936.

The Museum’s latest addition to the PASTIME online collection features the Class of 1936, including Mathewson.

The son of a farmer, Mathewson attended Bucknell University on scholarship for three years where he was an A student, class president, a member of literary societies, and a star on the football and baseball teams.

When Matty began his Major League career with the New York Giants in 1900, he had it worked into his contract that he wouldn’t pitch on Sundays (it was a promise he made to his mother and one he always kept), and he carried a Bible on the road. He was known for his honesty and integrity (one umpire said he would know if he got a call right if Mathewson confirmed it). He was bright; he excelled at bridge and checkers (he could play multiple games at a time, sometimes blindfolded, and once beat a national champion).

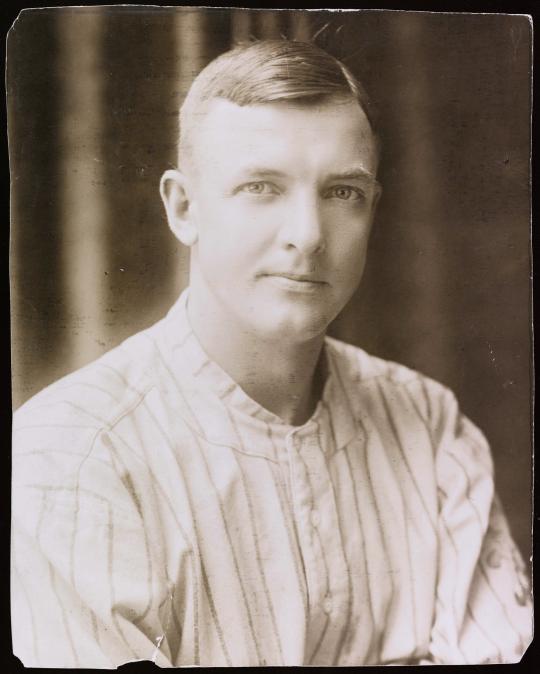

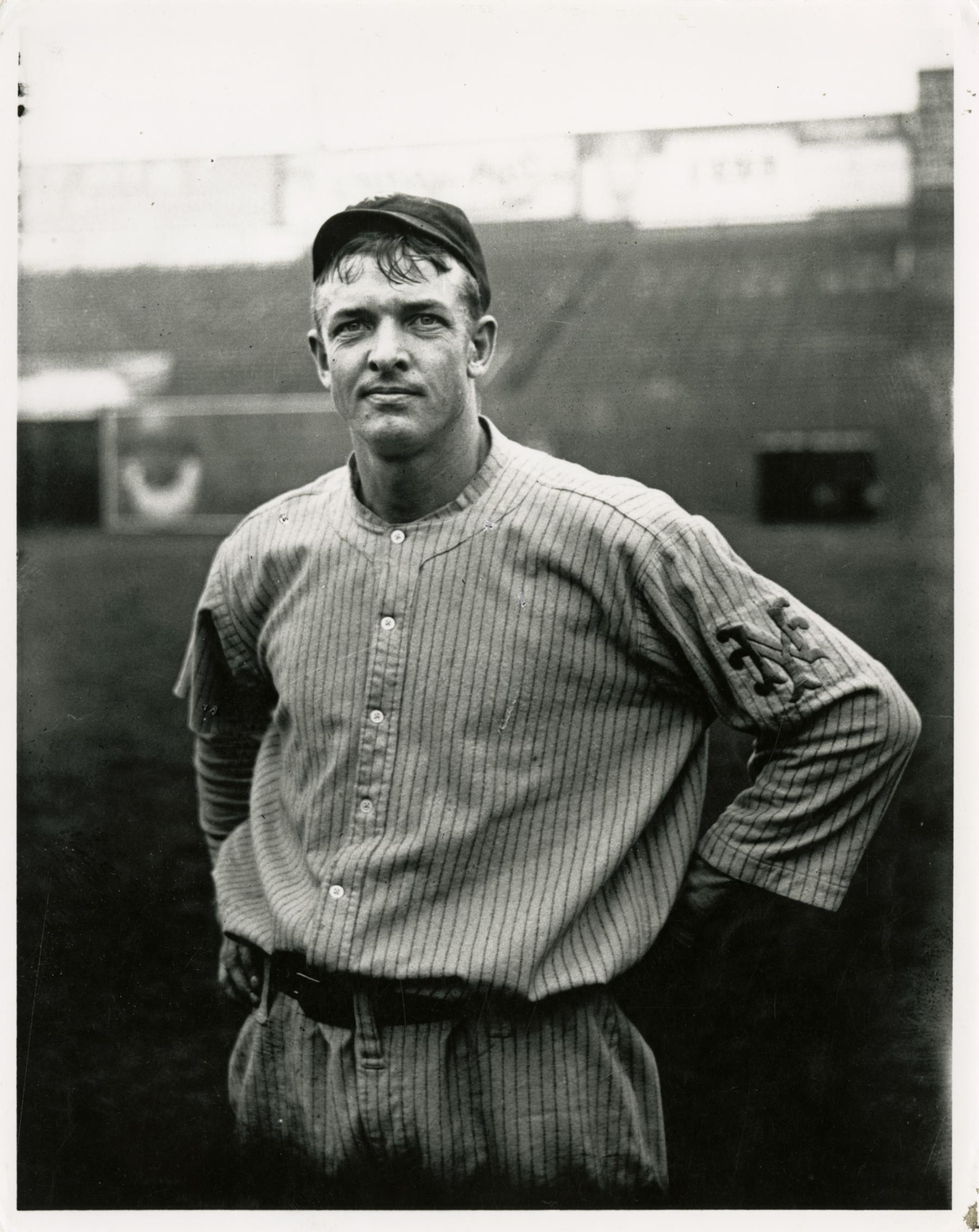

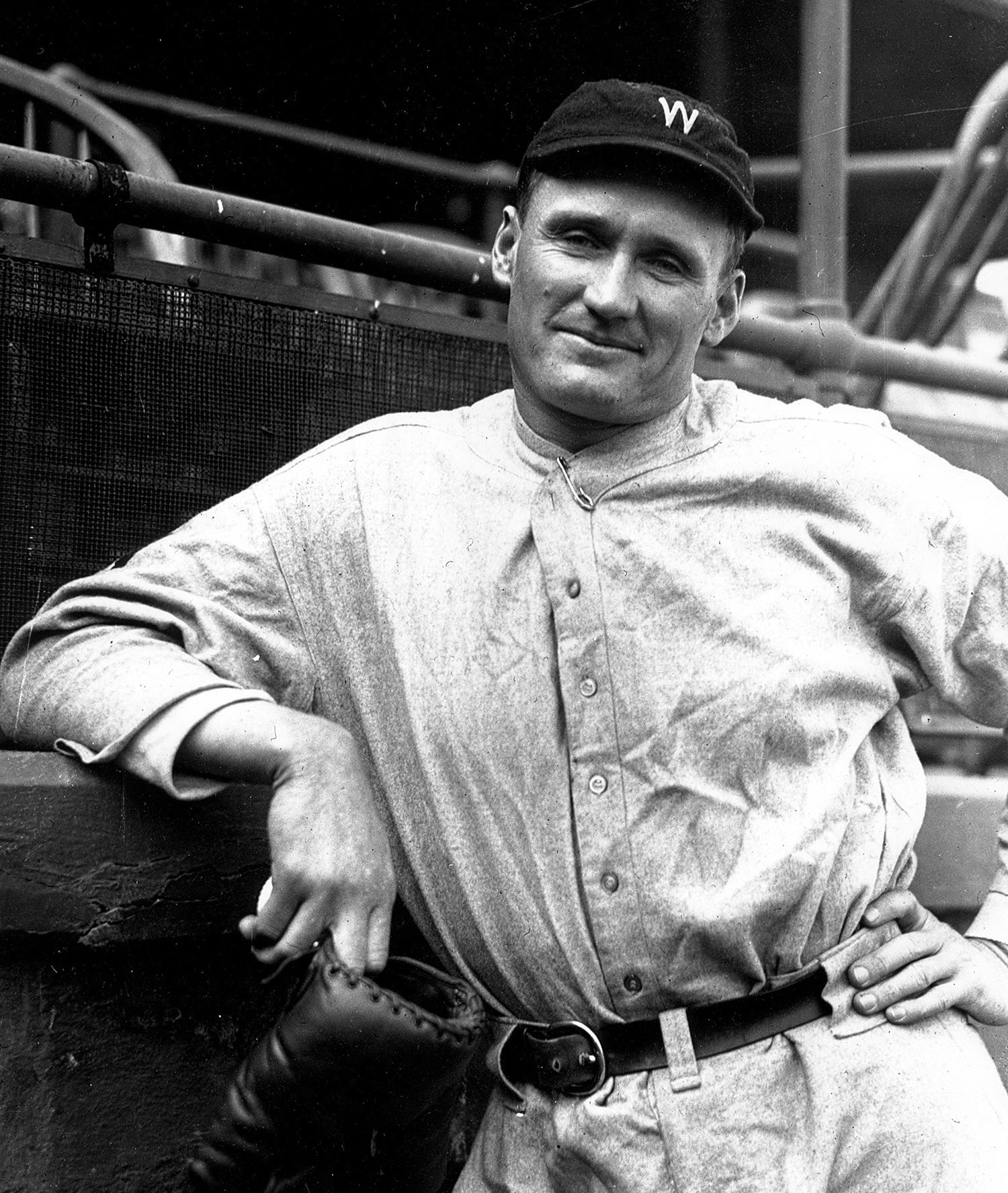

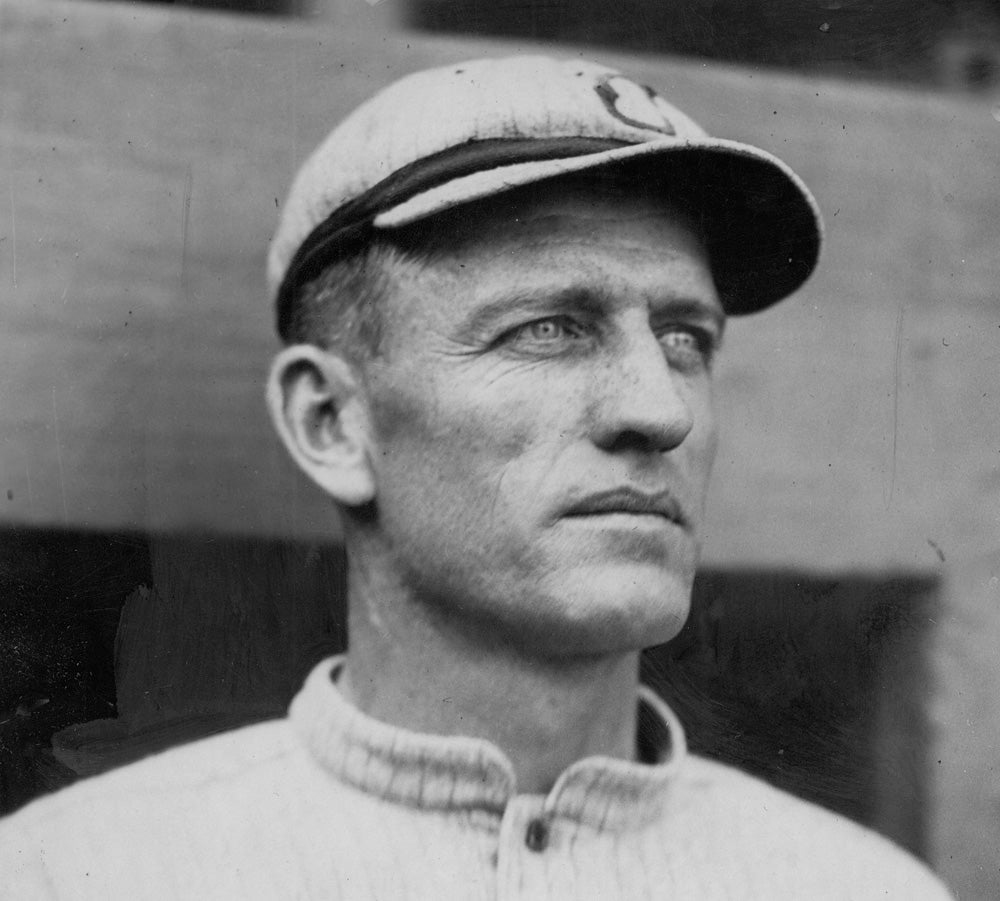

Then there was his physical presence. At 6-foot-1 and 195 pounds, with a strong jaw, slightly dimpled chin and kind, blue eyes, he made an immediate impression. “The sight of him was something,” teammate Larry Doyle recalled. “My heart stopped for a moment. Just looking at him, he affected you that way. He looked so big and sure and, well, sort of good. Like he meant well toward the whole world.”

John “Chief” Meyers added, “He had the sweetest, most gentle nature. Gentle in every way.”

To a game needing a role model, Christy Mathewson was manna from heaven. As wholesome as Matty may have been, the newspapers embellished it. They said he never swore, drank, or bet (though in fact he fleeced many teammates at cards). Grantland Rice said he “handed the game a certain touch of class, an indefinable lift in culture, brains and personality.” Another wrote that he “talks like a Harvard graduate, looks like an actor, acts like a businessman, and impresses you as an all-around gentleman.”

The irony to the myth-making and publicity was that Mathewson was a very private person. Celebrity held no real importance to him. He would draw the curtain when his train pulled into a station, and Doyle said Matty “hated” how everyone rushed to him with their questions, though he added that Mathewson “was always courteous.”

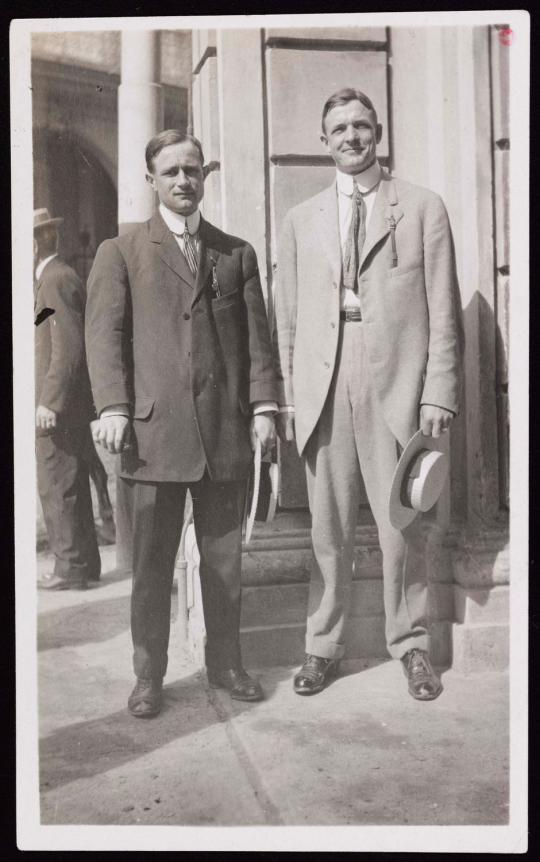

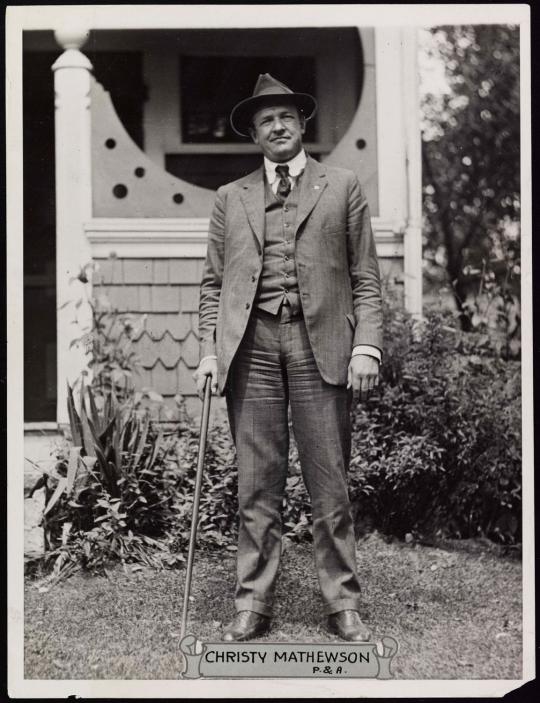

Mathewson had the gift of being able to accept what he couldn’t control, and he recognized he was the face of baseball. So even though he didn’t like having his photograph taken, he posed for the cameras.

And he smiled.

Most photographs of that age show ball players with stern or inexpressive faces. Longer exposures required a still face, and it’s easier to hold no expression at all than a smile. But Matty smiled.

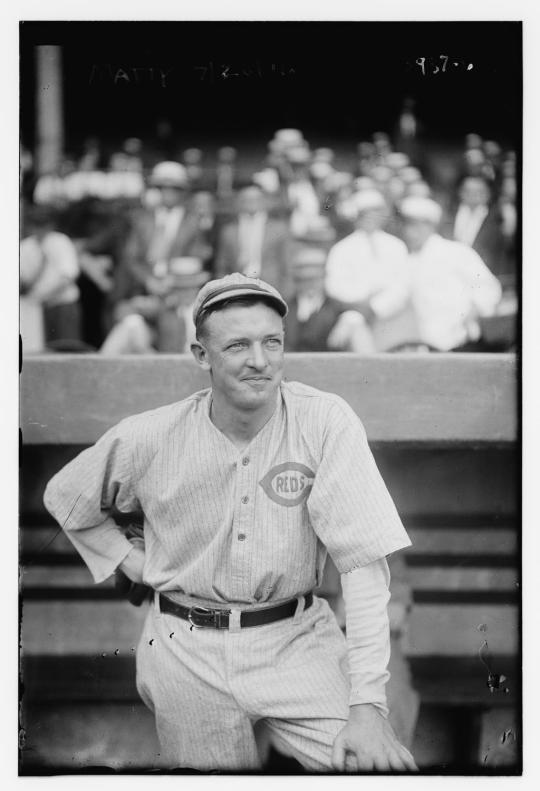

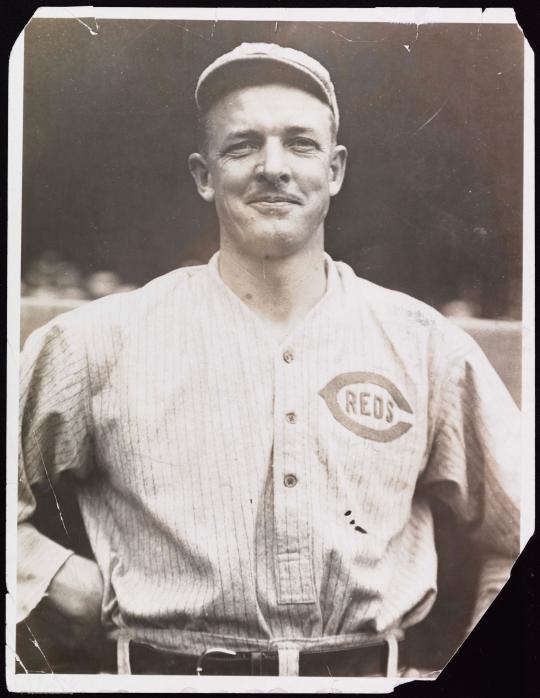

Looking through photos of Mathewson, one is struck by that smile, almost always the same: Mouth closed, lips pulled back, smile lines defining his cheeks. The right side of his mouth goes up just a little higher than the left. He squares up to the camera and looks directly into the lens. It’s a smile brimming with confidence, but not the least bit arrogant, one that welcomes, assures, puts one at ease.

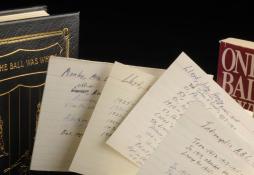

Charles Conlon, photographer of many classic baseball images from the first half of the 20th century, took his very first baseball portrait of Christy Mathewson. Over the years, Matty became Conlon’s favorite subject and a friend. He recalled that once day he saw Mathewson from across the field. It was after practice on a hot afternoon, and Mathewson was sweaty and tired. But he knew Matty wouldn’t say no. The resulting image – with his smile maybe not quite as pronounced as usual – is one of the most iconic portraits in baseball history.

In January of 1909, Mathewson’s younger brother, Nicholas, after completing his first semester of college (and possibly having been diagnosed with tuberculosis), went into the family barn and shot himself. Christy, who was home visiting his family, found the body. Mathewson never spoke of it to any reporter…nor of another brother, Henry, who died of tuberculosis at 30. These tragedies, for Mathewson, were private. For the public, he smiled.

He won the 1905 World Series almost single-handedly: Three complete game shutouts, giving up 13 hits and one walk in 27 innings, with 18 strikeouts. But Mathewson’s Giants lost the World Series in 1911, 1912, and 1913. No one blamed Mathewson (who went 2-5 in those Series, in spite of a 1.33 ERA); in fact, his sportsmanship was lauded. One editorial read, “In victory he was admirable, but in defeat he was magnificent.” Mathewson himself said, “You can learn little from victory. You can learn everything from defeat.” The losses ate at the highly competitive Mathewson, but he smiled.

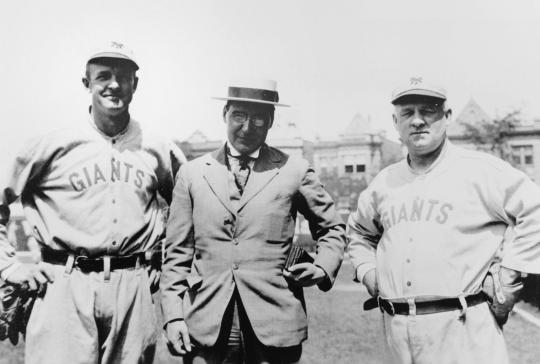

From 1901-1914, across 14 seasons, only once did Mathewson record fewer than 20 wins; four times he won at least 30 games. But in 1915, he struggled, with his worst ERA in a full season, and lost 14 of 22 decisions. The next year, in mid-season, struggling again and the Giants below .500, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds. He had spent 17 years with the Giants, and though he was part of the negotiations and understood he would be getting a chance to manage the Reds, the trade had to have been bittersweet. “Why, it’s alright,” he said. “It’s a step upward, you know.” His first day in Cincinnati, Mathewson dressed in his new uniform, went out onto the field, and smiled for the photographers.

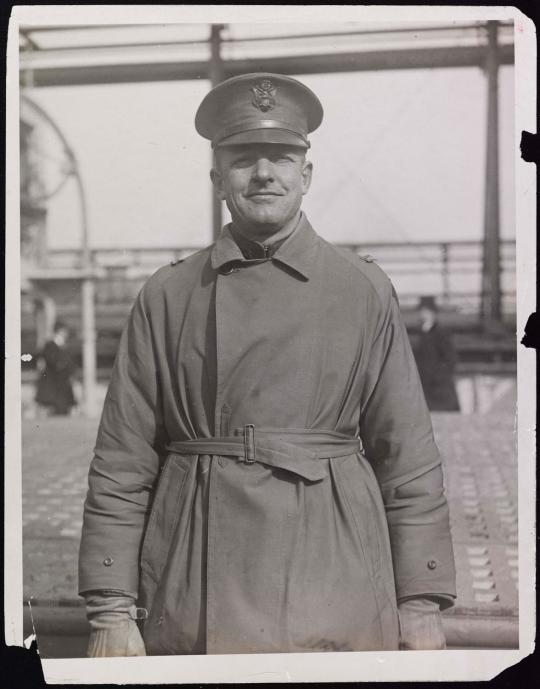

In 1918, Mathewson was 38 years old and exempt from military service, but he enlisted anyway. He caught the devastating 1918 influenza on the ship to Europe and had to be hospitalized for 10 days. Then he served in the Chemical Service department, teaching soldiers how to put on gas masks in dangerous trials. Ty Cobb, who served with him, said an accident once exposed Mathewson to nearly lethal amounts of mustard gas, damaging his lungs. In fact, when the armistice came, Mathewson was in the hospital again.

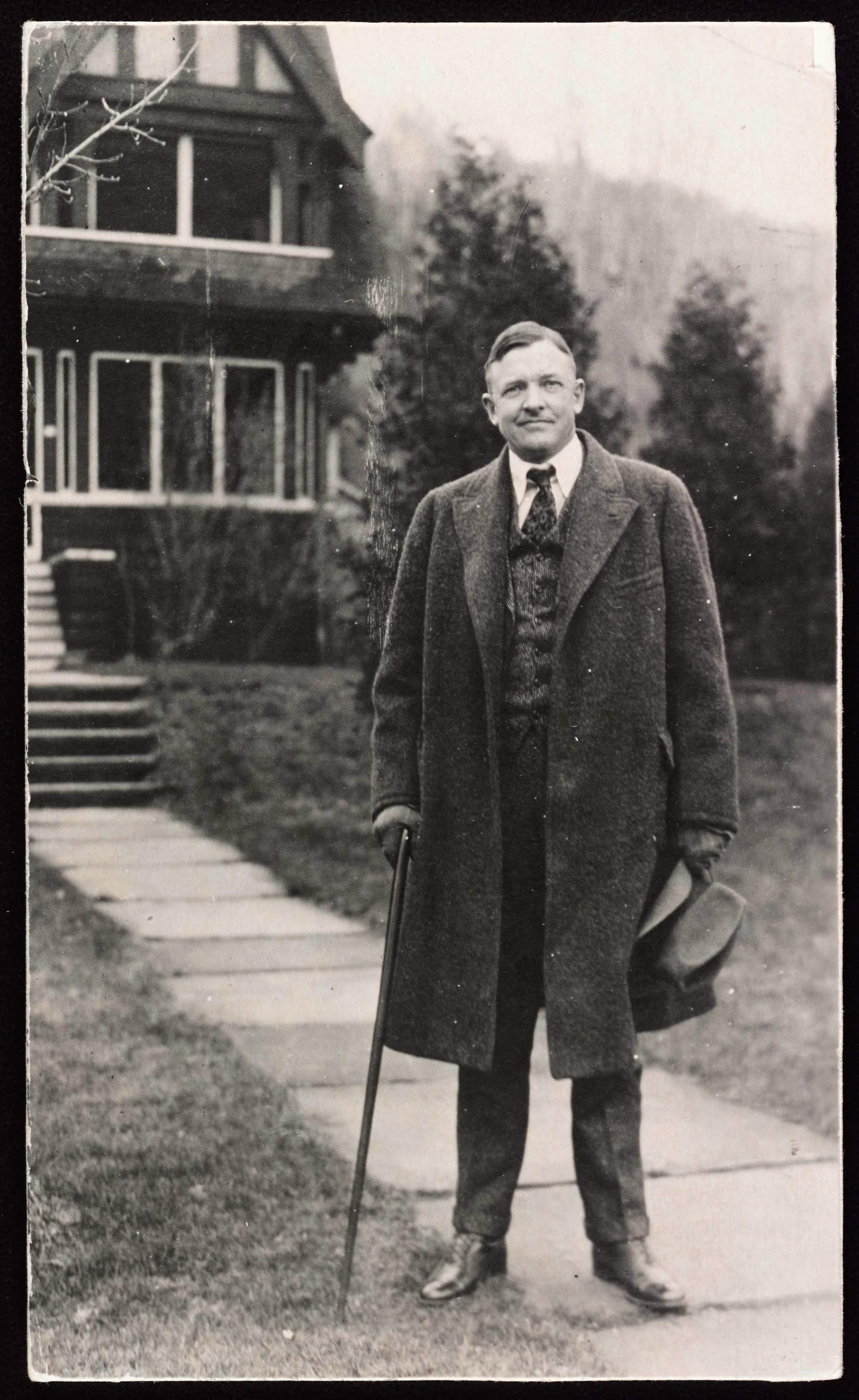

When he returned home, he still fought a painful cough. He also found out the Reds no longer had a job for him. When he was asked to pose for a photograph, he squared up, closed his mouth and pulled his right lip up just slightly more than the left, looking directly into the lens.

He took a job coaching with the Giants, but the cough didn’t go away, and his side began to ache. In the beginning of July in 1920, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He went to a nationally renowned tuberculosis sanitarium at Saranac Lake, N.Y. The physicians who examined him said both lungs were infected, and he might have six weeks to live. He was given absolute bed rest.

Months passed before he was allowed to sit up, months more before he could stand. In early 1922, he was permitted to go outside and visit a local baseball game where he threw out a ceremonial pitch. The press wanted updates. “I try to keep cheerful, keep my mind busy, try not to worry and I don’t kick on decisions,” he reported, “either by a doctor or an umpire.” Reporters wanted photos. Mathewson was very reluctant. Just the same, he stood in front of his residence and pose, his lung deflated as part of his treatment, in considerable pain, leaning on a cane.

The healthier he became, the more anxious he was to return to baseball. Though his doctors considered his recovery nearly miraculous, they strongly advised against his return to the stressful life of baseball. Nevertheless, in 1923, he became part of a syndicate that bought the Boston Braves. He built a home in Saranac Lake. He continued to cough.

Down in Florida for spring training in 1925, he caught a cold that worsened quickly. He returned to Saranac. He fought for several more months, his body getting weaker, his pain getting worse, until he knew the time had come. He told his wife that it was over. “Go into the other room and have a good cry,” he said to her. “But don’t make it a long one. This can’t be helped.” He died later that week, on Oct. 7, 1925.

Earlier, while recovering at Saranac Lake, he had played catch with some boys. A reporter asked if he had any advice for them. He stopped his throwing and said they should play baseball and learn from it. Then he ended with six words that epitomize his own character: “Be humble and gentle and kind.”

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visit www.baseballhall.org/DAP

More #Shortstops

A Glimpse of Moonlight

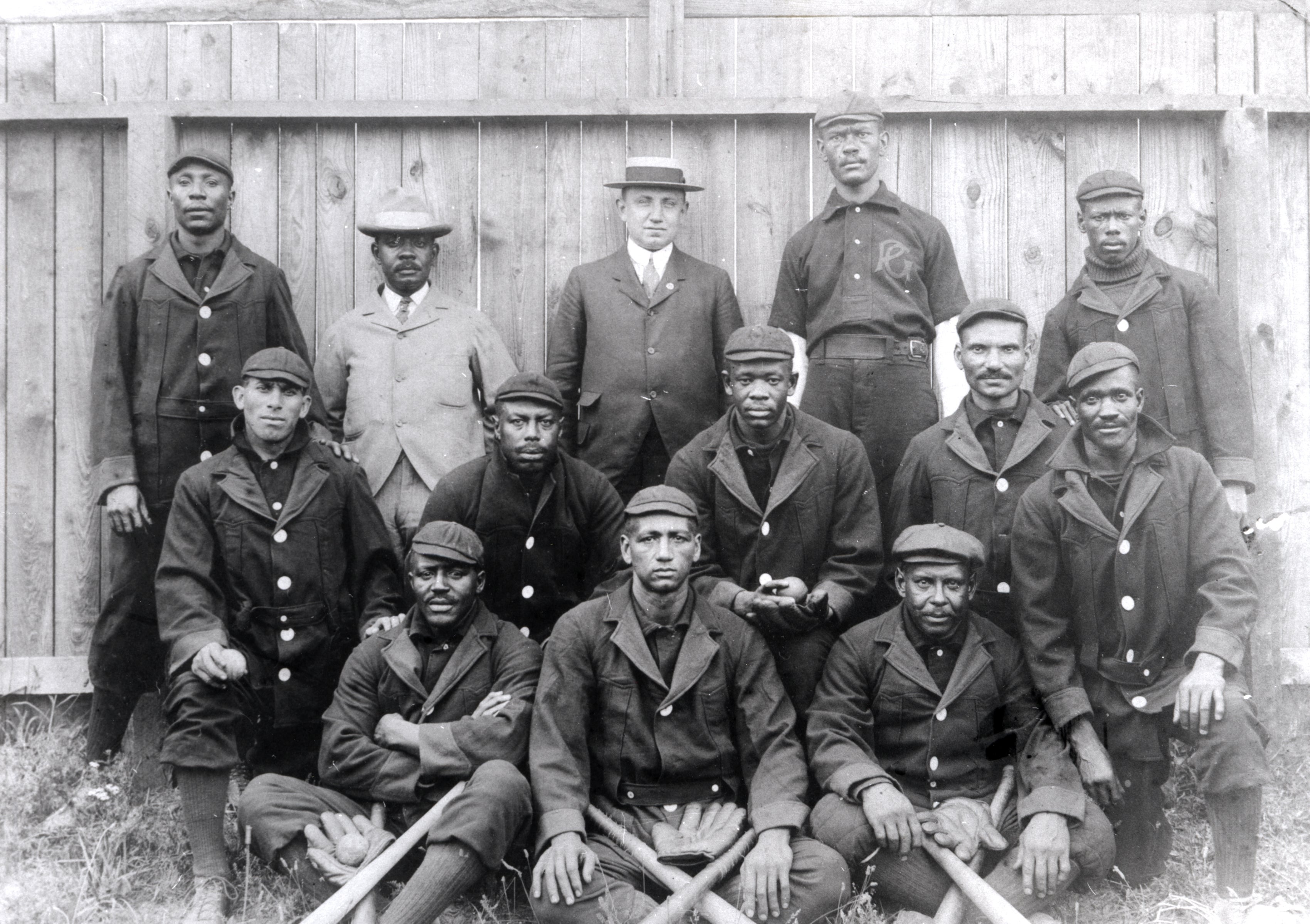

The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

Sol White helped change the face of baseball

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

A Glimpse of Moonlight

The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

Sol White helped change the face of baseball

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

Related Stories

Doc Adams helped shape baseball’s earliest days

1986 Hall of Fame Game

Film Fest a hit for fans, filmmakers

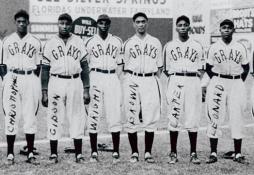

Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson are elected to the Hall of Fame

The Hall of Fame Remembers Jim Bunning

Tom Glavine joins 300-win club