- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball, boxing intersected famously at Forbes Field in 1941

Baseball, boxing intersected famously at Forbes Field in 1941

On a night more than eight decades ago, an unprecedented Steel City double-bill at venerable Forbes Field featured the unlikely pairing of a nondescript regular season baseball game and a championship boxing match.

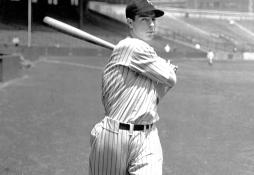

In 1941, a year that many consider baseball’s best with Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and the .406 batting average of Ted Williams, a midseason battle took place between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the visiting New York Giants, a pair of underperforming clubs that would finish the season with losing records.

Pirates Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

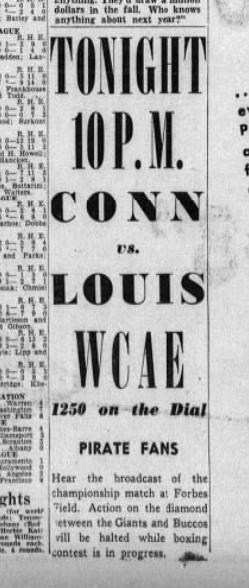

But this contest’s uniqueness came midgame – coming before televisions and transistor radios – when action was put on hold for an hour when fans were presented with a Mutual Broadcasting System radio call through the public address system from local station WCAE of a boxing match being held in New York City between heavyweight champion Joe Louis and local hero Billy Conn.

Unlike the famous line used by standup comedian Rodney Dangerfield – “I went to a fight the other night, and a hockey game broke out” – these Pittsburgh sports fans went to a baseball game interrupted by a fight.

The Pirates’ unconventional route was due to Conn, the light heavyweight champ from 1939 to ’41, who was born and raised in Pittsburgh. If they wanted anybody at all at their ballgame on Wednesday, June 18, 1941 – the first of seven night games the franchise hosted that year – they’d need an out-of-the-ordinary solution.

Their remedy? The baseball club announced that loudspeakers would be hooked up at Forbes Field and that as soon as the fight began, the ballgame would stop and be resumed again at the conclusion of the heavyweight bout. At the same time, WWSW, which aired the Pirates games, would have a musical interlude during the fight.

For a Pirates team with a total attendance of 482,241 in 1941 – averaging a little more than 6,000 per home game – attracting fans was imperative. The prior game, an afternoon affair with the Giants on June 17, drew only 1,586 despite featuring future Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell on the mound for New York.

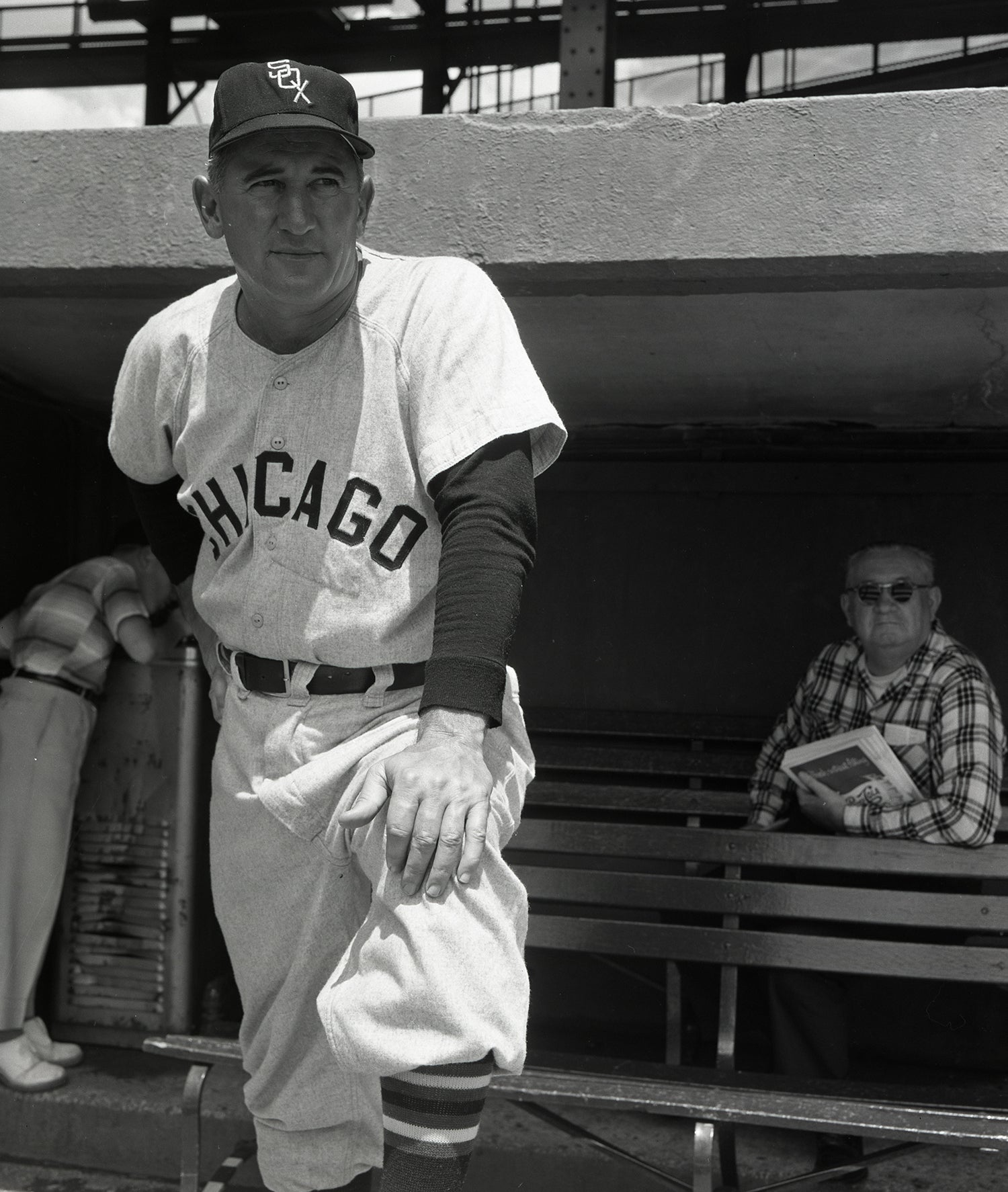

The three-game series between these two longtime National League squads included other future Hall of Famers besides Hubbell such as Pirates shortstop Arky Vaughan, catcher Al López, coach Honus Wagner and manager Frankie Frisch; Giants outfielder Mel Ott, catcher Gabby Hartnett and manager Bill Terry, as well as umpire Jocko Conlan.

Six months before Japan attacks Pearl Harbor, and less than three weeks after the tragic passing of Lou Gehrig at the age of 37, what has been called the “Fight of the Century” was set to take place at the Polo Grounds – the home ballpark of the New York Giants – around 10 p.m. EST.

Back in Pittsburgh, the gates to Forbes Field opened at 6:30 p.m., with the start of the game expected for 9:15 p.m. With night baseball still in its infancy – the Reds famously hosting the National League’s first night game in 1935 – most night games during this era began at this late hour reportedly because teams didn’t realize it was possible to play baseball in twilight with the lights on and thus waited until dark to play.

Popular local musician Dan Nirella and his band began a serenade soon after the gates opened and played familiar tunes of the time throughout the twilight period right up to gametime.

With an attendance of 24,738 – the highest single-game figure all season at Forbes Field – the lights were switched on at 9 p.m. Arguably the most anticipated “doubleheader” in Pittsburgh sports history began when home plate umpire Jocko Conlan gave the “Play ball!” command at 9:22 p.m.

The Pirates got off to a fast start thanks to a two-run triple by Bob Elliott off Johnny Wittig in the bottom of the first inning, only to see the Giants tie it up off Max Butcher with a solo home run from Ott – his 17th of the season – into the right field stands in the second and an RBI single by Joe Orengo in the fourth.

The ballgame was interrupted after 3½ innings, around 10 p.m. EST, in order that the blow-by-blow description from the radio broadcast of the world heavyweight championship fight in New York might be heard by the Pittsburgh faithful. The tower lights were turned off, the assembled crowd settled back to listen and the players either lingered in the dugouts or in the clubhouses.

To the dismay of those Conn fans in the stands, their local champion’s gallant effort – leading on points through 12 rounds – was dashed with a 13th round knockout by Louis. With 54,487 fight fans on hand, the 23-year-old “Pittsburgh Kid” entered the bout under cloudy skies at the Polo Grounds a prohibitive underdog, weighing 174 pounds compared the “Brown Bomber’s” 199½.

Conn, referred to by one newspaper as “the handsome, curly haired Irish kid from Pittsburgh,” came into the fight with a 59-9-1 record, while Louis, 27, was 49-1 – the lone loss a 12th round knockout by Max Schmeling on June 19, 1936. Conn was Louis’ 18th victim since he captured the heavyweight crown against Jim Braddock in June 1937.

Reports said the fans cheered when Conn was doing well, but a hush settled over Forbes Field when the fight ended at 2:58 of the 13th round. Fans could hardly believe it.

Asked why he decided to slug it out with Louis in the 13th round, Conn said, “I guess it’s the Irish in me. I knew I hurt him and had him going in the 12th round and was going out for a knockout, but he got to me first.

“All they say about his hitting is true. His punches feel like the kick of a mule, and they really hurt when they land.”

Louis’ explanation for his victory: “I knew I was behind when I went out in the 13th and had to go after him or lose my title. I was just hoping he would mix it with me some more, because if I stung him, I knew he would fight back. He did, and I finally caught up with him.”

The baseball game between the Pirates and Giants, with the hometown fans still buzzing after the near Conn triumph, returned in the second half of the fourth inning after a 56-minute interruption. With the need for pitchers to warm up, the action began again at 11:18 p.m. With all the scoring achieved prior to the interruption for the fight broadcast, the game finally had to be called at the end of the 11th inning with the score tied at 2-2. Despite the hour’s break for the brawl, Pittsburgh righty Max Butcher pitched all 11 innings. Play had to be called because of a major league rule which prohibited the starting of an inning after 11:50 p.m.

“I wonder,” Giants manager Bill Terry asked testily after the game, “what they’ll think up to break in on our night game with the Cardinals in St. Louis on Friday?” When a writer jokingly replied, “Maybe the Bob Hope program,” Terry muttered, “It wouldn’t surprise me in the least.”

In an interesting baseball side note to the whole story, news of the heavyweight title bout was interrupted the day before the fight by the news that Conn was engaged to 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith, the daughter of Greenfield Jimmy Smith, a former utility infielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Giants, Boston Braves, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies for six seasons between 1916 and ’22 after a pair of years in the Federal League with Baltimore and Chicago.

While Conn admitted he was to marry Mary Louise Smith, he denied rumors that he they had already wed.

“But, what the devil,” said Conn. “I’m gonna get my head beat in anyway by her father. He’s right fair with his dukes and he’s a wild-eyed Irishman – and you know, and Louise’ll know, what a wild-eyed Irishman can do.”

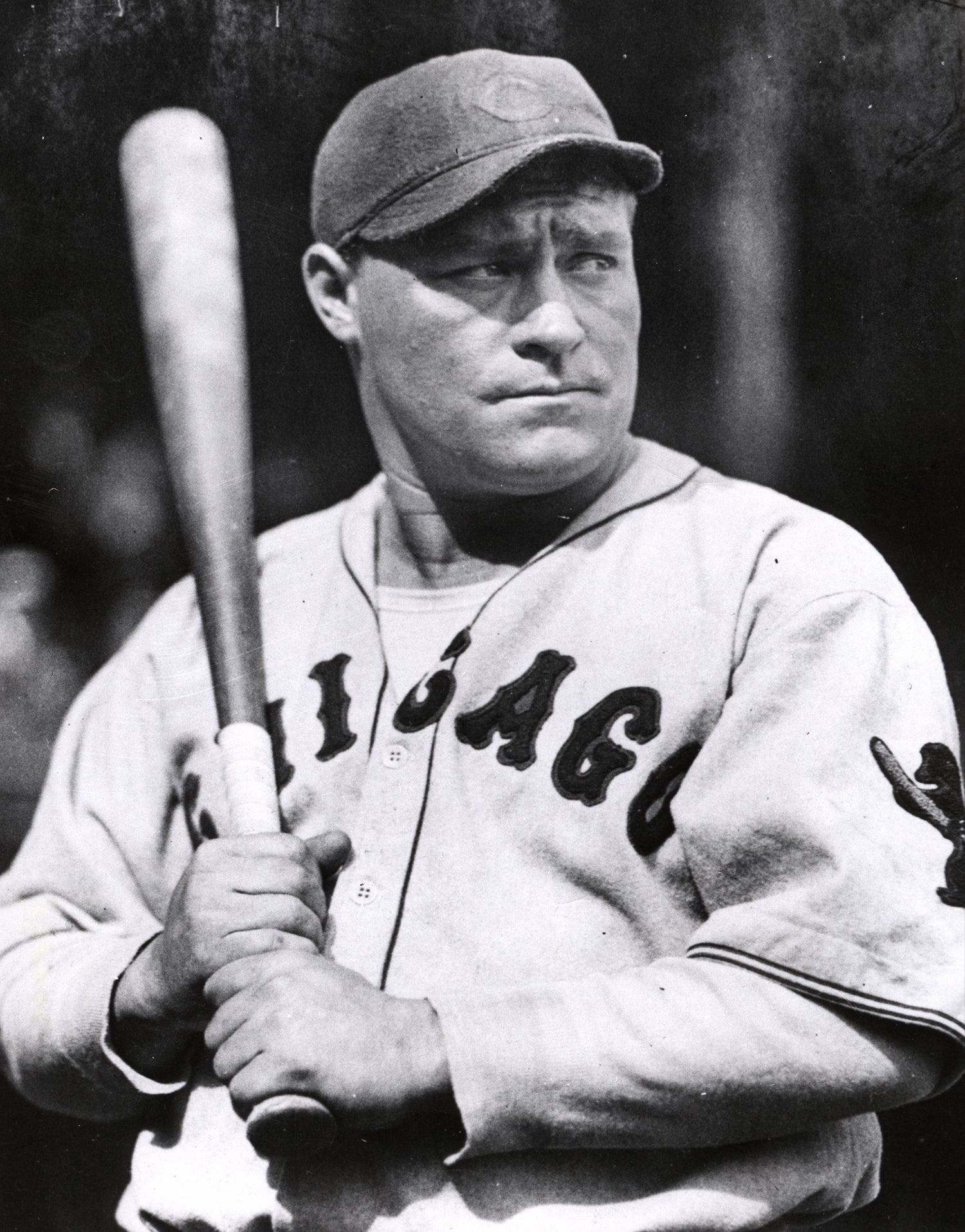

This news did not go over well with Louise’s dad, a pugnacious 5-foot-9 former ballplayer renowned for his bench jockeying and reputation for his use of fists both on and off the field.

After being made aware that the young couple had recently applied for a marriage license in Pennsylvania days prior to the Louis fight, Jimmy Smith didn’t mince words, voicing violent objections to the potential wedding.

“Champion or no champion, I’ll punch hell out of that fellow and he’d probably be the first one to say I could do it,” Smith said. “I hope he wins, but I want him to stay away from my family. I’m trying to raise a decent family (he had two boys and two girls), and I don’t want any of my children mixed up with prizefighters.

“My daughter has just turned 18 and at her age I wouldn’t want her to have anything to do with (even) the greatest fellow in the world.”

At the time, 21 was the minimum age a woman could get married in Pennsylvania without parental consent.

After a proposed wedding date on June 20 – two days after the Louis fight – was postponed because of parental objections and rules of the Catholic church, the pair who had been dating for four years were married at St. Patrick’s church in Philadelphia.

According to Conn, “the old man” had not given the pair his blessing and “he’s pretty sore.”

Informed of the marriage by phone at his home, Conn relayed what his father-in-law said: “I’m still against it and I always will be.”

When Conn’s firstborn, Timmy, was christened in May 1942, the boy’s godfather, Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney, attempted a reconciliation between the warring parties at the christening party. Instead, a fight between Jimmy Smith and Conn broke out.

What took place is described in a famous Frank Deford piece in the June 17, 1985, issue of Sports Illustrated titled, “The Boxer and the Blonde.”

“On Sunday, at the party, Greenfield Jimmy and Conn were in the kitchen with some of the other guests,” Deford wrote. “That is where people often congregated in those days, the kitchen. Billy was sitting up on the stove, his legs dangling, when it started. ‘My father liked to argue,’ Mary Louise says, ‘but you can't drag Billy into an argument.’ Greenfield Jimmy gave it his best, though. Art Rooney says, ‘He was always the boss, telling people what to do, giving orders.’ On this occasion he chose to start telling Conn that if he were going to be married to his daughter and be the father of his grandson, he damn sight better attend church more regularly. Then, for good measure, he also told Billy he could beat him up. Finally, Greenfield Jimmy said too much.

“’I can still see Billy come off that stove,’” Rooney says.

“Just because it was family, Billy didn't hold back. He went after his father-in-law with his best, a left hook, but he was mad, he had his Irish up, and the little guy ducked like he was getting away from a brushback pitch, and Conn caught him square on the top of his skull. As soon as he did it, Billy knew he had broken his hand. He had hurt himself worse against his own father-in-law than he ever had against any bona fide professional in the prize ring.”

Conn’s injuries from the fight with Smith delayed a rematch with Louis until June 19, 1946, the “Brown Bomber” knocking out his opponent in the eighth round.

As for “The Boxer and the Blonde,” they remained married until Billy’s death at the age of 75 in 1993. Mary Louise passed away at 94 in 2017.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum