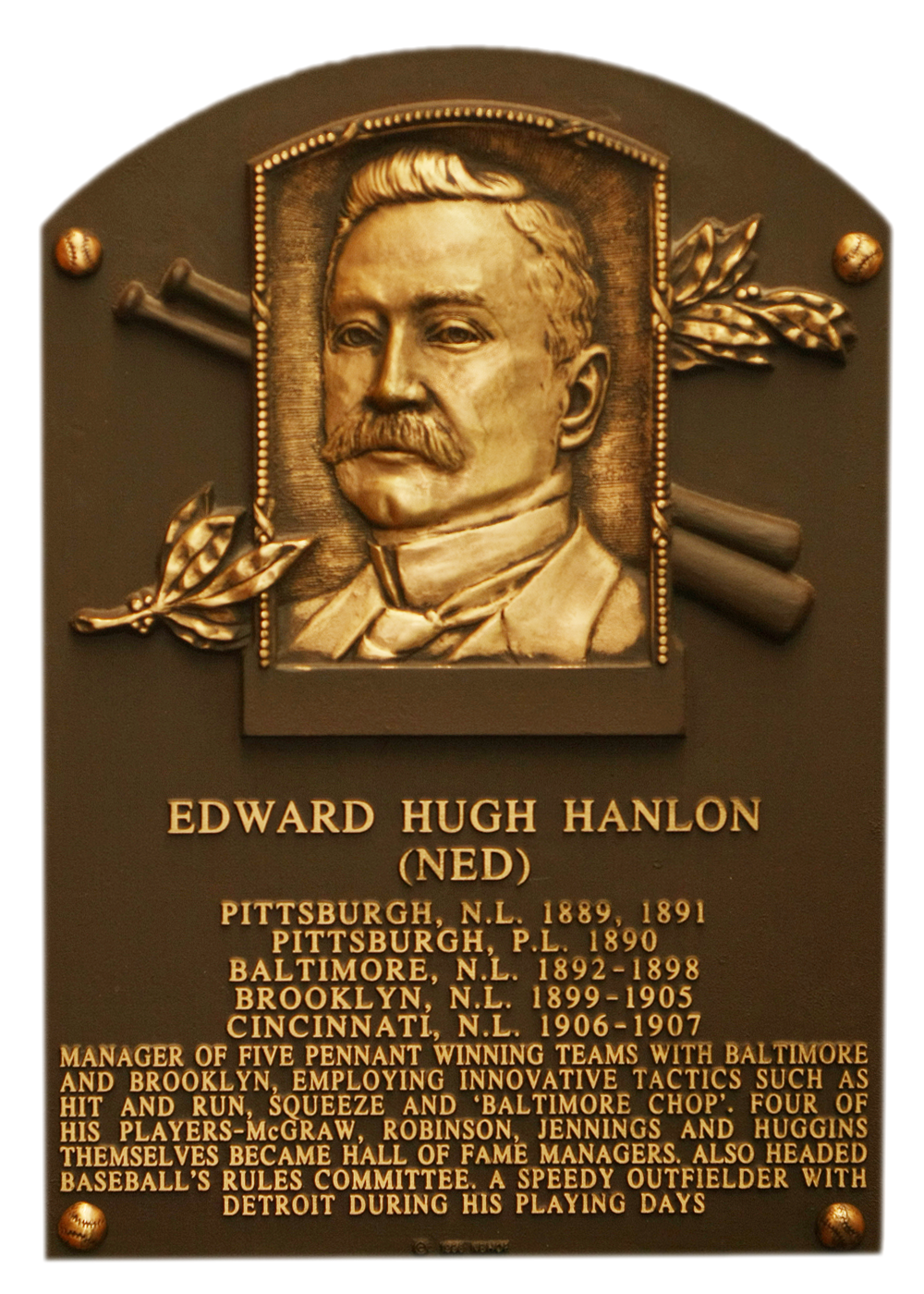

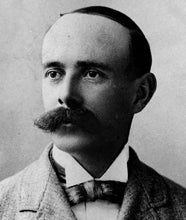

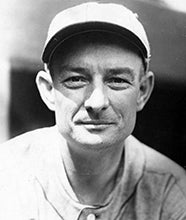

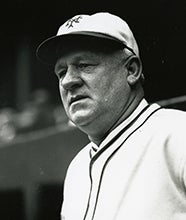

Long before the term “small ball” became popular, manager Ned Hanlon was among the first to recognize that a team could generate just as many runs with its legs as it could with its bats.

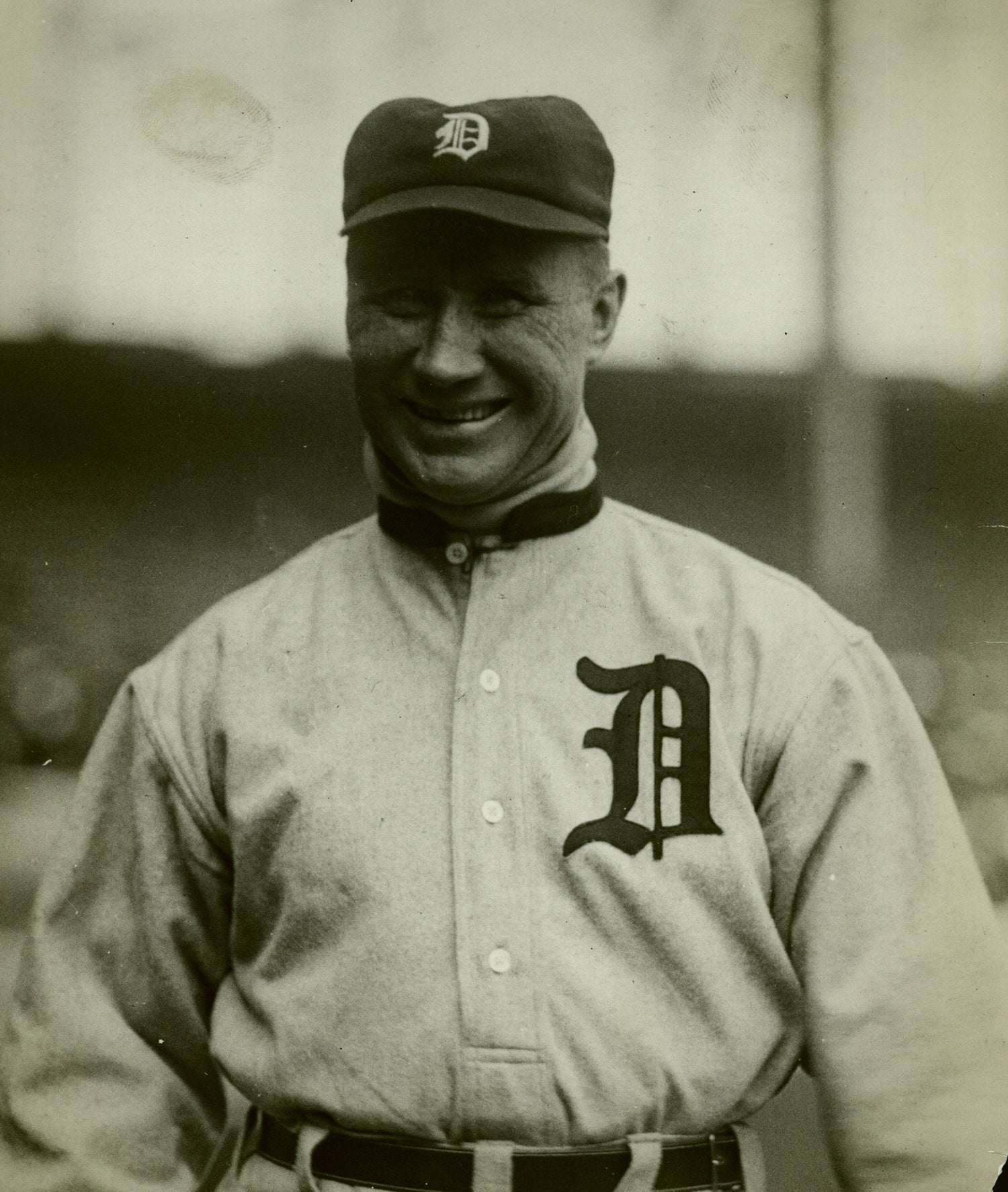

Hanlon began as a fine outfielder in 13 professional seasons in Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Baltimore. Though he was a career .260 hitter, Hanlon stole 329 bases – all of them coming after stolen bases were first recorded in 1886, six years into his career.

“It is a striking illustration of Ned Hanlon's daring and speed that for two years Buck Ewing has never once succeeded in throwing him out at second on a steal,” wrote The Sporting Life. “And Buck is one of the best throwers in the League.”

Hanlon was also revered as one of the game’s best outfielders, topping the National League in putouts in 1882 and 1884. As captain of the Detroit Wolverines, Hanlon led the club to its only pennant in 1887.

After traveling with A.G. Spalding’s famous “Around The World Baseball Tour” in the winter of 1888, Hanlon became player-manager of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in the second half of 1889. The following season, Hanlon placed his full support in the burgeoning Players’ League, which sought to break away from the National League and its owners’ reserve clause. Hanlon posted one of his best seasons with a sterling .383 on-base percentage, but the league folded after just one season.

“I want to say, gentlemen, that you can talk of the loyalty of a Ward, a Ewing, a Keefe and so on, but give me Ned Hanlon above everybody else,” said league organizer Albert Johnson. “He stands to-day as the hero of the Players’ League. He is the only ball player in that League who has held to the contract he signed. Not a penny has he received for his work this season, although he has played better ball than ever before.”

Hanlon returned to the Alleghenys for one more season, where he would unintentionally alter the franchise’s identity. After he traveled to Pennsylvania's Presque Isle Peninsula to sign second baseman Louis Bierbauer away from Philadelphia, Hanlon’s tactics were deemed “piratical” by an American Association executive. The insult stuck, and the Alleghenys would be known as the Pittsburgh Pirates forever more.

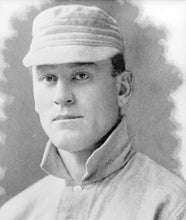

Hanlon spent one more year as a player in Pittsburgh before taking over the NL’s Baltimore Orioles club in 1892. It was near the Inner Harbor where Hanlon made his permanent stamp on the game, transforming the Orioles from cellar dwellers to perennial powers. Armed with a core of feisty players that included future Hall of Fame managers Hughie Jennings and John McGraw, Hanlon developed a set of rough, aggressive strategies that would be copied by many teams during the Deadball Era.

Known as “Inside Baseball,” Hanlon’s philosophy centered on teamwork, speed and execution. He incorporated baseball’s first regular use of plays like the hit-and-run, the sacrifice bunt, the suicide squeeze and the double steal. Hanlon also developed the famous “Baltimore Chop,” in which players like McGraw would pound a pitch directly into the ground and sprint to first while the ball bounced high above home plate.

Perhaps drawing on his own mixed success as a hitter, Hanlon was among the first to employ a platoon system that alternated players in and out of the lineup depending upon whether the pitcher was right- or left-handed.

"It occurred to [Hanlon] that a run gained by strategy counted as big as a run gained by slugging,” wrote The Baltimore Sun. “Accordingly, he evolved an offensive technique that made baseball into something of an art."

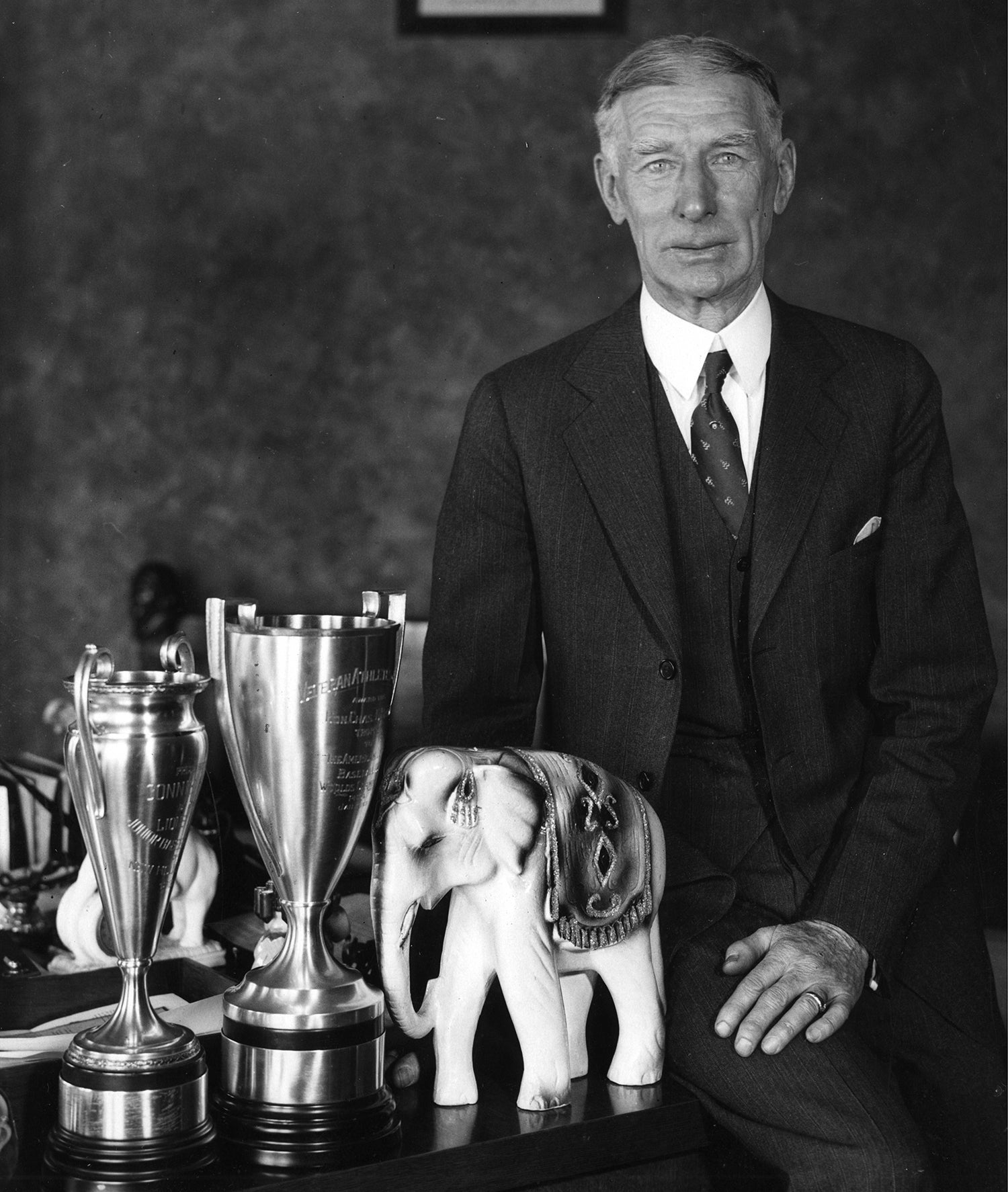

From 1894-1900, Hanlon captured five out of seven NL pennants with Baltimore and Brooklyn, making him professional baseball’s most successful manager since Harry Wright.

“I always rated Ned Hanlon as the greatest leader baseball ever had,” said Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack who played both for and against Hanlon in the 1890s. “I don't believe any man lived who knew as much baseball as he did.”

In 1937, the Sporting News deemed Hanlon to be the “game’s greatest strategist” and “The Father of Modern Baseball.”

Hanlon passed away on April 14, 1937. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1996.