- Home

- Our Stories

- Negro Leagues Committee members reflect on the historic 2006 election

Negro Leagues Committee members reflect on the historic 2006 election

In 2006, a total of 17 accomplished ballplayers and executives who went largely unnoticed simply because of their dark skin were recognized with the sport’s greatest honor.

This oft-forgotten chapter in the National Pastime’s history came to the forefront recently thanks to a announcement this past December when Major League Baseball officially recognized the Negro Leagues with “Major League” status. This allowed the approximately 3,400 players that saw action between 1920 and 1948 to be remembered as major leaguers.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

While baseball segregation held sway in the decades prior to Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in 1947, Black baseball continued to produce legendary figures.

On Feb. 27, 2006, it was announced that 17 individuals from the Negro Leagues and pre-Negro leagues were elected by a special committee to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

A committee of 12 Black baseball scholars and historians met in Tampa, Fla., to discuss and vote on each candidate on a ballot consisting of 39 names. The final ballot was pared down from a roster of 94 by a five-member screening committee in late 2005.

The election results featured 12 players and five executives – each having received the necessary 75 percent vote from committee members.

The electees included seven Negro Leagues players: Ray Brown, Willard Brown, Andy Cooper, Biz Mackey, Mule Suttles, Cristóbal Torriente and Jud Wilson; five pre-Negro Leagues players: Frank Grant, Pete Hill, José Méndez, Louis Santop and Ben Taylor; four Negro Leagues executives: Effa Manley, Alex Pompez, Cumberland Posey and J.L. Wilkinson; and one pre-Negro Leagues executive: Sol White.

“The Board of Directors is extremely pleased with how this project has evolved over the last five years – culminating in today’s vote,” said Hall of Fame Chairman Jane Forbes Clark at the time of the announcement. “Over the last two days, this committee has held discussions in great detail, utilizing the research and statistics now available to determine who deserves baseball’s highest honor – a plaque in the Hall of Fame Gallery in Cooperstown.”

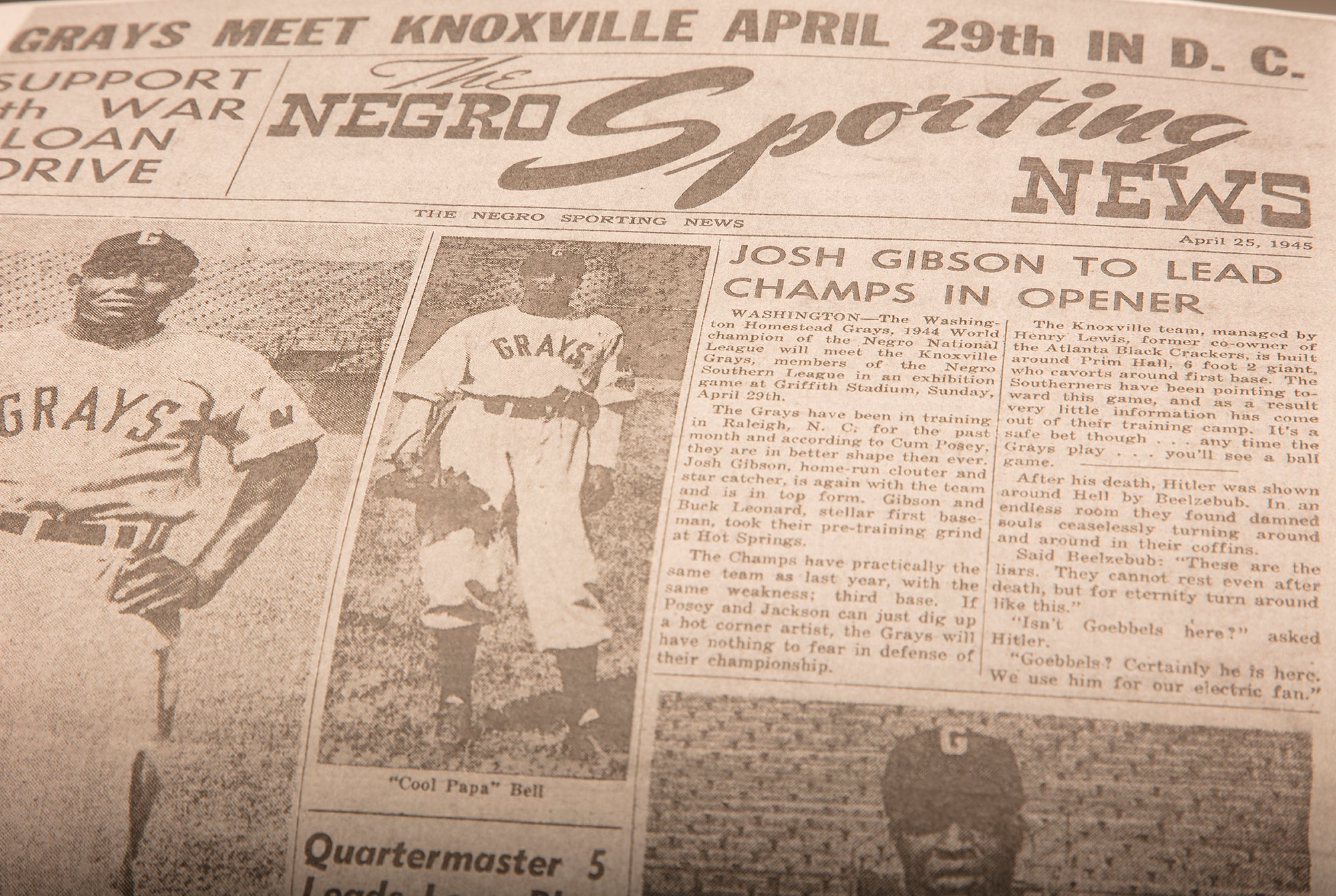

The 2006 electees joined 18 Hall of Famers elected for their Negro Leagues contributions already enshrined in Cooperstown: Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Martín Dihigo, Bill Foster, Rube Foster, Josh Gibson, Monte Irvin, Judy Johnson, Buck Leonard, Pop Lloyd, Satchel Paige, Joe Rogan, Hilton Smith, Turkey Stearnes, Willie Wells and Joe Williams.

Former MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent, a non-voting chairman of the committee, said at the time: “We were not here to rewrite American history, we were not here to do social good, we were here to elect individuals of high performance to the Hall of Fame.

“The whole history of this issue of race in our society is a topic that involves very bad timing. These people who were candidates were greatly honored by being candidates, I'm sure, but it would have been so much nicer had we been able to do this 30 or 40 years ago and have so many more alive.”

The election was the byproduct of a Baseball Hall of Fame receiving a $250,000 grant from MLB in 2000 for an in-depth study of Black baseball from 1860 to 1960. More than 50 authors, researchers and historians produced a first-of-its-kind academic study that resulted in a history and bibliography of more than 800 pages as well as a statistical database.

“On behalf of Major League Baseball, I applaud the National Baseball Hall of Fame for conducting this special election of former Negro League stars, and I heartily congratulate those who were elected,” said Bud Selig, the baseball commissioner at the time. “Major League Baseball is proud to have played a part in a process that has corrected some of those omissions.”

The 12-member voting committee, appointed by the Hall of Fame Board of Directors, included Todd Bolton, Greg Bond, Adrian Burgos, Dick Clark, Ray Doswell, Leslie Heaphy, Larry Hogan, Larry Lester, Sammy Miller, Jim Overmyer, Robert Peterson and Rob Ruck.

Adrian Burgos (left) shares a moment with Justino Clemente (center), Roberto Clemente's brother, and Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar during a 2018 visit to the Hall of Fame. Burgos was one of 12 electors who considered the groundbreaking 2006 Negro Leagues Hall of Fame ballot. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Peterson, author of the groundbreaking 1970 book, “Only the Ball Was White,” died in Feb. 11, 2006, casting his ballot two days prior to his passing.

In interviews with four members of the committee, all expressed what an honor it was to be asked to participate as well as the importance they placed on their votes.

“It was an awesome opportunity to be involved with something so historic without realizing the impact that it would have in changing the narrative about Negro baseball history,” said Lester, a Negro Leagues historian and author. “People still talk about it today. When you’re in the moment you don’t think about it. It’s like being in the World Series. You’ve earned the right to be there but sometimes it doesn’t dawn on you that you’re at the pinnacle of everything that you’ve been trying to accomplish.

“I researched Black baseball so I could learn more about men of color, people who look like me – nothing more than that. I never expected for it to become a cottage industry or a chapter in baseball history. I do it because I love doing it. Now people want to listen to my opinion about something that I love. That’s incredible.”

Heaphy, an associate professor of history at Kent State, called her participation “still one of the most important things that I’ve ever had a chance to be a part of.

“It was certainly an honor to be asked to participate, but I also felt it was a big responsibility, too. It was an important thing to do and I wanted to make sure we did justice to what we were asked to do,” she said. “This was such a big part of baseball history. And seeing men and women, in this case, being recognized for their accomplishments, that’s a responsibility.”

Burgos, a history professor at the University of Illinois, looked back with bittersweet memories on his time on the committee.

“After we had elected so many individuals, the two living candidates, Buck O’Neil and Minnie Miñoso, were not elected,” he said. “I remember very distinctly how it was that Raymond Doswell and I had been entrusted in putting the cases of Miñoso and O’Neil, respectively, before our colleagues on the committee. I still feel that Minnie Miñoso very much merited inclusion while he was alive and I hope that we will see the day when he is included posthumously.

“At that point being a young Latino professor, I also felt a responsibility of getting the story of the legacy of the Negro Leagues having a Latin American component. To have Cristobal Torriente, José Méndez and Alex Pompez part of the group elected was very important.”

The committee also received important counsel from Hall of Famer Frank Robinson.

“A couple of things really stand out about that weekend. One was the role that Fay Vincent, and to a lesser extent, Frank Robinson, played,” said Ruck, a professor of sport history at the University of Pittsburgh. “Vincent was just really perceptive and did an amazing job chairing those sessions. Given the number of people we were trying to discuss and how to resolve that within a couple of days, it’s pretty impressive. I’ve been in enough faculty meetings to know how often meetings go off the rails.

“One of the things that stood out about Fay and Frank was in their introductory remarks about Hall of Fame membership. It was really to consider integrity of the individuals. That has stayed with me. In my mind the significance of an individual and how that person conducted him or herself was critical – significant both on and off the field – because in many of these cases we had limited statistical data.”

“I remember listening to Frank Robinson when he called in,” said Heaphy, “to remind us of the importance of thinking about what the Hall of Fame stood for and not simply to put people in to put people in.”

“The meeting were run very professionally by Commissioner Fay Vincent,” Lester said. “And the groundwork laid by Frank Robinson on the front end of the two days, who said there were four categories and four categories only – with no humanitarian awards, no popularity contests – umpire, manager, player and owner.”

Whatever expectations or goals the committee members had prior to arriving in Tampa, in retrospect they agreed it played out well.

“We had a hearing on every single one of those 39 individuals on the ballot,” Burgos said. “Even if we saw it as a slam dunk case, someone stood there at the table and presented the strengths of the case or these may be some of the issues. We got to talk about every single one of those individuals. That was an important part of the process. Private ballots collected after each individual vote. And then we would move on to the next.”

Lester, stating his goal was to vote his conscience, adding: “I was confident that we’d maybe get six people into the Hall of Fame. When you’re looking at a three-fourth majority to get elected, that’s tough to come by. So when they announced 17 I was surprised and shocked. I was extremely happy with the results.

“The beauty of our committee was we had experts in different categories, so if there was a place I felt a weakness in I could throw that question out to the table and get an immediate answer.”

Heaphy, who said she entered the process “with an open mind,” added, “I really had no expectations. I just knew that this was an opportunity. And we would give each and every one of the candidates their due as we went through the list of candidates.

Ruck said: “Some of the choices were so clear cut that there wasn’t much of a need for extended discussion. Others we had records, but they were pretty incomplete. One of things that would happen would be people in that room could fill you in on them and point to their significance or point to things that might detract.

“You’re in a situation where you’re dealing with a lot of candidates. To a degree you’re trusting in the judgments from other people in the room.”

As the only woman on the committee, Heaphy did admit to a certain affinity for Manley and her ultimate election. Manley co-owned the New Jersey-based Newark Eagles with her husband, Abe, and ran the business end of the team for more than a decade.

“Being 100 percent honest, it was pretty incredible to see her name in that final group and recognizing that she was the first women ever to be elected to the Hall of Fame,” Heaphy said. “It still means a great deal. I just hope that one day she will no longer be the one and only. But to have a part in that and to hear that name was really incredible.”

Ruck, calling the study of Black baseball an “area that had been ignored and dismissed for a long time,” added: “But then there was a critical mass emerging of popular and scholarly recognition. Things are building. And I think that the 2006 vote should be seen in that context. I think MLB’s most recent decision should also be seen in this continuing evolution.

“I’ve been teaching about black baseball in my history of sport courses at Pitt since I’ve been a grad student in the late 1970s. At first hardly any kid had heard of these teams or players, but now most of them have.”

Bruce Sutter, the lone electee by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America that year, and the 17 electees from the Negro League and pre-Negro League eras made 2006 the largest single inductee class in history, breaking the record of 11 in 1946.

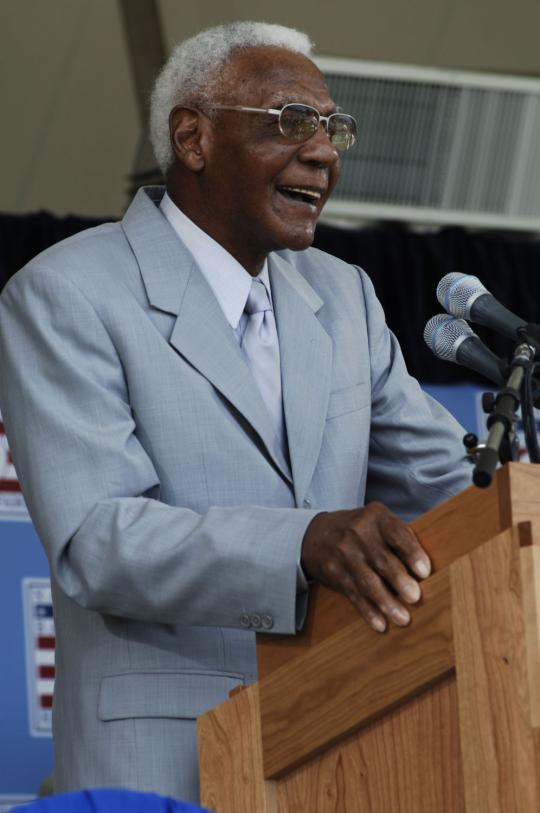

On July 30, 2006, the 18 members of the Hall of Fame Class of 2006 were inducted. The Sunday ceremony featured O’Neil, the former Negro league first baseman and at time the chairman of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, speaking to the crowd after a standing ovation.

“I've been a lot of places, I've done a lot of things that I really liked doing,” O’Neil said. “I hit the home run, I hit the grand slam home run, I hit for the cycle, I've hit a hole in one in golf. I've done a lot of things I like doing. But I'd rather be right here right now representing these people that helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum